To heroes lost ...

It’s been a rough couple of weeks for longtime racing fans (and especially Funny Car fans) with a number of passings of some more of our heroes: Hayden Proffitt, Judy Lilly, Gabby Bleeker, Russell Long, and Bill Schultz.

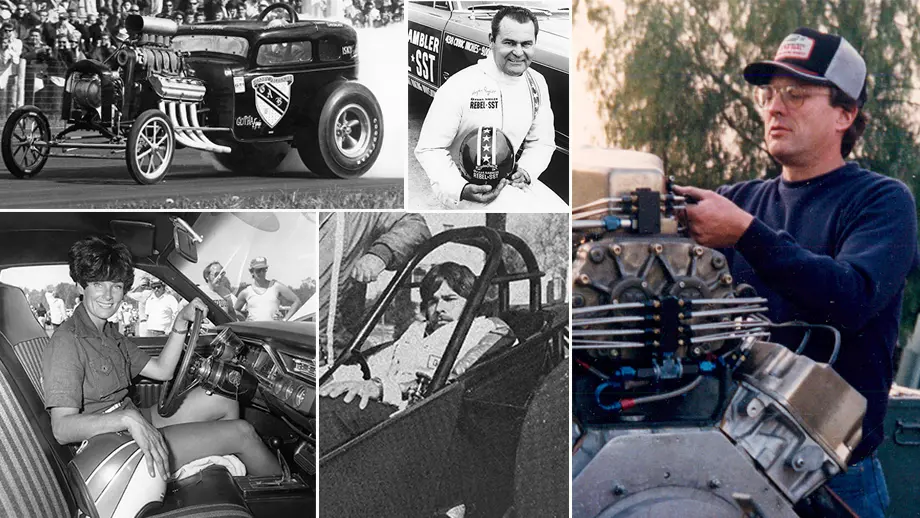

Depending on your entry into drag racing fandom, Schultz may have meant many things to you. If you fell in love with the sport in the 1960s, you probably remember him as the king of Top Gas dragster tuning. If you’re a ‘70s fan, you’ll remember him being the crew chief genius of the Over the Hill Gang Top Fueler. If you’re from the ‘80s and ‘90s, you’ll probably remember him as a national event-winning Funny Car tuner for the likes of Tom McEwen, Mark Oswald, Dale Pulde, Al Segrini, and others.

"We've won national events with just about every driver we've had," Schultz told NHRA National Dragster back in the mid-1990s, "and we're proud to have won national events in four decades. l guess you could say that's our greatest accomplishment. Being able to stay current and compete for that long tells us that maybe we know a little something about what we're doing.

"I’ve always had the pleasure of having some of the very best drivers in the class. Guys who were conscientious and saved parts for us. I have a lot of good memories of things, but a lot of them have to do with little local races in Southern California."

Schultz, who passed away Aug. 29 of a massive heart attack at age 85, grew up in Southern California during drag racing's infancy and, in a funny yet dubious tale, once told us that his introduction to drag racing was accidental.

“It was back in 1953, while waiting at the train station with my folks,” he shared in 1979. “I went over to buy a magazine, but the seller wouldn’t sell me any of the girlie magazines, forcing me to settle for Hot Rod magazine.”

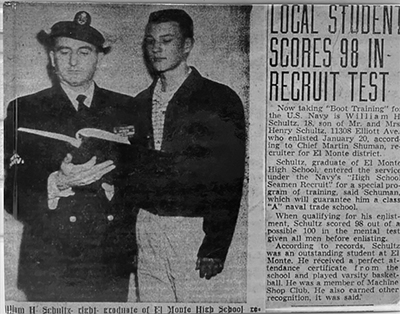

Although he’ll be best remembered for his wrench work, Schultz actually drove, racing at Southern California tracks like San Gabriel, Pomona, and Colton in an E/Gas ’39 Chevy before entering the Navy for four years. He recorded the highest mental exam score (98 out of 100) that the Navy had ever seen at that time. During his service, he worked to keep his ships' mechanical parts working, and in his spare time, he built parts for race cars in the ships’ machine shops, which he mailed home.

After his service, Schultz earned a Bachelor of Science degree in mathematics while minoring in philosophy. It was during college that he met Jerry Estep, with whom he partnered on a B/Roadster and then a Ford-powered gasser. Before long, his mechanical prowess led to the lead role in 1965 of tuning the blown Olds-powered Carpenter & McCramer machine, one of the quickest of the breed.

