A look back at some thrilling winner-take-all championship-winning final rounds

Drag racing, by its very nature, is a series of single-elimination contests. Win and move on to the next round; lose and go home. But what about when there is no next round, when the final round is the final round of the season, and the two finalists are in a winner-take-all battle for the world championship?

It’s only happened five times in NHRA Professional-class racing, the most recent being last weekend’s thriller in Pomona when Doug Kalitta and Leah Pruett staged up with the winner earning a first career world championship. It doesn’t get a whole lot more dramatic than that, but the Kalitta-Pruett duel for the crown was the second time it’s happened in Top Fuel and the fourth time it’s happened at the track now known as In-N-Out Burger Pomona Dragstrip.

Let’s take a trip back into history to look at these fantastic finales.

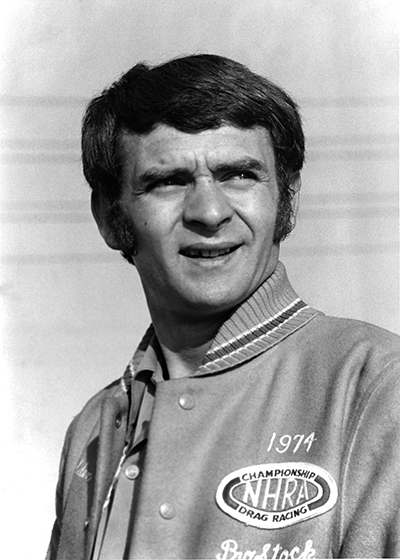

1974: Bob Glidden vs. Wayne Gapp

The battleground was famed Ontario Motor Speedway for what ended up being a three-way shootout between incoming points leader Wally Booth, Wayne Gapp, and Bob Glidden.

Booth entered the World Finals with the points lead but holding just a 47-point edge over Gapp. Booth’s AMC Hornet had defeated Gapp’s four-door Ford Maverick in the final round earlier that year to win the Gatornationals, while Gapp had defeated Glidden to win Le Grandnational in Montreal.

Behind the wheel of his Pinto, Glidden had won the Columbus Springnationals, but trailed Booth by a whopping 330 points and behind Gapp by a gap of 283 markers.

Let’s stop right here on that point. Today, a 330-point lead is a hammerlock on the championship, but back then, each round-win was worth 200 points, and you could also get 200 points for resetting the national record as well as 25 points each for low e.t. and top speed of the meet.

Regardless, Glidden came into the Wold Finals needing some magic and got it early when he reset his own national record, from an 8.83 set earlier in the season at the Beech Bend divisional event (and back then points totals for the Pros were a combination of national and divisional events, just as it is for today’s Sportsman racers) to an 8.81 to earn a provisional 200 points, assuming it wasn’t bettered by someone else later in the event.

All three survived round one, but Booth’s Hornet broke in round two against Don Nicholson, and two pairs later, Bobby Yowell red-lighted to Gapp to give Gapp the points lead. Glidden had beaten Roy Hill in round two then beat Nicholson in the first pair of the semifinals to momentarily take the points lead, but Gapp then got a bye run when Ken Dondero was unable to make the semifinal call and took the lead back.

The final round would decide the championship, but with Gapp’s lead at just 82 points, it could have gone a myriad of ways, including an improbable scenario in which Gapp could have lost the race and still won the championship if he broke Glidden’s record with an 8.80 or better – he already had an 8.84 backup ready from qualifying – losing on a holeshot but winning the championship.

Here’s what could have happened:

- Gapp could beat Glidden and win the championship by 282 points.

- Glidden could beat Gapp and win the championship by 118 points, or 143 or 168 points if he held onto either or both low e.t. and top speed points as well.

- Glidden could beat Gapp on a holeshot, but Gapp could lose the round on a national-record-setting holeshot pass and win the championship by 132 points (taking away Glidden’s 200 national record points and 50 low e.t. and top speed points).

Fortunately for the stats keepers and numbers crunchers, none of that happened as Glidden won his first of 10 championships, 8.89 to 8.91. Glidden did have a bit of a fright as his car spun the tires at the launch after water from a shortened burnout procedure – he thought he might have broken something and didn’t make a dry hop – stayed on the tires. He was able to track Gapp down in the last few feet with a speed of 153.84 mph to Gapp’s 151-flat, a speed Gapp attributed to a flagging engine. Glidden won the championship by 168 points.

1990: Joe Amato vs. Gary Ormsby

Almost since his debut in Top Fuel, Joe Amato, with crew chief Tim Richards, was a serious player. In 1983, just their second full season, they finished second behind Gary Beck, and the following year they won their first of five titles over the next two decades. Ormsby had returned to Top Fuel in mid-1983, but his Lee Beard-tuned Castrol GTX mount didn’t really come to life until 1989, when he won six times en route to nosing out Amato for the championship.

