The rise and fall of Orange County Int'l Raceway

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Orange County Int'l Raceway has been gone 25 years, eight years longer than it was in business from 1967 through 1983, but it's still fondly remembered by those who worked, raced, and played there.

When it was built, it billed it as "the Super Track," and when it opened its doors to the public Aug. 5, 1967, it was crystal clear that it was not simply marketing hype. Much as today's racers and fans are wowed by the opulence of Bruton Smith's new zMax Dragway, such was the case 41 years earlier when OCIR was born. It was that good and that far ahead of its time.

The seed is planted

OCIR actually grew out of a partnership brokered by longtime NHRA Vice President Bernie Partridge, uniting the efforts of two dynamic duos: Larry Vaughn and Bill White, who had grown up on the 80,000-acre Irvine Ranch and knew that the vast area would be a great open spot for a new facility, and Mike Jones, a former designer and draftsman (but then employed as a racing engine designer) and a former competitor in drag racing, dry lakes, and road racing, and his financial backer, newspaper publisher and auto dealer Mike McKenna.

Jones actually had initially been trying to put together a drag racing program for

The Irvine Co., meanwhile, held the lease on the land and had long-term plans to build housing and entertainment for

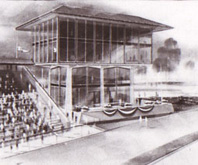

White (who was to be the track's president), Vaughn (secretary/treasurer), and Jones (vice president and general manager), however, promised to build a facility not just with a quarter-mile track and pits but one of unprecedented style and grace, complete with all the creature comforts a fan could expect, surrounded by lush landscaping and a striking architectural design.

They enticed five Orange County residents -- Carroll Cone, owner of Cone Chevrolet; investment banker David Brant; Raymond Martin, owner of amusement facilities at O'Neill Park and Irvine Park and a former midget auto racing track owner in Orange County; and Irvine Co. stockholders Mrs. Myford Irvine and Mrs. David Brant – as investors to supply the capital for a project that initially was budgeted at $80,000 and resubmitted the plan to the board of directors.

The Irvine Co. granted them a 55-year lease to build the track in east Irvine, in the middle of a giant Y formed where the great

Designing the future

Jones did the actual design work and plot plan of the facility, mixing his ideas with guidance from NHRA officials and the best ideas from other tracks around the country. In what amounted to an OCIR mission statement, Jones wrote in the opening-season program, "If there were one basic premise on which Orange County International Raceway was founded, it is that, if the sport of auto racing is to enjoy continued growth and success, facilities must be provided that are commensurate with the professional status of the men and cars competing there. We set out to create an atmosphere, an atmosphere of professionalism, of excitement, yet one of comfort."

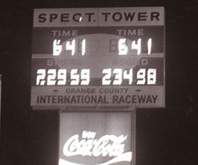

Permanent restrooms and concession stands, now all but taken for granted; underground utilities; a restaurant; a speed shop; a children's playground; a distinctive 40-foot high, three-story tower that housed the administration offices, timing and announcing deck, and a top-floor suite; and a starting-line-based scoreboard were but a few of the features that made "the County" a major step up from previous facilities.

Jones was especially dedicated to creating a safe facility. The track was 75 feet wide and, at 4,200 feet, plenty long. A 300-foot sand trap capped by water-filled plastic barriers was beyond that. He hired Marines from the adjacent airbase at

Jones and his team spent months analyzing patterns of other facilities and running mock races on various track layouts to determine the most functional configuration. Indeed, at one time, the design of the track was configured to run in the opposite direction.

"Spectator comfort has been the most often overlooked aspect of auto racing facilities," Jones wrote in his manifesto. "The

The Orange County Planning Commission granted its approval Nov. 9, 1966, and a joint press conference with NHRA and the Irvine Co. was held the following day at the

Opening day

|

|

Opening day was less than a month later, Aug. 5, 1967, and future National DRAGSTER Editor Bill Holland, who at the time fielded a Top Fueler with John Guedel, remembers it well.

