When it comes to 300 mph, I feel The Need: The Need To Talk about Speed

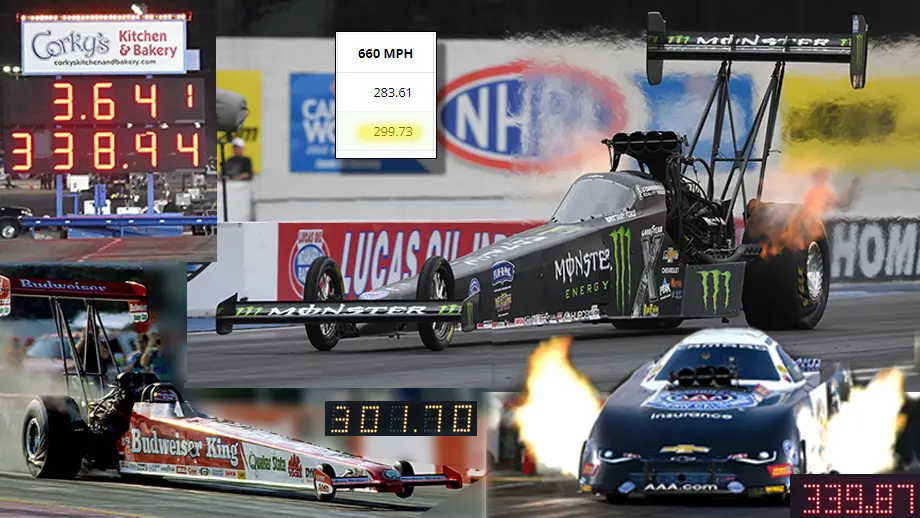

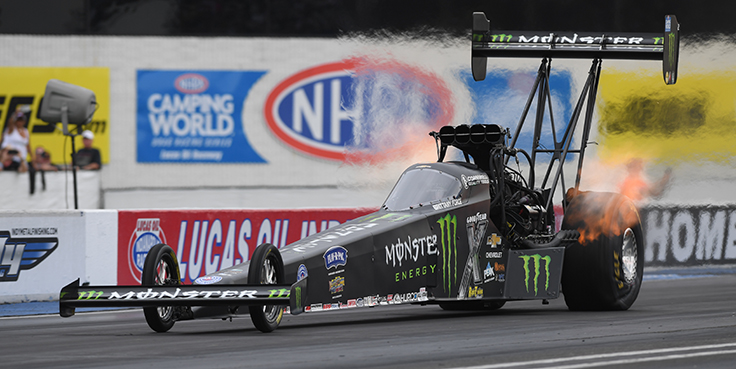

At last year’s Dodge Power Brokers NHRA U.S. Nationals, Brittany Force’s David Grubnic-tuned Monster Energy Top Fueler reached a speed of 299.73 after covering just 660 feet of racetrack, falling just shy of the magic and lucrative 300-mph speed. The first driver to reach the triple-century mark at 660 feet will collect a $30,000 payout from the Phillips Connect 300 at the 1/8 program.