Amato and Ormsby dominated 1990, with each winning six times (on a 19-race schedule), and the championship came down to the final round in Pomona.

Ormsby entered the World Finals trailing Amato by 254 points, but by setting low e.t. (with a 5.01, then worth 50 points) and qualifying ahead of him by two positions (No. 1 to No. 3, for four more points), he was exactly 200 points (or one round-win) behind Amato going into eliminations.

Amato, who had defeated Ormsby, 4.96 to 5.09, in Saturday's $50,000-to-win Top Fuel Classic final, was steadily consistent Sunday with runs of 5.02, 5.02, and 5.03 for wins over Wayne Bailey, Eddie Hill, and Gene Snow. Ormsby was in the five-teens in trailering Jim Head and Don Prudhomme but earned lane choice for the race of his life with a 5.02 to 5.09 semifinal win against Kenny Bernstein. With a final-round win over Amato, he could tie him to the point. It was the perfect storm.

Ormsby staged last and left first … but too soon. G.O. red-lighted, but it probably didn't matter as his green and white machine quickly went up in smoke. Amato went right down the track and, to add insult to injury, bettered Ormsby's low e.t with a track-record 4.93. The final points tally, 16,058 to 15,558, didn’t reflect the closeness of the battle, but Amato still left Pomona with his third championship, tying him with Don Garlits and Shirley Muldowney.

I tracked down "Joe Cool," who's been globe-trotting the last few years enjoying his retirement years, to get his memories of that magical moment.

"That was the most pressure I ever had," he admitted. "To win the race to win the championship. We had won the big-bucks shootout the day before, so there was like 250,000 bucks on the table for bonus money plus all the bonus money I got with Valvoline at the time, so it was a big deal above and beyond the championship itself.

"To be honest, I didn't know he red-lighted; I just thought he might have jumped me, and for that millisecond, I thought, 'Uh oh,' but then he fell back pretty quick when he smoked the tires, so then you just want to keep it between the guardrail and the centerline and get it down through there, because it's not over till it's over.

"I remember Gary going to his van and pulling out a cigarette. He congratulated me, but I'm sure he felt bad. I was elated because I won, but I still felt bad for him because somebody has to win and somebody has to lose. I think the fact that he wasn't going to win the race anyway after smoking the tires made him feel a bit better about the red-light.

"Pressure does funny things to people whether you're racing for a world championship or trying to make a putt on a golf course for a $10 bet. One thing I think that helped me a lot was that I always had a lot of business dealings that I dealt with away from the track, so I was used to pressure that way. Having a large business and the mindset of what I'm dealing with all the time helped me handle that kind of pressure."

Ormsby, sadly, is no longer with us to share those emotions, but I exchanged emails with Chuck Schifksy, who along with the still-wrenching and still-winning Mike Green were part of Ormsby's crew back then, for his recollections. Schifsky, who after his wrenching days ended went into the publishing world and worked closely with my lifetime best friend C. Van Tune at Motor Trend before moving to his current position as manager of Honda & Acura Motorsports, remembers that year well.

"The combination of that 300-inch chassis and our fuel and clutch setup gave us a big jump in performance coming into 1989 that we carried through to 1990," said Schifsky, pictured above, left, with Green. "Amato had the same Al Swindahl chassis, and obviously, he had Tim Richard’s tuneup, which seemed to only get better coming into the Winston Finals. We struggled a bit in qualifying, even though we qualified No. 1. We had some mechanical problems that we never did really understand the cause of. Because we had low e.t. up to that point, and that paid 50 points, we were exactly 200 points, or one round, behind Amato going into eliminations. We made it through round one and beat 'Snake' in round two, but Amato was running quicker than us.

"For the semifinal race against Bernstein, we made a pretty big clutch change, and it paid off with a 5.02. As the sun went down, and it got cooler, as it typically does at Pomona, the track got better, and we got even more aggressive for the final-round race with Amato. We originally were going to take the left lane, but Bruce Larson smoked the tires at half-track and lost to Ed McCulloch in the Funny Car final in front of us, so our crew chief Lee Beard decided that we should swap lanes and take the right lane.

"None of that mattered as Ormsby left too early, and shortly thereafter, our Castrol car went up in smoke. For us, it was all very anti-climatic. The entire year, battling back and forth with Amato, came down to that unsuccessful final round – red-light and tire smoke.

"A couple of days after the Finals, Mike Green, Don Loveless, and I informed Ormsby that we would be leaving his team to go to work for Jack Clark and build a new team around driver Tom McEwen. What we didn’t know at the time, was that a few short months later Gary would announce that he was battling cancer and ultimately lose that fight shortly after. Many of us believe that Gary knew he had cancer during that Pomona Finals weekend, which makes that loss even more profound."