"As one of many local Top Fuel racers in SoCal, we had heard about the plans for OCIR and were anxiously awaiting to see if they were 'for real,' " he recalled. "When we arrived at the grand opening, we were duly impressed by the facility and its management. The rumor was that they'd taken some cues from that noted

No less a hero than Tom "the Mongoose" McEwen was at the wheel of the Guedel & Holland/National Automotive Specialties dragster for the opener. He set low e.t at 7.02 and reached the final but red-lighted to Bobby Tapia in Larry Stellings' entry. (Guedel set the track speed record at 223.88 mph at the Division 7 points meet held later that year.)

Getting going

|

|

|

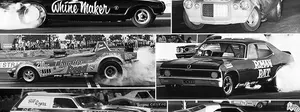

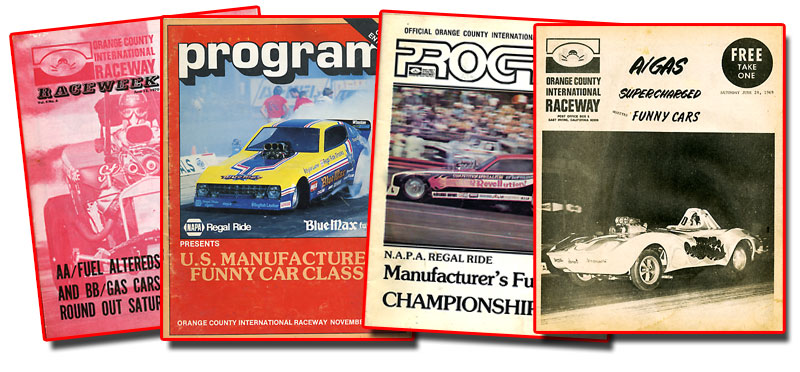

Competition in the early years was stiff from fabled Lions Dragstrip, which was just less than a half hour up the 405 Freeway in Wilmington and Irwindale, just about the same distance to the northwest, but Jones worked hard to develop a Funny Car-heavy formula that worked, and when Lions closed at the end of the 1972 season, business at the gate definitely improved, but the track still struggled. It was Jones who developed the idea to bring together all of the nation's touring Funny Cars for the first Manufacturers Meet and dreamed up the idea of Funny Cars lining the track prior to eliminations, seeing it as a great photo op to help sell the sport and the events.

Early on, Jones understood the challenges of selling drag racing to a public whose images of the sport were not in tune with its growing professionalism, and he saw the media as the key to unlocking that door. He built a then state-of-art air-conditioned pressroom complete with "duplicating machines," telephones, telex equipment, and a snack bar.

"Sports editors, although they are not familiar with drag racing, do know about competition. They know what is and what isn't. They cannot be sold circus acts or 'booked in' races to the extent of having them regarded as major events," he told Drag News in 1969. "We are going to have to pay quite a bit of attention to the public. I think that beyond this it is just a matter of hard work on the part of strip operators. Those racers who become prominent in the sport, to present a good appearance, to be well-spoken when they are around these people, and, most of all, to be honest with them. They aren't familiar with the sport. They are very hesitant to cover it. They would rather not cover it at all, as to make a mistake in coverage. If they are led astray unintentionally or intentionally by racers or strip management, they can set drag racing promotion back a long ways."

|

|

|

Growing pains

Little did Jones know that there would be other, harder hurdles to clear. In the first two and a half years of operation, property taxes climbed by 400 percent, insurance premiums by 15 percent in 1968 and 21 percent in 1969, and even trash-collection fees doubled in the same period. Racers also sought higher purses to offset their rising costs. The worst was still to come.

Although the track opened under NHRA sanction, following Jones' July 1973 departure, the track signed a five-year pact with AHRA. AHRA President Jim Tice brought in Lions and Santa Ana mainstay C.J. "Pappy" Hart as general manager for what amounted to a very short stay that was highlighted by OCIR's first national event and clashes between Hart and Tice's team that led to Hart's resignation. Tice walked away during the 1974 season – new track manager Blaine Laux remained – and millionaire businessman, Pro Stock driver, and Funny Car owner Larry Huff took over June 1, 1974, yet kept the track under AHRA sanction.

Huff, who also had assumed ownership of the Tice-owned Fremont Raceway, lasted even less time than Tice, dropping first

Motocross and speedway tracks and a defensive-driving school had been built, and plans were drawn up to use some of the excess racetrack land for commercial use to increase revenue in the face of rising property taxes and other costs, but the Irvine Co. balked at this idea. The long-term lease that could have kept the track open through 2022 eventually returned to the Irvine Co., which was eager to use the now-expensive land for its intended commercial and residential purposes. Vaughn, the last remaining holdout of the original four founders, however, struck a five-year deal to continue leasing the land.

The famed West Coast duo of Bill Doner and Steve Evans brought their International Raceway Parks savvy to the game, and with Doner's never-shy way of promoting events and Evans' steady hand on the tiller and a return to the NHRA fold, things began to look good at "the County" for a short while, but before long, things got out of hand. Drunkenness and rowdy fans – in the most notorious incident, a 24-year-old man died after being hit in the head with a beer bottle -- were no doubt spurred on by events such as rock concerts staged in tandem with the races and events such as the annual Fox Hunt, which allowed women in bathing-suit attire free entry. As Evans growled on the radio, "Foxes, bring your bikinis!"

Longtme OCIR starter Larry Sutton remembered, "The Doner and Evans regime always had a spectacle, and there were always way too many people and not enough security. There was one race that I ran, and I saw legs all the way down the racetrack with people sitting on the guardrail."

A return to glory

|

|

|

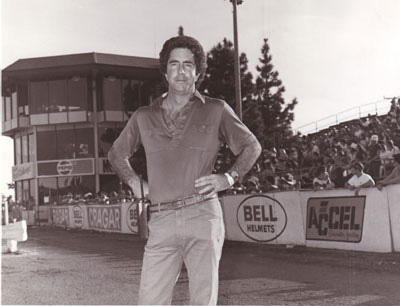

By 1980, Doner, who was in a constant battle with city and county officials about a number of items, had had enough and was eager to get out of the business and retire to Mexico to go sport fishing. Again, NHRA's Partridge helped keep the California dream alive, enticing former Funny Car racer Charlie Allen, whose All-American Boy floppers had prowled the OCIR quarter-mile in days gone by – he was part of the opening-day program -- to take over the struggling ship. Allen had been trying to build a track in

Recalled Allen, "I knew Bill and had raced for him over the years, and we were able to strike a deal to buy all of his assets and the rights to the property. Although I was a pretty good businessman, there definitely were things I didn't know about running a racetrack and mistakes I made, but I wanted to return the track to more of a family atmosphere. We spent $300,000 to $400,000 on a quasifacelift and applied what I thought was good business policy to it, and off we went."

The next three seasons were some of "the County's" best. Families and fans returned in droves, and Allen, general manager Lynn Rose, and veteran track manager Kenny Green annually staged eight to 10 major events a year, including the Manufacturers Meet, 64 Funny Cars, and Summer Showdown, but Allen knew that he'had inherited a lame duck, set to be roasted at the end of the 1982 season.

A last-second reprieve, then goodbye

"I knew the track only had a little over two years left on its lease, so in early 1982, I started trying to negotiate with the Irvine Co. for extra time," Allen told me last week. "I found out that the company president responded to any letter ever written to him, so I got all of the TV and radio stations and the Orange County Register to do stories about how terrible it would be if the track went away and that the fans and racers should all write letters to the company. At one point, he was getting 300 to 500 letters a day. I went from not being able to talk to him to having him call me for a meeting, and one of the first things he said was, 'Can you stop this thing?' and I did and made them the good guys for letting us stay another year."

OCIR announcer Mike McClelland remembered, "As 1982 ended, the specter of OCIR closing was always on everybody’s mind. You had one group that figured 'They’ll never close it' and another group that just kind of laughed at that thought. Early in 1983, construction was started on the first road other than Moulton Parkway (Irvine Center Drive) across the strawberry fields that lay across I-5 from the track. The Alton Parkway bridge over I-5 started rising up from the fields. That’s when I knew it was over. They weren’t building roads across the area without any plans to build on it."

|

|

|

|

That final year, as documented here Monday, was a rousing success that included the popular back-to-back staging of two 64 Funny Cars races, which Allen, showing a bit of Doner-like savvy, played to the hilt, making it seem as if it were a spur-of-the-moment decision to "do it all over again next weekend." In fact, he had already bought the airtime and made the radio commercials.

"We even shut the gates early," he recalled. "We probably would have put a few hundred cars in, but we wanted to be able to say we couldn’t get everyone in and turned away people so we were going to do it again. Doner loved it when I told him that."

Even as the clock was ticking in those final years, Allen considered rebuilding the track elsewhere close.

"We looked for property, but most of it was so hilly that I would have had to spend 4 or 5 million dollars in grading alone, and I didn’t have enough experience to realize that ultimately it might pay for itself," he said. "They finally started developing their industrial park, which had been in the works even prior to me buying the track. They were even putting in huge water lines in the parking lot those last few years, and we had to barricade those areas off during events. My agreement was that I wouldn’t do anything to slow down their development of the property."

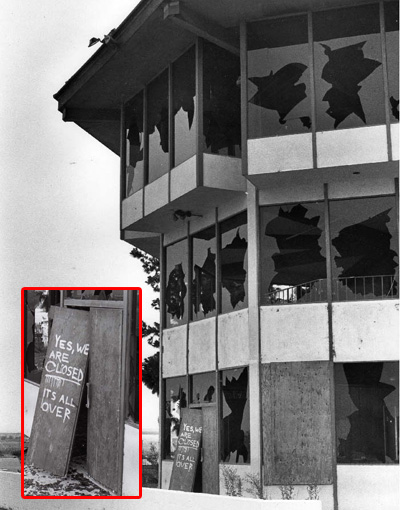

In return for his cooperation, the Irvine Co. allowed Allen, who had begun construction on Firebird Int'l Raceway outside of Phoenix in 1983, to take with him anything he could salvage from the track, and Allen briefly even considered moving the trademark tower to Phoenix. "I got bids on moving the tower, but it was way ridiculous," he said, "but it would have been cool from a nostalgic point of view.

"I think I was very lucky to have the success we had there in the track's final couple of years," he said. "That success made me realize that I wanted to keep doing this, which is why I built Firebird Int'l Raceway." In a weird coincidence, the size of

Kenny Bernstein, who won the Last Drag Race and whose shop was nearby, mourned the loss of OCIR for a number of reasons.

"With it being so close to our shop, we did a lot of testing there," he recalled. "It was such a nice facility and convenient for us. OCIR had such a history of great Funny Car races there, and it was one of the great places to race and, really, the last one standing. Seeing them all go reminds me of the pro football program here. They all left town, and they're still gone. But, to this day, every single time I drive by the

The iconic tower stood for more than a year as work went on around it before it, too, finally was felled. Don Gillespie and fellow drag racing photographer Mickey McIver shot a couple of memorable photos of the forlorn tower, its windows broken by vandals and a sad plywood sign replacing the tower's front doors that read: "Yes, we are closed. It's all over."

OCIR, the ghost track

I've assembled below some photos that I think show the different sides of OCIR, some from our files and some from external sources that will give those of you who never saw it a better look and those of you who were there a nostalgic flashback.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not much of a trace is left of OCIR unless you know where to look. Using the lessons learned in my Google Earth tutorial ("Ghost-track hunting goes high tech," Oct. 17), we can plug in the coordinates provided by my friends at the ghost-track-hunting TerraTracks Global Authority and sketch the outline, as I've done below.

|

To locate the track using Google Earth, enter these coordinates into your Google Earth FlyTo box: Starting line: 33.661981, -117.74661 Finish line: 33.664994, -117.749031 End of asphalt: 33.671602, -117.75408 |

Insider reader Karl White, who works at JAE Electronics on Technology Drive, the road to the right (east) of the track in my Google Earth image, sent the photos below of the area today as well as a collection of vintage OCIR programs (bottom) for me to peruse. Thanks, Karl!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|