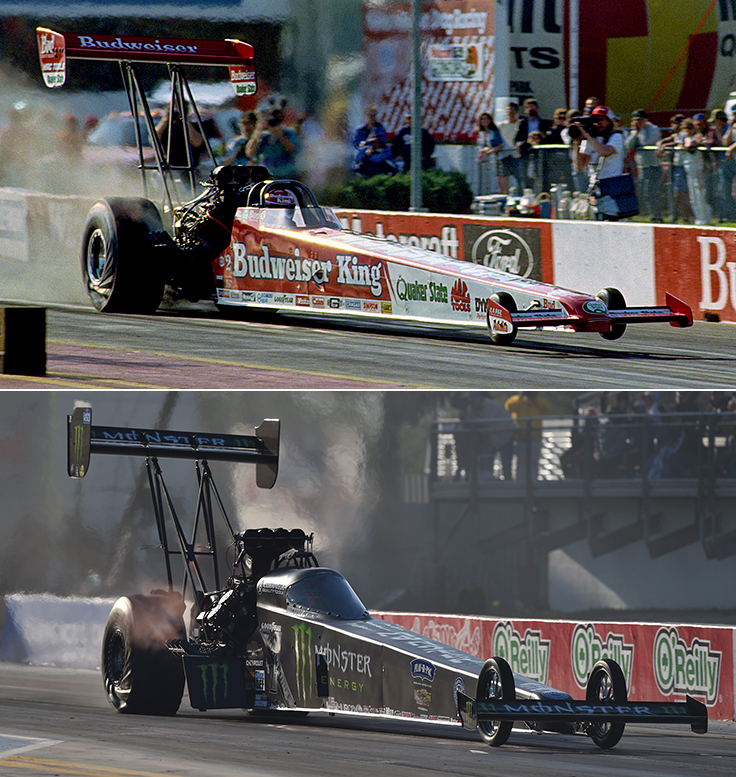

I remember not too long ago — OK, 31 years ago — when reaching 300 mph in twice the distance was an incredible feat, as Kenny Bernstein did when he broke the 300-mph barrier at the end of the Gainesville Raceway quarter-mile pass in his Budweiser King Top Fueler in March 1992.

I think the same thoughts when I see Top Alcohol Funny Cars today running 5.3-second elapsed times that nitro Funny Car drivers of the 1970s would have thought impossible without nitro in the tank. Heck, we even have Pro Mod door cars running in the mid-five-second zone with supercharged alcohol, nitrous, or turbocharged engines.

Or what about Factory Stock Showdown cars running in the 7.60s, times that 500-cid Pro Stockers — once the king of all door cars — struggled to reach until they got 500-cid engines in the 1980s?

When you compare Kenny Bernstein’s car to Brittany Force’s car, they don’t seem too different: both are 300-inch-wheelbase dragsters powered by nitromethane-fueled, supercharged 500-cid aluminum engines with direct-drive powertrains. The rear tires are basically the same. The wings are basically the same. Sure, she has a canopy, but we're told by everyone that there's no aero advantage there. He has small front tires, she has big tires. But they're both still 300-inch missiles.

So, what's the biggest difference? If you said "power," you're on the right track because we've all been taught that top speed is a result of more power. But it's not just that, according to Hall of Fame crew chief Austin Coil, who was kind enough to absorb my dumb questions last weekend. Of course, it's about power, but in Coil's mind, recently it's been more about traction and track prep than anything else.

"When Goodyear came out with a new tire about five years ago, it was a lot more of a change than anybody thought it was gonna be," he said. "Fact is, we've always had enough power to make it smoke the tires. It was more an issue of having enough traction and a smooth application to do what we knew the cars could do. When the traction is definitely better, and they have enough power to use it, that's no real mystery there."

And with today's nitro engines making 11,000 to 12,000 hp, there is a great need to either curb the power to hook it up or find a way to keep the candles lit. Another truism has always been that the more fuel you can burn, the more power you can make, which is why we started seeing dual fuel pumps and the first mega Sid Waterman pumps in the early 1980s, but then we reached the point of having too much fuel and dropped cylinders. According to Coil, today's nitro engines use fuel pumps that can supply (but not always use) 125 gallons per minute, up from about 100 gpm when he was tuning John Force back in 2010.

"The whole gig to make horsepower is how much fuel can you burn," Coil agreed. "So, the biggest thing that's happened over a long-term development is the ignition systems. When we were running a five-amp Mallory magnetos back in the 1970s, you couldn't put any more fuel in it or it would drop cylinders. Today the teams run what they call 44s, because 44 amps is the primary amperage, and they're about 600 volts, but of course, it's very intermittent. The old-time magnetos, their primary current was only 2.5 amps, and it was only about 12 to 14 volts. So's exponentially more, and, of course, they need to be."

And, of course, there's the aerodynamic factor. It took Top Fuel cars nine years to go from the first 250-mph pass (Don Garlits, 1975 World Finals) to the first 260 (Joe Amato, 1984 Gatornationals), with the most obvious change there being the introduction of the tall rear wing on Amato’s car that reduced drag while maintaining downforce.