2007: Matt Smith vs. Chip Ellis

Following a semifinal loss at the season’s penultimate race in Las Vegas, Matt Smith was prepared to concede the 2007 Pro Stock Motorcycle title to Andrew Hines, who entered the World Finals in Pomona with a 39-point cushion in the standings. Hines had a chance to make history in Pro Stock Motorcycle as the first rider to win four straight championships, but he staged his points-leading Harley too shallow in the second round and drew a foul start against Antron Brown's U.S. Army Suzuki.

Smith saw an opportunity and capitalized on it.

Smith and Chip Ellis then began the long climb to reach the final round that either of them needed to surpass Hines, and in improbable fashion, both did, setting up a winner-take-all final.

“After Las Vegas, I thought my hopes were gone,” Smith said. “My goal was to win Pomona, and I thought if I did that, I would probably finish second to Andrew. I was at the scales when the NHRA tech crew told me that Andrew lost, and all of a sudden I was back in it. I knew we had Antron Brown in the semifinals, and I thought I could beat him. Then, I had to worry about racing Chip in the final, but I really thought our bike was as good as anyone else’s.”

Smith's Torco Buell raced to a 6.94 to 6.95 victory to earn him his first championship. Hines finished second, Ellis third.

“I never expected to be there, but once we got to the final, I knew that it was do or die,” said Smith. “I just focused on doing the same things I’d been doing all day. I’ve been cutting good lights all year, and I just wanted to have one more and then let the bike do its thing. I knew that Chip was fast, but I knew that I was fast, too.

“At half-track, I was tempted to look over, but I didn’t,” said Smith. “I didn’t know who was ahead, and I didn’t want to know. I just stayed tucked and waited for the finish line. When the win light finally came on in my lane, I can’t explain the feeling. It was a mixture of excitement, relief, and a lot of tears.”

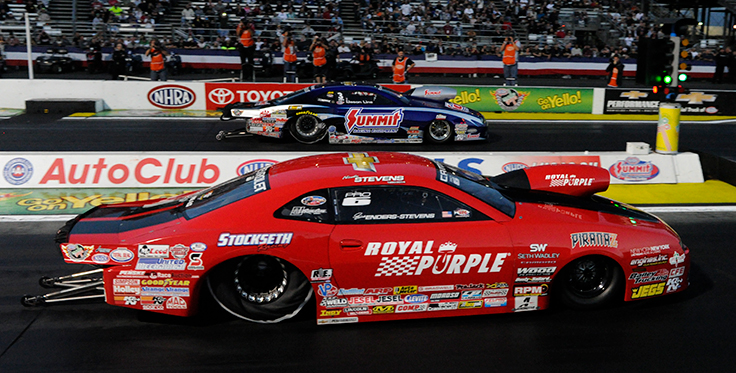

2014: Erica Enders vs. Jason Line

Erica Enders' Pro Stock victory at the 2014 Finals made her just the third woman — behind Shirley Muldowney and Angelle Sampey — to win an NHRA Pro-class championship, but she and her Elite Motorsports team had to work for it. Jason Line qualified No. 1 and earned enough points to keep her lead at 19 points, or less than a round of racing, setting up what seemed to everyone to be an inevitable and deserving final-round showdown between the two Camaro drivers.

Enders’ red Chevy made an amazing three straight 6.494-second clockings in the preliminary rounds, the last of which, against Jonathan Gray in the semifinals, was coupled to a perfect reaction time. Incredibly, Gray also had a perfect light — the first time in NHRA history that had happened — but his 6.524 fell well short of her pace.

Line had followed a first-round 6.49 of his own with two 6.51s and probably felt he needed an edge at the Tree to win the race and the championship but left .011-second too soon, just .009-second ahead of Enders, whose own -.002 red-light otherwise would have been a heartbreaker for her.

“It all boiled down to the last round at the last race of the year, with everything on the line against one of the baddest guys in the class, and we were able to get it done,” said Enders, who won the title by 39 points. “I felt clean on the Tree when I let the clutch out, but he was out in front of me. I was thinking, ‘There’s no way he cracked me on the starting line.’ When I plugged it into high gear and checked up, I saw where he was at, and then when I focused back on the finish line to keep the car in the groove, I did see that little yellow light on the guardwall past the finish line glowing. I’m sure I started screaming.”

2023: Doug Kalitta vs. Leah Pruett

Steve Torrence came into the final race day of the season with a slim points lead of just 12 points on Doug Kalitta and 39 points over Leah Pruett, and all three reached the semifinals, along with Justin Ashley.

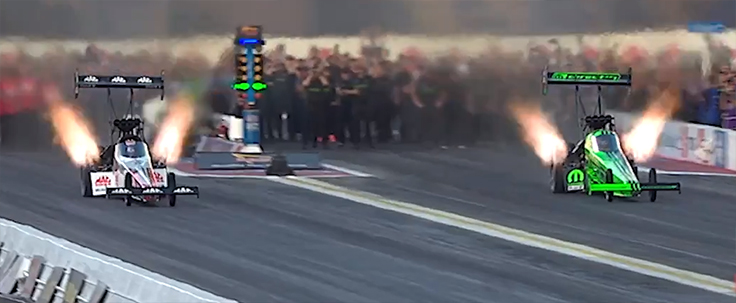

Kalitta put away Ashley with a 3.728 and then jaws dropped all around the Pomona track when Pruett ended Torrence’s bid for a fifth world championship, 3.717 to 3.765, ensuring that we’d not only have a new first-time Top Fuel champ but that it would be decided in the final round. With Kalitta’s lead at just 27 points and 30 points awarded per round-win at the Finals, it could go either way.

Kalitta had been marginally quicker than Pruett on the Tree in each of the three preceding rounds and was again in the final with a sterling .047 against her competitive .065, and his Mac Tools car pulled away at every distance between there and the finish line to win by a comfortable six-hundredths of a second to finally give the six-time title runner-up his first world championship.

As I watched Kalitta on stage accepting the well wishes of the crowd, I spied Tony Schumacher standing by watching Kalitta’s coronation and couldn’t help but think back to 2006’s “The Run,” where Schumacher entered the season finale deep in the points hole but clawed and scratched his way into contention. All Kalitta had needed back then was to reach the final to lock up the title, but Melanie Troxel beat Kalitta on a semifinal holeshot, 4.502 to 4.500, using her best reaction time of the year, an .026, to score her only holeshot win of the season.

The stage was set, and Schumacher not only needed to beat Troxel in the final but reset his own 4.437 national record to get the bonus points to pass Kalitta. The problem facing Schumacher and his tuner Alan Johnson – oh, my, the same Alan Johnson now tuning for Kalitta this year? – was that they had to run 4.436 or better but not quicker than 4.414, which would have been too quick to be backed up by Schumacher’s previous best at the event, a 4.458 from qualifying.

Johnson tuned Schumacher’s Army dragster right into that narrow window, turning on the win light with a 4.428 and earning Schumacher the championship. The crestfallen look on the face of Kalitta, who stood at the top end awaiting the outcome, speaks volumes. Who knew it would take 17 years to erase that curse?

Ironically, Kalitta also won this year’s championship from the right lane against a female opponent, and as I stood there with Schumacher taking in the spectacle, I asked him, “Do you think he can now finally forget 2006?”

He looked at me, grinned, and said, “The replay of ['The Run'] has been playing all weekend [on the event big screens]. I wouldn’t have put Alan Johnson back in the right lane at Pomona with the championship on the line.”

I’m not one to second-guess anyone, let alone a championship-capable team. Even though Pruett’s team had not run the left lane since the first round and had won the semifinals in the right, they had also barely escaped traction woes in the right lane in round two and, with final-round lane choice, opted to go back to the left lane, where they had made their best run (3.708) and possibly because Kalitta had not run the right lane all day. Maybe for all three reasons.

Kalitta’s win resonated around the drag racing world. My buddy Al Kean — he of the famous 1971 “Snake”-on-fire Seattle top-end photo — sent me an email lamenting his decision not to attend.

“I've been hoping for Kalitta to win the championship for 20 years, and it is so nice to see him finally do it!” he said. “I even shed a tear or two. My friend in Seattle also said he shed tears when Kalitta won. This guy is the real bona fide sentimental favorite!”

And Amato, still a fervent fan who catches all of the television shows, added, "I like Leah, but Doug has paid his dues. With so many young kids out there who have been knocking it dead, it's nice to see one of the old guard win it, and especially for Connie while he's still here, healthy, wealthy, and wise. When I look at all the comments on the internet, I think the whole world is really happy that Doug won."

For Pruett and crew chief Neal Strausbaugh and the whole TSR team, I have nothing but the largest amount of adoration and admiration for how far they’ve come in just two years. I expect that Pomona 2023 won’t be their Kalitta 2006 cross to bear for long and the graciousness with which she handled the defeat, as personified in this congratulatory photo by NHRA National Dragster’s own Jerry Foss, makes her a champion in every other way in my book.

The winner-take-all final round was a fitting coda to a wild and thrilling season and just makes everyone even more ready for the 2024 season to get here.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator