A fond farewell to Raymond Beadle

|

|

ust last week, Insider reader Richard Pederson was reveling, with me, in the fact that last Friday’s column had been a joyous one, sharing great old photos instead of having to talk about another drag racing luminary who had passed away.

That feel-good moment lasted until 6 a.m. Monday, when I got a text from Richard Tharp. Honestly, I didn’t even have to read the text to know the news would not be good. Reports had been coming out of Dallas for the last month about the deteriorating condition of one of the sport’s all-time greats and grew even sadder over the weekend. Tharp’s text read simply: “Raymond Beadle died at 4 a.m. Dallas time.”

Beadle, who had been too sick to travel to Michigan in September to accept the most recent honor in a feted career – induction into the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America – died after being unwell for the past few years, including having a heart attack two years ago and another in July. In the end, multiple issues arose, and his body gave out two months short of his 71st birthday.

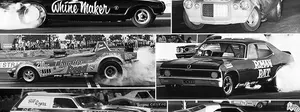

Beadle's success in so many arenas is well-known and well- documented – in drag racing (three Funny Car championships each in NHRA and IHRA, including both in 1981), NASCAR (1989 world champion), and the World of Outlaws, the latter two as an owner – that I don’t really even need to relate it here. I’d steer you instead toward the thoughtful and encyclopedic biography that Todd Veney wrote for us in 2001 as part of our Top 50 Drivers list (Beadle was No. 20). If you want to see all of the Blue Max cars (and a few others) that Beadle drove and a history of what each accomplished, check out the companion column I wrote this week for the National Dragster website, Raymond's Rides, or relive the history of the Blue Max in this column I wrote here two years ago, which includes an interview I did with Beadle and his memories of those early days with Harry Schmidt.

No, Beadle gave so much joy to so many folks – his friends, family, fellow racers, and, of course, the legion of fans who clamored for the Blue Max – that I wanted this column to be about the man and those who knew and loved him. Naturally, I had spent time interviewing Beadle throughout the years, but this list needed to be more personal. Tharp. Don Prudhomme. Kenny Bernstein. Billy Meyer. Dave Settles. Dave Densmore. Steve Earwood. “Waterbed Fred” Miller. Dale Emery.

In just two days, I tracked them all down, and each was eager and honored to speak of his memories of a great racer and generous friend who was a whole lot of fun to be around. They shared some great stories; unfortunately, many of them began with, “You can’t print this, but …” What I can print is presented below, with deep respect and appreciation.

From left, Don Prudhomme, Richard Tharp, and Raymond Beadle in 2011 at Prudhomme's birthday party

|

|

harp and Beadle were inseparable buddies since the 1970s, two larger-than-life Texans who raced and partied together and still enjoyed one another’s company long after the party ended. They lived less than five minutes apart in the Dallas area, talked pretty much every day, ate supper together sometimes five nights a week, and just plain ol' hung out with Beadle’s other close friend, Tommy “Smitty” Smith. For Tharp, losing Beadle was like losing a brother.

That he had to watch his friend’s long and painful descent to his passing has worn heavily on him, as he was there every step of the way, encouraging and consoling – and even chastising -- his pal. When the end neared and Beadle’s body began to shut down, Tharp could barely stand it, and his passing, though seemingly inevitable, hit him like a ton of bricks.

“It’s tough, tougher than I thought it would be,” he admitted, the sadness clear in his voice. “This got my attention harder than anything I’ve ever experienced in my life. I still really can’t believe he’s gone.”

True to his nature, through his last tough months, Beadle put on a brave face for his friends, insisting he would be all right, but when he allowed his daughter, Michelle, to admit him to the hospital last week, Tharp knew the end was near. “It just killed me; he was trying so hard not to have anyone go out of their way or feel sorry for him.”

The long friendship that ended Monday began in the late 1960s, when both were racing in Top Fuel. When Beadle moved to Dallas in the early 1970s to drive for Mike Burkhart, Tharp was already there driving the Blue Max car, whose lineage they would later share when they reunited in the late 1980s and Tharp took over for Beadle in the cockpit in a last hurrah.

As Beadle progressed in the 1970s from Burkhart’s ride to Don Schumacher’s well-funded team, Tharp went through a series of rides, and they faced off occasionally until Tharp went back to Top Fuel with the Carroll Brothers and later Candies & Hughes.

“Even though we were racing in different classes, we went everywhere together,” he said. “We’d fly to the races together and hang out before and after. We had a good time. He was just a good, good guy. I don’t remember anyone being mad at him, and if they were, they didn’t stay mad for more than 10 minutes. You might want to break his neck one minute, but 10 minutes later, you’d want to hug his neck.

“One thing about Raymond: When you were his friend, you were his friend forever, and, believe me, I tested him pretty good. He bailed me out of a lot of trouble over the years. He helped so many people over the years, and you never had to ask him to help you. He’d just show up with whatever you needed to get back on your feet.

“I’ll guarantee you one thing," he added. "When they made Raymond Beadle, they threw the mold away. There’ll never, ever, be another guy like him.”

Old pals reunited: from left, Beadle, Bill Doner, Billy Bones, and Prudhomme, at Prudhomme's party in 2011 (Gary Nastase photo)

|

|

ven though he was the guy who ended Prudhomme’s four-year reign as Funny Car king, “the Snake” always liked Beadle, from the heat of Funny Car battle in the 1970s right until the very end. After a family visit to Louisiana, Prudhomme stopped in Dallas and got together with Tharp to see their old friend the week before he died.

“He couldn’t leave the house, and I think he went back into the hospital that night, but when I left there, I pretty much knew it was going to be the last time I saw him; that hurt a lot,” he said. “We sat and talked for a long time; it was cool to have that time with him.

“Raymond was always a guy that I really, really liked. We used to battle each other on the track, but we used to have fun when we hung out. He was always a pleasure to be around. We used to pal around with a bunch of guys – ‘Waterbed Fred’ and Billy Bones, Bill Doner, Richard Tharp – to hang out in Dallas, go to Campisi’s; we were tight. Outside of ‘Mongoose,’ I don’t know there was anyone inside of racing that I was tighter with than Raymond.”

That Beadle felt the same was obvious when he and Tharp flew to Los Angeles in April 2011 for Prudhomme’s surprise 70th birthday party at the NHRA Museum. It was a long and mutual admiration and friendship.

I asked Prudhomme how he – a notoriously all-business guy when he was racing – was friendly with one of the few guys who could hold his own against the Army cars.

Despite waging war throughout the 1970s, including in the exciting 1975 U.S. Nationals final (above), Prudhomme and Beadle remained great friends. |

|

“I wasn’t friendly with anyone who could beat me; let’s make that perfectly clear,” he said with a laugh, mostly at the memory of himself. “I always wanted to not like him, but I couldn’t help but like him. He’d beat you, and at the other end of the track, he’d almost always sound like he was sorry he beat you. It’s funny to think of it now, but we were all best friends. Hell, I was the best man at ‘Waterbed Fred’s’ wedding. We were a lot tighter than anyone ever knew or could imagine.

“That whole Blue Max thing was pretty impressive, with Raymond and ‘Waterbed’ and Dale Emery and their 10-gallon hats, cowboy boots, and long hair,” he marveled. “And, I’ll tell you, you never had a bad time hanging out with Raymond, before or after the race.

“What I remember about that team was I think Raymond was one of the first guys who only drove. Most of us back then were drivers and tuners, but he actually had a crew chief [first with Schmidt and then Emery]. I was working my ass of on my car, and I’d see him kicking back and relaxing. He took that to the next level that you see today and taught us all something.

“He was always thinking; when he had his NASCAR team, he was the first guy to have a condo – hell, he bought two – [on the first turn] at the Charlotte track, and now they’re worth 10 times what he paid for them. We’d go there and hang out with him, and he’d treat us like gold. He treated everyone that way. Even if he didn’t have the money, he’d buy everyone dinner. He wouldn’t let you buy. I remember the first time I bought him a meal, he was almost insulted.

“We had a lot of good times; Fred Wagenhals [of Action Performance] had a cabin, and we’d all go up there: ‘Waterbed’ and his gal, me and my wife, Lynn, Raymond and [wife] Roz, and Ed Pink and his wife would go to the cabin, and Raymond would be up early every morning cooking for us, bacon and sausage and gravy stacked up -- he could fix a meal. He loved cooking and loved to eat.”

He ended our conversation by saying, “I can’t say enough good things about him,” and apparently he couldn’t. A day after we talked, I got a late-night text from Prudhomme that read, in part, “Just thinking about Raymond … He was probably the coolest guy I ran into in drag racing. Going to miss him.”

Wow. If “the Snake,” the epitome of cool (as even the L.A. Times noted), calls someone else cool, you know he was. Awesome.

(Above) Beadle and Billy Meyer, friends since the early 1970s, shared a laugh during a Legends Q&A at the 2011 national event at Meyer's Texas Motorplex, where Beadle was a regular visitor. (Below) Beadle also took part in that year's Track Walk.

|

|

|

illy Meyer was feeling pretty melancholy when we talked about Beadle’s passing. This was the first year since he opened Texas Motorplex in 1986 that Beadle hadn’t been there, first as a racer and in the 25 or so most recent years as an honored guest in Meyer’s private tower suite. Beadle was too ill to come to the race.

Meyer’s admiration of the legend stems from his earliest days in the sport, in the early 1970s, when Beadle became a mentor to him, not so much with driving tips but how the teenage Funny Car phenom with a sometimes short fuse should handle himself otherwise in the world.

“He was a really good friend,” said Meyer. “He was about 10 years older than me and showed me the ropes about sponsorships and how to handle stuff, when not to blow up at people. I was a ‘damn the torpedoes’ kind of guy back then, and he helped me calm down.”

Meyer, who was still in high school during his first two years in Funny Car, would often ride to the races with Beadle (who then was driving for Burkhart) while both raced on the Coca-Cola Cavalcade of Stars circuit, and Beadle’s wife at the time, Holly, would tutor him in English. “I was not a good student in school,” he admits.

Meyer has fond memories of being with Beadle and Paul Candies, with whom Meyer was especially close and whom we also lost last summer, for huge post-victory dinners that either would stage if their teams won. “We’d go to dinner, and I know they spent more than we won. It was the best food you could get, Bananas Foster and bottles of champagne. Somehow I was in on that clique. It’s amazing the fun we had. Now they’re both gone. It’s a big loss.”

Beadle could also thank Meyer for “Waterbed Fred” Miller, a key member of the Blue Max crew. Miller had worked on Meyer’s car until it had to be parked as part of his land-speed effort in 1975 and joined Beadle’s team during that time.

Meyer also acknowledged Beadle’s business acumen, especially when it came to apparel. Beadle is widely accepted as the guy who moved the needle on fan engagement with wearables. Racers had been printing and selling T-shirts for decades, but Beadle took it to a whole other level. I can’t tell you the number of foxy chicks I saw running around the pits with Blue Max halter tops in the 1970s.

“He really took it to a whole new level, and I think that’s because he was selling the Blue Max brand and not his own name,” agreed Meyer. “The name ‘Raymond Beadle’ on a T-shirt is not going to sell like the Blue Max. He got so successful at it that NHRA had to begin to regulate how those sales went on, which led to MainGate [NHRA’s souvenir vendor, then known as Sport Service] and the racer T-shirt trailers you see today.”

It wasn’t the first time that Beadle got NHRA's attention. Along with Meyer and Candies, the trio, leaders of an owners association, orchestrated the legendary Funny Car boycott of the 1981 Cajun Nationals, demanding higher purses and, secondarily, better safety.

Densmore, who with Earwood was doing NHRA’s PR at time, noted, “The drivers specifically targeted the Cajun Nationals because it wasn’t one of the major [events], and Raymond told us they didn’t want to hurt the NHRA, they just wanted to get someone’s attention. It worked.”

"Waterbed Fred" Miller was a key member of the Blue Max crew from beginning to end. (Below) Miller, right, shared the winner's circle at the 1975 U.S. Nationals with car owner Harry Schmidt, left, and Beadle.

|

|

|

s mentioned earlier, Miller was one of the trio of key Blue Max crewmembers during the championship years, along with Dale Emery and Dee Gantt. He actually preceded the other two, joining forces with Schmidt and Beadle after Meyer parked his team after a late-season match race at Orange County Int’l Raceway. It was a chance encounter with Schmidt at Pink’s Southern California shop just days after becoming unemployed that got him hired to wrench on the Max, which Schmidt and Beadle had recently decided to resurrect.

Miller, not a Texan like the rest of the gang but a native of Mansfield, Ohio, was working in the motorcycle shop owned by Bob Riggle (of Hemi Under Glass fame) in the early 1970s when he met Emery and Gantt, who at the time were working (and, in Emery’s case, driving) for Jeg Coughlin’s Funny Car operation. They offered Miller a chance to crew for them for the weekend, and he never looked back. When Coughlin parked the car after the 1973 season, Miller went to work for Meyer, then a year later as the lone crewmember on the new Blue Max. Beadle, Schmidt, and Miller barnstormed the country, running NHRA, IHRA, and match races until Schmidt burned out.

When Emery and Gantt joined the team a few years later, it was a strong mix of experience. Emery had become famous driving the Pure Hell fuel altered and raced in Funny Car until breaking his arm in a scary crash in Burkhart’s Camaro at the 1977 U.S. Nationals. (It was also Emery who bestowed upon Miller his indelible "Waterbed" nickname, not for any '70s-style debauchery Miller had committed but for his repeated failed attempts to repair a leak in his water mattress; "It started out as a pinhole and by the time I was done 'fixing' it, there a hole big enough to stick my head in," recalls Miller. "Emery would see me and say, 'There goes 'Waterbed Fred' and it just stuck.") Gantt also had a long history in the sport, wrenching for guys like "Wild Willie" Borsch and Fred Goeske, and was on Larry Fullerton’s 1972 NHRA championship-winning Trojan Horse team. It was a powerhouse team, and Beadle treated his people well. Miller also thought there was none better than Beadle as a driver and a boss.

“I don’t ever remember him raising his voice,” he remembered. “Even if someone made a mistake, he’d never be up your ass about it. He always had the same demeanor, whether he was racing at Indy or walking around the shop. He never got rattled in the car, never paced before getting into the car. He had ice water in his veins. He had a good eye for hiring people, and he hired the best guys around to work in our shop, and he treated everyone well.

“Pat Galvin was telling me the other day how he and Donnie Couch were just ‘two grunts’ working on race cars – not even on the Blue Max -- and how Beadle would grab them up to go to dinner or to a Bruce Springsteen concert with everyone else. Everyone went; that was how Beadle was. He didn’t choose who was cool or not; he treated everyone the same. It wasn’t like he ate at the steakhouse and you ate at McDonald’s.”

Miller, Beadle, and "friends." Beadle saw to it that there was always a good time to be had in the Blue Max camp.

|

Miller was there “for every win and every loss” of Beadle’s great Funny Car run with the Max and later took a position in Charlotte with Beadle’s NASCAR team, where he saw firsthand Beadle’s impact on that sport, thanks to his drag racing roots.

“We had been using titanium on the Funny Car for a long time, and when we brought it to NASCAR with titanium driveshafts and spindles, they freaked out,” he remembered with a laugh. “They didn’t have a clue what it was. It was like it was moon metal and scared the crap out of them. We had been coating our pistons and camshafts – anything that moved and had friction -- for years, but we were one of the first guys to do it in NASCAR. I thought they were going to have a cow. And the people that Raymond hired, they all went on to greater careers in NASCAR because of him.”

Beadle seemed to know everyone, especially in the music industry, from Willie Nelson and Bob Seger and the guys in their bands, and he was good friends with E Street Band saxophonist Clarence Clemons and the guys in Springsteen’s band, including “the Boss” himself. When the Springsteen show pulled into Dallas, there was a special Blue Max room backstage, and everyone had all-access passes for the whole Born in the U.S.A. tour.

(Side note: As a huge Springsteen fan, I went to a lot of his concerts during that time and remember seeing Springsteen at the L.A. Coliseum in 1984 return to the stage for encores wearing a Blue Max hat and singing “Stand On It,” a racing-themed tune. I may have been the only person in the place who was wowed by that, but I remember it as if it were yesterday.)

Miller, who went on to work with Action Performance in the collectibles world, stayed in touch with his longtime boss and friend. “We still talked a lot on the phone, and I would see him at various functions. When I’d come to Dallas, I’d stay with him. I'll miss that."

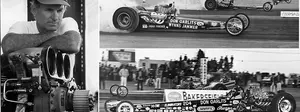

(Above) Beadle, left, and Dale Emery won four Funny Car championships together from 1979-81, including both NHRA and IHRA crowns in 1981. (Below) Before they joined forces in late 1977, they raced against one another, including earlier that year, with Emery driving for Mike Burkhart, for whom Beadle had driven earlier in his career. (Steve Reyes photo)

|

|

The recent Blue Max reunion: front row, Beadle and Richard Tharp; back row, from left, Dale Emery, former Blue Max driver Ronny Young; Fred Miller; crewman Scott Nelson, and Tommy "Smitty" Smith.

|

|

hile Beadle was the marketing and driving force behind the Blue Max, crew chief Emery was certainly his mechanical enabler. Emery, an Oklahoma native afforded full-on Texan status by his affiliation with the Blue Max and his current residence in Denton, Texas, went to work for Beadle in late 1977, after breaking his arm in an accident at the U.S. Nationals. After a problem-plagued 1978 – highlighted only by a win at the season-ending World Finals – they won the NHRA championship in 1979, 1980, and 1981 and joined the last one with a simultaneous IHRA championship. (Beadle won his two previous IHRA championships before Emery joined the team.)

The duo first met at Chaparral Trailers, where Emery worked while not racing; Beadle stopped by looking for a trailer for the new Blue Max effort. After his crash in Indy, the plaster was barely dry on Emery’s cast before Beadle offered him a job. Emery hadn’t intended to retire from driving but was intrigued by Beadle’s offer to tune the Blue Max. The fact that he already knew Gantt and Miller certainly didn’t hurt. Beadle headed off to England for a series of match races, and both guys mulled it over for two weeks before Emery accepted.

“I told Raymond I’d never tuned for anything I didn’t drive but that I would try it; it seemed to work out OK,” he said. “We did pretty good.

“He always treated us right; if we needed something, he’d help us out. He really gave me an open hand of what I could do with the car, and I liked experimenting, which is why I came up with the dual-mag deal and some other things. I was always trying to make it run better.”

When it came to rating his driver, Emery didn’t hesitate. “He was a money driver; he never got rattled,” said Emery, with the admiration clear in his voice. “If we made it to a final, we knew we never had to worry about him being late.”

Emery stayed with the Blue Max to the bitter end in 1990, when the car was essentially underfunded and not equipped with the best parts. It was at least in part Emery’s urging that got Beadle to finally sell the team.

“He was pouring all of his money into the NASCAR team because that was his deal at the time,” he remembered. “I talked to him and told him we couldn’t keep on doing what we were doing. We didn’t really even have parts good enough to run match races. I told him he needed to sell the deal while it still had a good name, and he did.

“We all got together –- Beadle, me, Fred, and a few other guys -– for a Blue Max reunion a couple of weeks ago in Dallas,” he said. “It wasn’t a great big deal, but it was great to get everyone together one last time. I still talked to him every week. I would just check up on him and see how he was doing. We’ve always been good friends; we raced together and had a lot of fun. I really liked the guy.”

Kenny Bernstein, left, and Beadle watched the "Texas Chainsaw Massacre" unfold.

|

|

|

hen most drag racing fans think of a tie between Beadle and Bernstein, they inevitably think about the 1981 Winternationals and the “Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” in which Bernstein offered up one of his spare bodies to Beadle, who had blown the roof off of his car in winning his semifinal race. The roof from Bernstein’s Budweiser King Arrow was cut off and crafted to Beadle’s Plymouth Horizon in time to make the final (which Beadle lost).

But the two go way, way back further than that: They were junior-high and high-school classmates in Lubbock, Texas, in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Although they knew each other, they didn’t hang out, and it wasn’t until Bernstein returned to Lubbock after attending college in Dallas that he realized that Beadle was interested in racing.

Bernstein drove Top Fuel for Vance Hunt, the Anderson brothers, and Prentiss Cunningham early in his career, and Beadle also later drove for Cunningham before both transitioned to Funny Car in the early 1970s.

“I spent a lot of time with Raymond after that, at a place we called Gasoline Alley in Dallas, where we’d all hang out or had shops. I was with the Engine Masters [Ray Alley], and he was driving for Burkhart. We raced against each other a lot in the 1970s and ‘80s when we were in our heydays of racing.”

Bernstein, long acknowledged as drag racing’s master marketer, thought highly of Beadle, who, unknown to many, had taken marketing classes himself.

“He was a great promoter; he was always hustling and putting things together and trying to take it to the next level,” said Bernstein. “He was a real go-getter, in everything from sponsorships to merchandising.”

Despite their tough battles for Funny Car supremacy in those days, the two former school chums remained friendly. “We stayed pretty close throughout the time until he got out of racing, then we kind of lost touch as we both did our own things, but the times we had together were very special and memorable,” said Bernstein.

(Above) Dave Settles drove the short-lived Blue Max Top Fueler for Beadle and two partners in 1979. (Below) Settles, left, and Blue Max crew chief Dale Emery

|

|

|

ave Settles was another fellow Texan with a long relationship with Beadle. Settles saw Beadle socially throughout the later years, always in Meyer’s suite at the Dallas event and regularly at the yearly winter get-together of former Texas racers in Denton. The former driver and crew chief, who remains active in the sport building fuel pumps, met Beadle in the early 1970s while driving for the Carroll Brothers team. Although Beadle also raced Top Fuel at that time, he soon went to Funny Car and Settles stayed in Top Fuel, and they never did race one another, though they did race together.

In 1979, Settles was the driver of the short-lived Blue Max Top Fueler, which was owned by Beadle and financed by well-heeled Dallas-area developers Foster Yancey and Brad Camp, who also were minority owners of the Dallas Cowboys and handpicked Settles as the driver and crew chief. The car debuted midseason and ran only eight races – winning the IHRA Springnationals and scoring a runner-up at the NHRA Summernationals – before being parked.

I asked Settles why Beadle, who was en route to winning his Funny Car championship, would also put his foot into the Top Fuel waters.

“Raymond was big on getting exposure for his sponsors and his team, so it made sense for him, I guess,” said Settles. “He thought he could never get enough exposure, and when it came to that, he was always on his game. Me, I just wanted to hit the pedal.

“The car’s first race was the big IHRA Springnationals event in Bristol; I’ll never forget it,” he recalled wistfully. “I pulled up there for my first run Friday, and people started cheering and going on and on. I couldn’t figure out what they were cheering about – it’s just a couple of Top Fuel dragsters. It didn’t dawn on me until later that it was because of the Blue Max name.

“I think Foster and Brad realized the value, too. The Blue Max was the ‘in’ deal in Dallas; everyone knew about it – no matter what sport you were in -- and everyone knew Raymond. Being around Raymond was a fun place to be; there weren’t too many dull moments.”

|

|

s mentioned earlier, Earwood was running NHRA’s Publicity Department with Densmore in Beadle’s heyday, and as a fellow lover of good times, they enjoyed one another’s company.

"He believed in taking care of his sponsors and press and publicity before a lot of the rest of them did,” he recalled. “He was great to me and Densy.

“He really changed our industry, no doubt. He was a great businessman racer – in a different mode than a Rick Hendrick or a Roger Penske -- but also just had a lot of common sense. He was first-class all the way. When he started racing NASCAR, back in those days, if the guys had a wreck, they’d just beat the fender out for the next race, but ol’ Beadle wanted his cars perfect every time.

“Raymond got along with everyone --Bernstein, Meyer, ‘Snake’; sometimes you couldn’t even put those guys in the same room at one time, but Raymond got along with all of them. He got along with everyone. And generous? When he’d take people to dinner after a race, it would be 40 or 50 people. He’d just call the hotel and rent out the restaurant. We had a lot of fun back then. He was a helluva personality; we’ll never see another one like him. He was really something. He lived a very full life and did it right.”

|

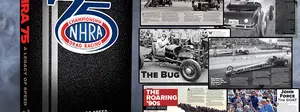

eadle was a superstar of the 1970s and 1980s, so it was only fitting that we’d hear from today’s Funny Car star, John Force, who inducted Beadle into the International Drag Racing Hall of Fame, as you can see in the clip at right (thanks to reader Dave Wesolowski for the link!).

Wrote Force, "In my long career, there have been five people that I have looked up to: ‘Big Daddy’ [Don Garlits], Shirley [Muldowney], [Don] Prudhomme, [Tom] McEwen, and Raymond Beadle. I have taken his passing very hard, and it hurts me personally. I saw what kind of team owner and driver he was as well as what kind of creative promoter and teammate. He had the most loyal team with guys like Fred Miller, Dale Emery, and Dee Gantt. They were together through good times and bad. Our legends are getting older, and we have to appreciate them every day.

"I saw Beadle roll the Blue Max over in a terrifying crash. He has ice water in his veins because he just got out and put his hands over his head in triumph. I have never heard the roar of the crowd like that.

"Raymond surrounded himself with the best people, and they fought together every day. That is how I have run John Force Racing every day. Loyalty is the key, and so are principles. Raymond taught me that, and that is why I will miss him so much. In my early days, he helped me so much, and I thanked him every chance I got. He was a legend and one of the best who will be missed every single day."

|

|

will close with this great essay written by Densmore, who, like Tharp, felt the loss of Beadle on a very deep level. He sent it to me the day that Beadle died, and I want to share it here.

I know they say life goes on, but for me, at least, it will go on with far less enthusiasm, less fun, less intrigue and less real joy in the absence of Raymond Beadle, the face of Blue Max Racing Inc. who on Monday lost his battle with heart disease and a variety of other physical demons in the ICU ward at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

The irony is that it is the same ICU ward in which I spent so much time with John Force after his 2007 crash at the Texas Motorplex. Force finally walked out of the hospital. After suffering an apparent stroke, Raymond did not.

I’ve had to deal with the passing of so many of my heroes the past few years – Wally Parks, “Diamond Jim” Annin, my dad, Dr. Al Densmore, Dale Ham, Eric Medlen, Lee Shepherd, Paul Candies. All of them enriched my life and, through their very presence, made even my worst days somehow palatable.

But this death has been particularly difficult for me to accept. I don’t know why, but I do know that I have a hole in my heart as big as Texas. We were friends for almost 40 years, linked by our West Texas roots, our love for drag racing and our mutual disdain for the status quo. “That’s the way we’ve always done it” was a mutually irritating phrase.

Of course, that outlaw attitude is what made Raymond larger than life. He was Force’s idol long before the 16-time champ won his first race. In fact, Force still likes to tell how Raymond provided his team’s first uniforms. They were only Blue Max T-shirts, but when Raymond gave them to Force at Spokane one year, they became the first matched outfits in Brute Force history.

At a time when 90 percent of the sponsorship in drag racing was automotive, Beadle went after the mainstream market and landed deals with English Leather and Old Milwaukee beer. The English Leather era is itself worthy of a tell-all book, but he also had deals with NAPA and Valvoline and, at the end, Kodiak tobacco.

Raymond approached the sponsorship equation not with hat in hand, as was typical of the era, but from a position of strength. He put together deals with Ford and later with Pontiac, although I’m not sure GM ever got back all its cars. Having studied marketing in college, he applied those lessons to the sport. The result was the creation of what today is a massive collectibles market.

He sold so many T-shirts and hats and hat pins and halter tops, especially those that came with the “custom fit option,” that it compelled the NHRA to rewrite the rules governing sales. In essence, he made it possible for MainGate to enjoy the success it does today because NHRA determined that if they were providing the arena for such entrepreneurship, they should get some of the profits.