It then took only two years to go from 260 to 270 (Garlits, 1986 Gatornationals) and two years to go from 270 to 280 (Amato, 1988 U.S. Nationals), and just one more year (!) to go from to 280 to 290 (Connie Kalitta, 1989 Winternationals), then three years to Bernstein’s 300 — an increase of 40 mph in just eight years.

Here’s a look at the generally accepted barrier-breaking speeds in drag racing history. I compiled this list from numerous sources — including an encyclopedic article that the late stats guru Chris Martin wrote for NHRA National Dragster in 1992 just before Bernstein’s run that helped me get the 150- to 290-mph facts — and it stretches outside of the NHRA (and even AHRA and IHRA), and your mileage may vary. These speeds are all recorded over a quarter-mile.

| Barrier | Driver | Date | Location | Speed |

150 |

Lloyd Scott |

Aug. 1955 |

Carpenterville, Ill. |

151.07 |

160 |

Emory Cook |

Feb. 1957 |

Wilmington, Calif. |

166.97 |

170 |

Don Garlits |

Nov. 1957 |

Brooksville, Fla. |

176.40 |

180 |

Don Garlits |

Dec. 1957 |

Brooksville, Fla. |

180.00 |

190 |

Chuck Gireth |

May 1959 |

Fremont, Calif. |

192.30 |

200 |

Chris Karamesines |

April 1960 |

Alton, Ill. |

204.54 |

210 |

Denny Milani |

May 1965 |

Sacramento, Calif. |

211.26 |

220 |

Don Cook |

April 1966 |

Fremont, Calif. |

223.32 |

230 |

Paul Sutherland |

Nov. 1966 |

Wilmington, Calif. |

230.43 |

240 |

Don Garlits |

March 1972 |

Gainesville, Fla. |

243.24 |

250 |

Don Garlits |

Oct. 1975 |

Ontario, Calif. |

250.69 |

260 |

Joe Amato |

March 1984 |

Gainesville, Fla. |

260.11 |

270 |

Don Garlits |

March 1986 |

Gainesville, Fla. |

272.56 |

280 |

Joe Amato |

Sept. 1987 |

Indianapolis |

282.13 |

290 |

Connie Kalitta |

Feb. 1989 |

Pomona, Calif. |

291.54 |

300 |

Kenny Bernstein |

March 1992 |

Gainesville, Fla. |

301.70 |

310 |

Kenny Bernstein |

Nov. 1994 |

Pomona, Calif. |

314.46 |

320 |

Cory McClenathan |

Oct. 1997 |

Ennis, Texas |

321.77 |

330 |

Tony Schumacher |

Feb. 1999 |

Chandler, Ariz. |

330.23 |

As you can see below, once the 300-mph barrier was finally breached, it took less than two years for 15 other drivers — including two Funny Car drivers — to reach the triple-century mark.

