Chevy's COPO supercar: The 427 ZL1 supermodel stocker next door

“Looks like a 200-pound Marilyn Monroe.”

—Smokey Yunick, on first seeing Chevrolet’s all-iron 427-cid “Mystery Motor” in 1963

In a Detroit conference room in 1963, racing legend Smokey Yunick stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Chevrolet icons—Ed Cole, Bunkie Knudsen, Zora Arkus-Duntov, and a nearly unknown engine designer named Richard “Dick” Keineth. It was 7 a.m., and they were viewing a disassembled 427-cubic-inch “Mystery Motor,” Chevrolet’s next-generation big-block prototype. It was sleek. It was powerful. It had a sexy new valvetrain. But Smokey wasn’t sold.

“Looks like a 200-pound Marilyn Monroe,” he jabbed. Good looking—but too heavy.

The engine that laid before them marked the dawn of the Chevrolet big-block—a turning point in American motorsports and the beginning of the Bowtie’s relentless pursuit of a factory racing engines for NASCAR and NHRA. In his 2001 memoir, Yunick would go on to call Dick Keineth “the best engine man Detroit ever had.” Six decades of big-block dominance have proven Yunick wasn’t wrong about Keineth.

That same bloodline of engineering would eventually give us the 427-cid ZL1—Chevrolet’s most advanced and exotic aluminum block and head production big-block.

Today, more than 60 years later, an homage to those rare machines has come back with a vengeance to turn on win lights in the NHRA competition.

The Memo That Started It All

A few months before Yunick’s now-famous remark, Chevrolet circulated an internal memo titled 1963 Performance Program NASCAR & Drags, dated August 21, 1962. Issued by Vince Piggins, head of Chevy’s Economy, Safety, and Performance Department, it was addressed to top engineers including Arkus-Duntov, D.H. Macpherson, and Dick Keinath. Its directive? Build two new 427-cubic-inch engines for the upcoming racing season.

Chevrolet was going after Pontiac’s 421-cid Super Duty crown.

Ten engines were to be completed in time for the 1963 Daytona Speed Weeks. These would become the now-legendary Mystery Motors—early 427s using porcupine heads and a stroked crank stuffed into a reworked 409 block to create 427 cubes.

The memo also laid out an ambitious drag racing plan: under the “Drag Activity” header, Chevrolet would produce 50 lightweight 1963 Impalas with aluminum front sheet metal and W-head-based 427-cid engines, all assembled at the Tonawanda Engine Plant in New York.

This bold era of behind-the-scenes experimentation gave rise to the Mark IV big-block family—and ultimately, its crown jewel: the ZL1.

The ZL-1: Chevrolet’s Exotic Aluminum Assassin

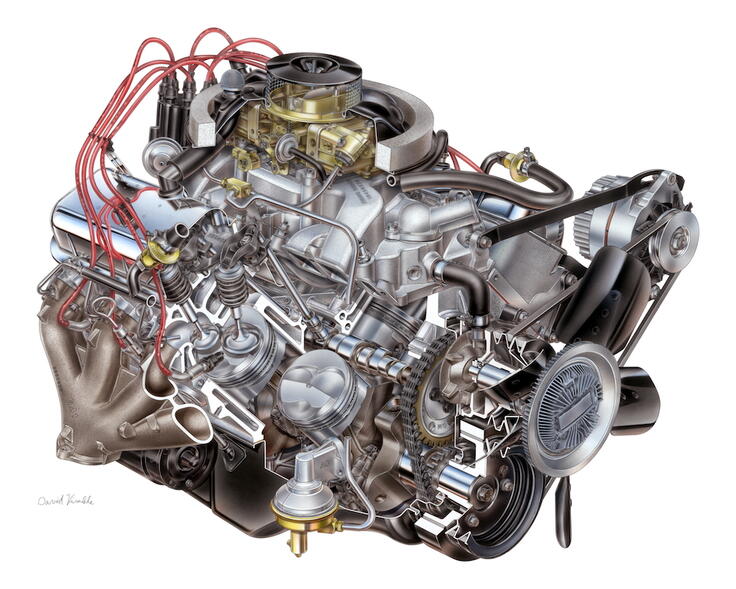

By 1969, Chevrolet had taken its 427-cid design to the outer edge. The ZL1 big-block was based on the brutal L88 427-cid engine, but replaced its cast-iron block with aluminum, cutting weight and improving thermal performance. With 12:1 forged pistons, 2.19/1.88-inch valves, a Holley 850-cfm carb atop a high-rise intake, and a .560/.600-inch lift camshaft, the ZL1 was essentially a Can-Am engine in a Camaro.

Only 69 Camaros and two Corvettes received ZL1 427 engines. Each was hand-assembled in a climate-controlled room at Tonawanda, broken in on a dyno, and often delivered making 505–535 horsepower—well above the factory rating of 430 hp.

It was overkill. It was brilliant. It was expensive. And it was fast. The ZL1 engine option doubled the cost of a Corvette or Camaro and transformed them into supercars.

Enter: The McClanahans and their 427

Fast forward to the early 2000s at Los Angeles County Raceway (LACR) Dragstrip. Sitting quietly in the dirt was a brown 1969 Camaro, nearly forgotten. The McClanahans, who called it “Brown Beauty,” said it was once owned by the track owner Bernie Longjohn’s daughter—but life got busy, and the car was left behind.

In 2004, the McClanahan family brought it home. What others saw as a sun-baked relic, they saw time machine. Over the next few years, they rebuilt the car with care and precision, prepping it for NHRA Stock Eliminator AA/SA competition with an iron-block 427.

It debuted at the 2010 Firebird Divisional race, finishing runner-up at that year’s Winternationals. In 2018, Brian McClanahan drove it to the NHRA Stock Eliminator World Championship title. Then in 2020, it edged out a Ford Thunderbolt in a heads-up final to win the Winternationals once again. That was the year that COVID-19 hijacked many drag racing plans, and the AA/SA Camaro was parked while the family’s Cobalt raced on.

2025: The ZL-1 Marylin

The ZL1 engine powering the McClanahan family’s Camaro is a modern throwback to Chevrolet’s 1969 COPO legacy—an all-aluminum powerhouse built by none other than Jason Line. Final dyno testing took place on the Friday before the 2025 NHRA Winternationals, and by Sunday, the engine had made the coast-to-coast journey from North Carolina to California. Now that’s Pro Stock delivery pace.

This is the first all-aluminum ZL1 unleashed on NHRA Stock Eliminator racing in years, as aluminum blocks have been nearly impossible to source. In the meantime, NHRA rules allowed iron blocks, but the introduction of the J Line T-357 block changes the game. Weighing just 130 pounds—roughly 155 pounds lighter than the cast-iron alternative—this block brings back the original weight advantage the ZL1 was meant to deliver.

According to Line, there's no performance degradation at this power level despite the aluminum foundation. The block features steel cylinder liners and steel main caps, with NHRA rules permitting modest increases to bore and stroke—specs this engine fully utilizes. Up top are Chevrolet Performance open-chamber ZL1 spec heads, and inside, a camshaft with .580-inch intake and .620-inch exhaust lift, paired with modified duration and lobe separation. Jesel aluminum roller rockers ride on the stock style studs, and the rotating assembly includes steel connecting rods, forged aluminum pistons, and a compression ratio just north of 12:1. With trap speeds suggesting output in the 700-horsepower range and a tach redline revealing engine speeds above 8,000 rpm, this ZL1 isn’t just a tribute to the past—it’s the foundation for a new wave, with at least five more J Line aluminum-block builds on the way.

On the car’s first four runs with the new ZL1 spec engine, it recorded the three quickest passes of its life.

The McClanahans have dialed in the setup to the thousandth. At the 3,285-lb minimum weight, the ZL1 Camaro launches with 24° of ignition timing, ramping up to 40° downtrack. It’s backed by a TH350 transmission and a 12-bolt rear with a custom gearset, connected to a leaf-sprung suspension refined over decades.

A Legacy with No Expiration Date

With more than 200 passes a year, the Summit white ZL1 Camaro is more than a race car—it’s a full-time member of the McClanahan family. It’s been driven by Brian, now Ryan, and one day—maybe—by 4-year-old Declan McClanahan, who watched this weekend from the starting line, just shy of his fifth birthday.

This Camaro isn’t just a machine. It’s a legacy in steel and aluminum, one to be handed down like a family heirloom.

The COPO Spirit Lives On

The 1969 Camaro ZL1 wasn’t meant to be practical. It wasn’t built for comfort. It wasn't built to catch your eye. It was born to race, and very few still do. But the McClanahan’s ZL1, she’s back out here, launching hard, grabbing gears, and collecting win lights. And somewhere, you can bet Smokey Yunick is smiling—not because the Rat Motor makes a lot of power—but because Jason Line took what looked like a 200-pound Marilyn Monroe and turned her into a full-throttle knockout.