He was, in my estimation, the perfect driver because, like Lee Shepherd, he was totally unflappable.

Dennis Rothacker

|

When his first wife, Holly, grew temporarily hysterical after his 1982 crash at the Gatornationals in Gainesville, an unruffled Raymond told her that if she was going to react like that, he wasn’t going to let her come back because it was very distracting.

That crash also demonstrated his flair for the dramatic. After barrel rolling the Blue Max and with the crowd holding its collective breath, he climbed out through the escape hatch, hands over his head in mock triumph.

Although he won just 13 times, he won three successive NHRA Funny Car championships (1979, 1980, 1981), the first ending Don “the Snake” Prudhomme’s four-year reign in the U.S. Army car.

His calm demeanor was aptly demonstrated in 1975, the year he convinced Harry Schmidt to partner with him in the resurrection of the Blue Max. That first year, he was in the final round of the biggest event in the sport, the U.S. Nationals, and he was racing one of the biggest names on the planet, “the Snake.”

After the burnout, the car sprung a small oil leak. Fellow Texan Richard Tharp, who was at the starting line as a spectator, raced back to the crew cab for a wrench, but before he could return, "Waterbed Fred" reached in and hand-tightened a loose fitting. Raymond then calmly pulled to the starting line and, ignoring all the drama, won the race.

How big was Raymond Beadle? Well, when Bill Center, the erstwhile motorsports writer for the San Diego paper got a new dog in the ‘80s, he named him “Raymond Beagle.”

Having conquered drag racing, Raymond moved on to NASCAR, where he won races with Tim Richmond and a championship with Rusty Wallace. He also went racing with the World of Outlaws, where he almost won a title with Sammy Swindell.

Those were unbelievable times. It was, as I am fond of telling each new audience, a time when sex was safe and drugs were legal. That’s only a marginal exaggeration. We flew to NASCAR races, flew to sprint-car races. It was the best of times, and Raymond always went first class, with or without the wherewithal to do so.

|

There was a time when money was really tight, and every day included phone calls from irate creditors. Raymond knew every dodge in the business, any scam that might win him a little more time to “put something together.”

“Forgetting” to sign the checks, envelopes without postage, items sent to erroneous addresses, but my favorite was one day when he signed a batch of checks and gave them to the office staff. The girls dutifully put them in the proper envelopes for postal pickup.

Unbeknownst to them, Raymond had snuck back into the office and liberated the envelopes so, when the calls began anew, the staff was none the wiser, informing callers with proper indignation that “I know we sent them out because I put them in the envelopes and in the box myself.”

Raymond always was making deals, and irate creditors were part of doing business. He used to tell everyone in the office not to get so mad. “It’s nothing personal. They only want their money.”

It was amazing to me that he could leave even some of his closest friends hung out on this deal or that deal and, still, when it came to crisis time, they’d be there for him. It was that way up until Monday.

He moved comfortably in any circle. He was pals with princes and paupers. Those in his circle regularly were treated to Willie Nelson and Bruce Springsteen concerts, and the late Clarence Clemons and other band members were regulars at the races – and at the victory parties that often followed.

Raymond got Willie to perform at SEMA, a function at which he and Holly got involved in a marital spat that resulted in her storming out and flying back to Texas. When Raymond returned, she asked him about her mink. She’d left it on the back of the chair. Raymond left it there, too.

Part of Raymond’s ultimate undoing was the fact that he developed a love for cooking. Actually, he developed a love for eating what he cooked, and, as a result, let’s just say that he was a little above his fighting weight at the end, which recalls one final story.

Former National DRAGSTER staffer John Jodauga is an accomplished artist who Raymond commissioned to do a caricature for a press kit cover in the ‘80s. It was typically well done, but J.J., the consummate professional, sent it to Raymond for final approval and asked if there was anything else he could do.

Raymond asked him to take about 10 pounds out of his cheeks. And he meant it, too. Rest in peace, R.B.

Amen. He'll be missed, but the legend of the Blue Max will fly on forever.

I invite fans and friends of Beadle to share their thoughts and memories of the man for a future column; send them to me at pburgess@nhra.com.