| Slick 50 300-MPH Club | |||

| Driver | Date | Venue | Speed |

Kenny Bernstein |

March 20, 1992 |

Gainesville |

301.70 |

Doug Herbert |

Feb. 13, 1993 |

Pomona |

301.60 |

Don Prudhomme |

March 6, 1993 |

Houston |

301.60 |

Scott Kalitta |

March 19, 1993 |

Gainesville |

300.30 |

Pat Austin |

April 23, 1993 |

Atlanta |

300.80 |

Joe Amato |

April 23, 1993 |

Atlanta |

300.90 |

Rance McDaniel |

April 23, 1993 |

Atlanta |

300.10 |

Eddie Hill |

Oct. 1, 1993 |

Topeka |

300.80 |

Jim Epler* |

Oct. 3, 1993 |

Topeka |

300.40 |

Del Worsham |

Oct. 3, 1993 |

Topeka |

300.20 |

Cory McClenathan |

Oct. 3, 1993 |

Topeka |

302.41 |

Ed McCulloch |

Oct. 15, 1993 |

Dallas |

301.70 |

Al Hofmann* |

Feb. 19, 1994 |

Phoenix |

301.10 |

Connie Kalitta |

Feb. 20, 1994 |

Phoenix |

300.60 |

Tommy Johnson |

March 5, 1994 |

Houston |

302.01 |

Rachelle Splatt |

March 5, 1994 |

Houston |

300.00 |

* recorded in a Funny Car |

|||

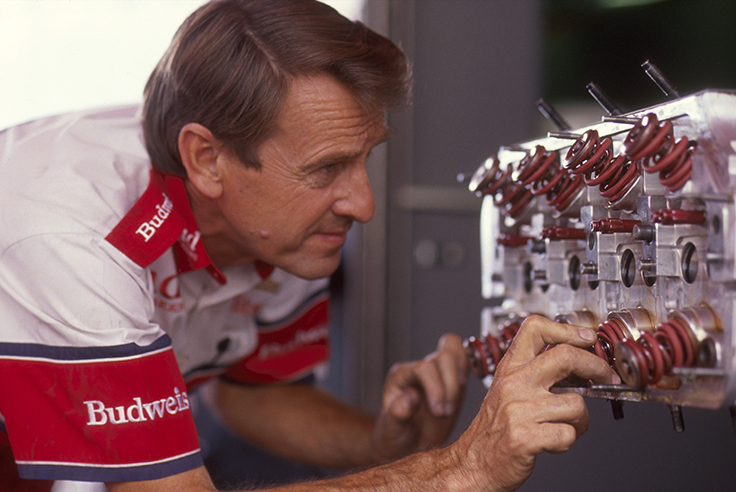

That list has some super interesting components. First, it’s crazy that Dale Armstrong (below) and the Bud King crew were so far ahead of the curve that it took almost a full year before anyone (Doug Herbert) ran 300 mph. As you can learn (remember?) in this 2012 column I wrote about the race to 300 mph, “Double A Dale” had Wes Cerny carving the heads and rare-earth magnetos to burn the fuel.

Another interesting note on this is that Herbert was the second driver to run 300 mph and the first to do it in Pomona, where his crew chief, the recently passed Jim Brissette, also tuned “Wild Bill” Alexander to the track’s first 200-mph run in 1964.

Prudhomme’s presence on the list was cool considering his trouble-plagued return to Top Fuel in 1990, and also gave “the Snake” membership in a fourth performance club after having previously graced the Cragar 5-Second Funny Car Club, the Crane Cams Funny Car 250-MPH Club, and the Cragar 4-Second (Top Fuel) Club. Rachelle Splatt was the only female in the 300-mph Club.

But back to the original premise of this column, here are the 10 fastest speeds to the eighth-mile:

| Speed | Driver | Event |

299.73 |

Brittany Force |

2022 Indy |

299.33 |

Shawn Langdon |

2022 Brainerd |

299.26 |

Brittany Force |

2019 Reading |

299.20 |

Tony Schumacher |

2018 Phoenix |

299.13 |

Antron Brown |

2017 Topeka |

299.13 |

Leah Pruett |

2018 Pomona 2 |

299.12 |

Brittany Force |

2022 Dallas |

299.00 |

Brittany Force |

2022 Brainerd |

298.87 |

Leah Pruett |

2017 Brainerd |

298.80 |

Brittany Force |

2023 Charlotte 1 |

Looking at Force’s incredible 299.73-mph blast to the eighth-mile last year in Indy, she crossed the 1,000-foot finish line timers at 337.75, meaning an increase of 38.02 mph. On her wild 338.94-mph at last year’s Finals – still the fastest speed in Top Fuel history – she was going only 297.74 and picked up 41.2 mph in the final 340 feet. Combine the last third of the Pomona run with the first part of the Indy run and you get 340.93 mph. Not that it’s that easy, but you can see the potential there.

Just as (and perhaps more) interesting was Force’s staggering 337.33-mph blast in Denver’s thin air earlier this year. Although the run wasn’t in the top 10 of all best speeds (nine of which are owned by Force), she ran just 294.31 to the eighth, meaning she picked up 43.02 mph in the final 340 feet.

Years ago, when NHRA used to allow national records to be set at altitude facilities, we had a conversion chart to factor e.t.s and speeds to their sea-level equipment (basically, e.ts got a .9xx multiplication factor and speeds got a 1.xx multiplication factor). Apparently, I threw that away long ago, so I asked Force’s crew chief, Dave Grubnic, if he had any idea what that 337-mph speed would have equated to at sea level, but it’s a tricky calculation.

On the one hand, the thin air robs the engine of horsepower, which, as we all know, is where speed comes from. On the other hand, there’s less drag in the thin air (Grubnic says it’s 24% less drag), so was it a tradeoff? No one — not even Grubnic — knows for sure, but the fact the run was seven mph faster than the incoming track record tells you what a Monster (pardon the pun) run that really was, but Coil was again happy to share his thoughts.

"That run might not have been any different at sea level," he posited, and I picture him twirling his trademark toothpick in mouth. "The air drag in Denver is so much less than it is at sea level that it's just about a wash for the horsepower. You don't really lose much horsepower in a fuel car up there because of the nitro and the blower. It does make a little less power, but there's just so much less air drag that it's just easier to go fast.

"I remember, roughly, we would raise the compression about .040 to .060, and we would spin the blower about 10% faster and put a couple of gallons less fuel in it. It would hum on down there and run about the same speeds as sea level, but not quite as quick because it took a while to start making power when he stepped on the gas. Once it got a little heated — by the time it made it to about 100 feet — it was back up to where it normally is, and once they've gotten a little ways down the tracks, the power versus drag was probably a pretty near wash. The only thing that was missing was a little in the very early part of the run because it didn't make quite as much snot when you stepped on the gas."

And, finally, here's a look at the fastest speeds in nitro-racing history; all of these are on 1,000-foot runs:

20 FASTEST RUNS IN NHRA HISTORY |

||||

1 |

Funny Car |

339.87 |

Robert Hight |

Sonoma 2017 |

2 |

Funny Car |

339.28 |

Ron Capps |

Reading 2019 |

3 |

Funny Car |

339.02 |

Robert Hight |

Reading 2017 |

4 |

Top Fuel |

338.94 |

Brittany Force |

Pomona 2 2022 |

5 |

Funny Car |

338.85 |

Matt Hagan |

Topeka 2017 |

6 |

Funny Car |

338.77 |

Matt Hagan |

Indianapolis 2017 |

7 |

Funny Car |

338.68 |

Courtney Force |

Topeka 2017 |

8t |

Funny Car |

338.60 |

Robert Hight |

St. Louis 2017 |

|

|

Funny Car |

338.60 |

Robert Hight |

Dallas 2017 |

10 |

Top Fuel |

338.43 |

Brittany Force |

St. Louis 2022 |

11 |

Top Fuel |

338.26 |

Mike Salinas |

Brainerd 2023 |

12 |

Top Fuel |

338.17 |

Brittany Force |

Las Vegas 2 2019 |

13 |

Funny Car |

338.09 |

Robert Hight |

Topeka 2017 |

14 |

Funny Car |

338.02 |

Matt Hagan |

Dallas 2022 |

15 |

Top Fuel |

338.00 |

Brittany Force |

Las Vegas 1 2022 |

16 |

Top Fuel |

337.92 |

Brittany Force |

Phoenix 2020 |

17t |

Top Fuel |

337.75 |

Brittany Force |

Gainesville 2022 |

|

|

Top Fuel |

337.75 |

Brittany Force |

Sonoma 2022 |

|

|

Top Fuel |

337.75 |

Brittany Force |

Indy 2022 |

20t |

Top Fuel |

337.66 |

Brittany Force |

Reading 2022 |

|

|

Top Fuel |

337.66 |

Brittany Force |

St. Louis 2021 |

As you can see, as fast as Brittany Force has been in her dragster, top speed of the NHRA world still resides in the Funny Car category, where eight of the fastest runs in history were made by fuel coupes, and Mike Salinas' stout 338-mph Top Fuel blast last weekend in Brainerd was the third quickest in class history, but doesn't even make the top 10 of all-time runs.

Those Funny Car runs were almost exclusively made in the 2017 season under different rules. Robert Hight tickled the 340-mph barrier in Sonoma with a rocketship blast of 339.87 in the special-edition California Highway Patrol Camaro (can you imagine a CHP officer seeing that on his radar gun?) and, a few months later, ran 339.02 in Reading. Both of those runs were made in the laid-back header days — when crew chiefs tilted their headers back to get more thrust than downforce — but Ron Capps’ stunning 339.28-mph pass, the second fastest in history, was recorded in Reading in 2019 after a rule against severely laid-back headers was instituted for the 2018 season.

Hight’s eighth-mile speed on his 339.87 in Sonoma was 292.27, meaning he picked up a staggering 47.6 mph in the last 340 feet, but his 339.02 was a stunning increase of almost 51 mph over the eighth-mile speed of just 288.03.

Incredibly, Capps’ 339.02 was even better, picking up a jaw-dropping 53.19 mph from 660 feet to the finish line.

I asked Capps, fresh off of his milestone 75th career win in Brainerd, about his 339 being the outlier of that dataset, both in increased speed and without laid-back headers.

"You have to remember that at the time, [crew chief Rahn] Tobler was still running the five-disc clutch,” he remembered. “He had looked back at his notes from the year before when we were just so underpowered, and he just threw everything at it the first lap on Friday afternoon, and we set a track record [3.84 at just 329 mph]; it already hauled ass that first run because he just tried to lock up the clutch as soon as he could. It was literally pulling the front end off the ground when the clutch locked up, and I was just hanging on to it.

“Reading is such a tricky place because it's usually got teeth, and if you don't hit it right the first lap, you're chasing yourself, but making that good first run set up the second run.

“That night we got delayed a little bit to where it got to be dark. Tobler just said, ‘Hang on,’ and threw even more at it. I just remember the front end was so light, and it was trying to haul the mail, and I was just trying to hang on to it. The back half was incredible. When it lifts up the front end up like that, you can't see over the injector because if the injector goes up one inch, that takes away a lot of your view, believe it or not.

“With that five-disc, the clutch literally welds together, and it's like another gear. Rarely does a track hold it because it really jars the driveshaft, but when you hit it right, like we did on that run, it just lifts up and takes off because the clutch was 1:1. I knew [it] was on a good run. I didn't know it was that good. I knew when I hit the chutes and it about threw me out of the car as hard as it's ever done, so I knew then that it was good.”

Good and then some.

The other problem with laid-back headers, which was evident just watching those cars in 2017, was that taking away the header downforce in favor of rear-facing thrust made the cars almost undrivable with the front tires dancing on the track or, in Cruz Pedregon's case at Las Vegas in the fall of 2016, even worse.

"The fact that the cars weren't built with that in mind, was certainly a factor in that rules change, but another factor that made it easy to change is that the car owners all got pretty tired of replacing the bodies and the wraps because the sides were burned off them." (I think he is joking. Maybe not.)

Capps NAPA entry always seemed to be among the most affected by the scorching, which you wouldn't expect with headers pointed more back than up, but, again, Dr. Coil had the answer: It was the Coandă effect at work. The theory, as developed by Romanian inventor and aerodynamics pioneer Henri Coandă and explained to Coil by the brilliant Ron Armstrong, explains that one airstream is going to try to join another if they're close enough together.

"Even though the exhaust was pointed out to the side pretty good, the airstream going around the body pulled the exhaust in," Coil explained. "Capps' car had headers that were laid out to the side more than everybody else's, but it still burned the paint just as bad. The Coandă-affected area didn't give a damn which way it was pointed. It would pull it in and burn the side of the car."

So, there you have it, folks, a history of speed through the years AND a little physics lesson. Will someone go 300 to the eighth-mile in Indy? With five qualifying sessions, I'm betting yes. We only have to wait a week to find out.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator