A challenging 'Challenge of the Sexes'

|

On Sunday, Alexis DeJoria came within just one round of becoming the third female to win an NHRA national event Funny Car crown before she smoked the tires in the final round against Ron Capps, yet it hardly made headlines. The fact that DeJoria is embroiled in an interesting battle for the Automobile Club of Southern California Road to the Future Award honors with (among others) fellow first-year female flopper foe Courtney Force seemed to be of more interest to the racing community than the fact that yet another female racer was challenging for victory in this once male-dominated sport.

Although just 11 women — Shirley Muldowney, Lucille Lee, Lori Johns, Shelly Anderson-Payne, Angelle Sampey, Cristen Powell, Karen Stoffer, Melanie Troxel, Peggy Llewellyn, Ashley Force Hood, and Hillary Will — have won in a Pro category at an NHRA national event (out of about 50 who have competed), the NHRA Sportsman ranks are filled with scores of female national event winners, including this past weekend in Super Gas, where Emily Lewis took home the Wally. Girls racing, and beating, the boys hardly qualifies as a headline anymore. But, of course, it wasn’t always that way in drag racing. It took years before NHRA licensed a female driver to drive a supercharged race car (Barbara Hamilton, 1964), and it wasn’t until 1977 that NHRA crowned its first female champion in Muldowney.

(By the way, a happy birthday today to Shirley!)

In the 1970s, the feminist movement (known then more colloquially as Women’s Lib) was in full bloom and pop culture was enamored of the novel idea of women competing against men, as evidenced by the sky-high ratings for the September 1973 tennis match between Billy Jean King and Bobby Riggs, a contest hyped as “The Battle of The Sexes.” CBS television execs certainly took notice and created a Challenge of the Sexes TV show, which on three occasions in 1976 to 1978 featured NHRA Drag Racing and all three, of course, featured our own female phenom, Ms. Muldowney.

Shirley Muldowney took part in three CBS Challenge of the Sexes TV shows from 1976 to 1978, during some of the most memorable years of her career.

|

In late 1976, Muldowney and crew chief Connie Kalitta took on Funny Car hero Don Prudhomme, whose Army Monza got a two-tenths handicap start and won two of the three rounds at Orange County Int'l Raceway.

|

|

|

Drag racing was clearly a good choice for the show as motorsports is one of the few sporting endeavors in which men and women not only compete head to head but do so with no handicaps. Unfortunately, none of the three competitions provided a fair and accurate depiction of this rivalry, and the results — Muldowney lost all three — certainly were not indicative of her potential. And, truth be told, pretty much anytime that she raced a guy — from her earliest gas dragster days through the 1975 Indy final with Don Garlits and probably her whole racing career — the announcers had no qualms about making it a “battle of the sexes.” Until she cemented her reputation as a multitime world champ, she was always on trial.

The first of three — all of which were staged at Southern California’s Orange County Int’l Raceway — was definitely the weirdest. Held just before the 1976 World Finals, which both drivers won, it pitted Muldowney’s dragster against Don Prudhomme’s all-conquering Army Monza. Muldowney was just a few months removed from her historic victory at the NHRA Springnationals in Columbus. Prudhomme, of course, was at the tail end of the most remarkable season in Funny Car history, having already won six of the seven events that year (missing only in Indy) in a car that was nearly unbeatable not only for its performance but its consistency.

Prudhomme’s car was given a two-tenths handicap start — the respective national records were further apart, at 5.63 and 5.97 — and each ran once in each lane, with lane choice for the third heat decided by a coin flip.

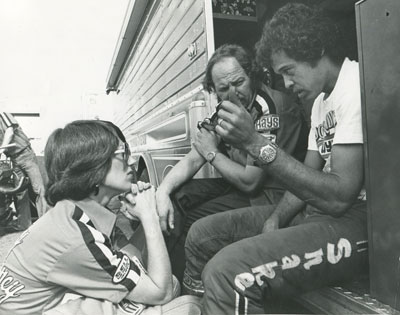

Prudhomme won the first round on a holeshot, 6.31 to 6.16 (the ND report surmised that the odd offset had upset Muldowney’s concentration). Between rounds, the duo were interviewed by hall of fame sportscaster Vin Scully, who brought a touch of class to the affair as the lead commentator, along with Phyllis George.

The second round was over quickly as “the Snake’s” Monza lit the tires at the green. Prudhomme pedaled it once, lit ‘em up again, and shut off to watch Muldowney blister the OCIR timers to a 6.03 at 240 mph.

The deciding round was run just before dark, and the cooling (and presumably unprepped) track vexed them both. Prudhomme got off to a decent pass of 6.36 at 233.76 while Muldowney blazed the tires, expertly pedaled, but came in second with a 6.29, again at 240 mph.

Neither driver could have been pleased with their performance, but the prime-time TV publicity windfall for both was no doubt a big one for drivers largely accustomed to working outside the television spotlight. As Nevin R. Johnson once famously said, “This is the kind of spontaneous publicity that makes people!”

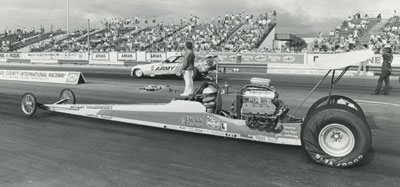

In late 1977, Muldowney squared off with Garlits in another two of three at OCIR. They were interviewed by hall of fame announcer Vin Scully but had only one race because breakage claimed Muldowney's car.

|

|

Muldowney's team thrashed in the pits to repair a broken rear end but missed the second-round call, forfeiting the challenge to Garlits.

|

A year later, Muldowney was back for the TV lights at OCIR, with Garlits as her opponent. A lot had happened to Muldowney in the year since, and she had already claimed her first world championship by the time the cameras rolled at OCIR Nov. 18 after the conclusion of the season.

The Muldowney-Garlits rivalry — never a quiet one — had accelerated commensurate with her on-track success and publicity. She put together a tidy three-race winning streak, Columbus again, Englishtown, and Montreal, and was featured in Sports Illustrated and People magazines. Garlits was quoted as saying in one of the many newspaper articles proclaiming her success ”How can those guys let ‘that girl’ beat them like that?”

Garlits hadn’t been able to do it himself, at least not on the national event stage. He went to only two finals that year — runner-up at the season-opening Winternationals and a win at his hometown Gatornationals — and finished a distant ninth in the points but had a lot more success against her on the match race trail, where it was always a heated “battle of sexes” between the two. Prior to the OCIR match, Garlits had beaten her two straight at Fremont Raceway (5.93 to 6.10 and 5.89 to 5.95) and at Irwindale Raceway’s Last Drag Race (6.01 to 6.03 and 6.02 to 6.14).

Unlike the Prudhomme showdown, this one was heads-up. Garlits won the coin toss and first-round lane choice and chose the spectator lane. Muldowney was out first on him — as she almost always was — but ran into tire shake that broke the rear end. Garlits won with a non-representative 6.47 at 220 mph.

The rules of the contest called for just one hour between rounds, but Muldowney’s crew was unable to make the repairs in time, and Garlits was declared the winner. Scintillating drama it wasn’t, but again, the public got to see the face of the feud up close and personal when the show aired the following February.

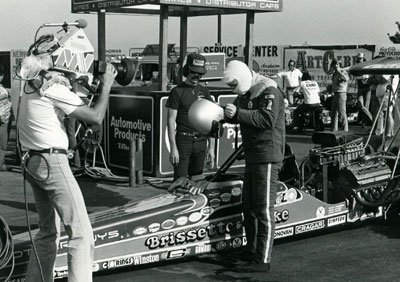

In November 1978, Muldowney was back to challenge newly crowned Top Fuel champ Kelly Brown, right. Breakage again played a role in deciding the outcome. |

|

Muldowney was game again the following year to take on the man who had claimed her crown, 1978 Top Fuel champ Kelly Brown in the Brissette & Drake Other Guys entry. The two champs squared off Nov. 3 at OCIR, just after the World Finals, and, again, the outcome was more befitting the Twilight Zone than the Challenge of the Sexes.

After the traditional pre-race interviews with Scully and new co-host Cathy Lee Crosby, both drivers burned out but a brake line on Brown’s dragster snapped on the burnout, and he was unable to back up to the starting line. A half-hour later, they were back on the line, where Brown raced to a 6.05 to 6.35 win, with the salt in Muldowney’s wound being a rod out the side of her engine block.

After a prolonged track cleanup, round two went to Muldowney with a piston-eating 6.23 to Brown’s 6.45, but this time, it was Brown’s turn to suffer more breakage; he broke the rear end at the 1,000-foot mark.

By that time, the day had grown short and, invoking the power of TV, the producers announced that to beat the fading light, the final and deciding frame would be held just 30 minutes after the second round. Brown’s team was unable to make the quick turnaround, but rather than give Muldowney the win as Garlits had been awarded against her the previous year, the producers made Muldowney race for it. Apparently good TV was more important than fair competition.

In order to “win” the third round, they decided that she’d have to beat Brown’s best e.t. — his first-round 6.05 — and although she came close with a parts-pitching 6.07, the overall win went to Brown, who questioned out loud, "How can anybody be declared the winner in something like this?"

Other than the PR windfall, it’s probably just as well that the challenges ended there and allowed the racers of both sexes to go on challenging one another as racers instead of opposite sides of the gender tree.