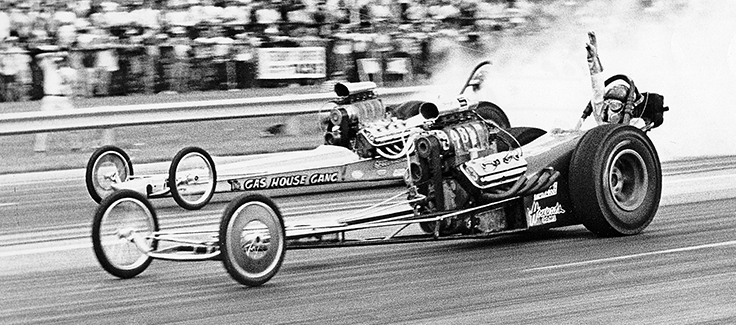

Schultz and Estep took the Olds combo to a dragster in 1966, and in 1967, he partnered with Jack Jones on a Top Gas dragster that would bring them both fame, including a win at the 1968 Nationals (pictured) and the 1969 Springnationals in Dallas, but broke up for a short time, with Rick Ramsey taking over the wheel.

Schultz stepped up again in 1970, partnering with Gerry Glenn on a Top Fuel car that tore up the town for the better part of two seasons.

"I think we held the strip record at Long Beach, Orange County, and Irwindale all at the same time with the Schultz & Glenn car,” said Schultz. “That was an accomplishment in and of itself because, at that time, we were battling with some of the baddest guys in the class.”

Schultz retired from racing in 1972 but returned five years later.

"We didn't have any sponsor help at the time, and with the advent of aluminum motors and escalating budgets, we decided to quit," said Schultz. "Mike Demerest and I had our own engine shop for quite a while, and I really didn't do anything until 1977, when the late Jim Thomas with Genuine Suspension came around and wanted to build a Top Fuel dragster."

After seven years away, a lot of doubters existed as to whether Schultz could resume his winning ways. He partnered with Thomas and driver Gary Read, and they initially struggled but soon found their footing.

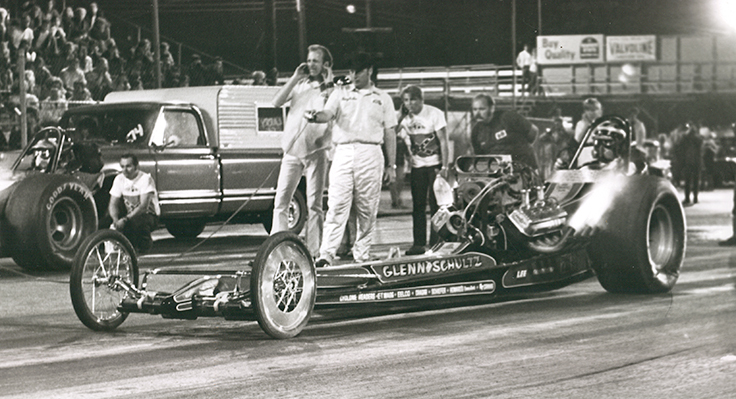

”They said, ‘You've been away too long: you probably can't do it,’ so we decided to call ourselves the ‘Over the Hill Gang.’ Basically, it was a group of my buddies, some I knew from high school and others that I had met through drag racing."

In 1979, Schultz wrenched the Kelly Brown-driven Hill Gang Top Fueler to a record-tying four wins in nine NHRA national events, including the 25th anniversary U.S. Nationals, and finished second to Rob Bruins in the points standings.

In 1980, Schultz went to work for Kenny Bernstein, then had stints with John Collins, John Force, Tripp Shumake, Segrini, Pulde, and McEwen before beginning a long association with In-N-Out Burger in 1987.

In 1988, Pulde drove Schultz's Firenza to victory at the season-opening Winternationals. After the Candies & Hughes team retired from racing, Oswald replaced Pulde in 1991.

“Bill had actually helped me and Tom Kattelman and Ross Thomas when we first started racing in Top Fuel,” explained Oswald. “Bill and his guys were racing with Kelly Brown, and he was the first one to help us when we moved into Top Fuel."

Over the next three seasons, Oswald and Schultz won three national events, runner-upped at four others, and finished in the Top 10 twice.

No win was more dramatic than their 1991 Gatornationals triumph. A broken wheelie bar cut the left-rear slick, tearing apart the left-rear quarterpanel. The team didn’t have a spare body, so they patched it back together, using parts of Tom Hoover’s Funny Car body, a lot of duct tape, and rivets.

“When I got out of the car at the top end, I didn’t think it could be fixed,” Oswald remembered, “but we got a lot of help from a lot of people like Ed McCulloch and Tom Hoover, and Bill just orchestrated the whole thing.

“Bill was a master at putting together race teams; I really enjoyed my time with him. He was just a fun guy to race with and was a godsend to me. He's just a pleasure to be around and a super-intelligent, amazing guy. I learned a lot from him. We enjoyed racing together, and I learned a tremendous amount.

“He was big on development and theory of how a car should be run. I can't tell you how many things that we’ve just started doing in the last few years that Bill was doing way back then.”

The team disbanded after the 1997 season, and Schultz picked up minor tuning roles for the next six or seven years, including European gigs for Englishman Alan Jackson and Swede Knut Soderquist, bringing to an end a brilliant career tuning race cars and winning events.

Schultz continued to live in California until just recently. He contracted COVID-19 at the end of 2020 and had a real rough go of it, according to his daughter, Jessica.

“He was hospitalized for almost two months, and he had to learn to walk again,” she said. “Twice we lost him, and those were tough times. But he learned how to do everything again; he was driving again and enjoying his life.”

An apparent auto-immune setback challenged him again, and he moved to Athens, Ga., to live with Jessica and her husband, Jim.

“I really think that he thought it would be a temporary situation as far as months or a year or something,” she said. “Then he could be back to California because he was a California kid, he loved it. He really did. There were probably 16 or 17 of his close friends who came to see him off when he left because there was a good chance that they may or may not see him for a long time or may not see him again, period.”

Although he had been given a clean cardio bill of health just days before the heart attack, we lost him Aug. 29, leaving behind a legacy of winning and a love of family.

“Racing just afforded us as a family, opportunities that were pretty amazing,” said his daughter. “Many times he would forego a negotiated rate of pay to bring my mom and myself over to England or Sweden when he raced there, having his employer pay for our travel expenses as well. This provided us with opportunities that meant so much. We would make it a habit to go to zoos and see things in different towns and have our favorite restaurants.

“He did a lot of winning, but never bought any extra trophies for himself for souvenirs. He’d say, ‘I'm not spending my money on getting that trophy. I know what I accomplished.’ That was his mindset. If the crew guys wanted one, he bought it for them, but he didn’t need one to validate what he did. I can't say it didn't mean something to him, because, of course, it's meaningful, but it wasn't necessary. For him, he was, at the end of the day, a gregarious really intelligent person, but he was a private person. And that's an interesting combination to be all those things.”

One thing Schultz certainly was is a winner, and a winner for a long time, which was the ultimate satisfaction to him.

"Winning Indy with Jack in 1968 certainly was a great feeling because it was our first indication that we could compete at the Professional level," said Schultz in 1994. "And winning lndy with Kelly is right up there, but overall, having had success for as long as we've had was really rewarding."

Russell Long’s career was short — just six years — but filled with highlights. "My career only lasted about an hour and a half, but it was a good one," he told me a few years ago when he spoke about his missionary work in Haiti to which he had devoted himself later in life.

His rise to respected driver was a Walter Mitty everyman dream, going from a kind polishing chrome to crewmember and then to one of the youngest drivers in Funny Car history.

According to a story in the June 1975 edition of Drag Racing USA, Long attended his first drag race in 1965 when he was 12 and “fell in love with Funny Cars like Lew Arrington's 'Brutus' and Dick Landy's injected Dart right away. From then on, I followed them when they were in the L.A. area, at Orange County, Irwindale, Lions, or wherever. I decided that I just had to get to work on one, and finally, in 1968, after hanging around for a long time, I got a job for $25 a week polishing Tom McEwen's Funny Car, which l did after school every day.'"

His hard work paid off when “the Mongoose” took him on tour beginning in 1969, and over the next two years, he learned what it takes to field a Funny Car. He left McEwen’s camp to work for the Ramchargers, hoping to further his goal of driving a Funny Car.

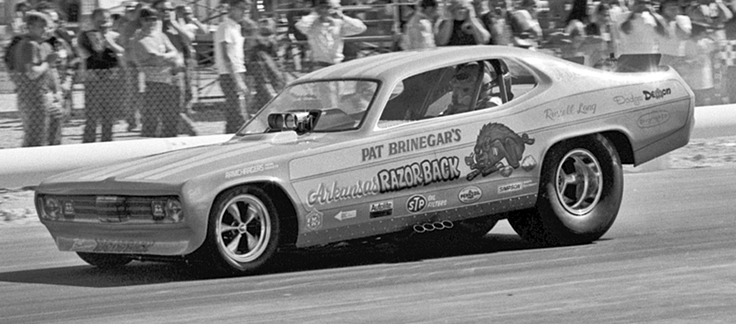

At the end of ‘71, McEwen sold his Hot Wheels Duster to Arkansas-based Pat Brinegar, and, being the great human and friend he was to so many people, told Brinegar to consider 19-year-old Long as his new driver.

"I never drove before in my life — I never drove a Q/SA or anything — but I had this really strong desire,” said Long.

Long hopped into the newly rechristened " Arkansas Razorback" and earned his license on five runs, capped by a best of 7.40 at 205 mph. At the time, he was the sport’s youngest licensed Funny Car driver but soon would lose that mantle to Billy Meyer.

But driving for Brinegar was nothing like working for McEwen, and after a short time, he returned to “the ‘Goose’s” nest, still looking for that next opportunity, which came after Charlie Proite and his driver, former Top Fuel shoe Gary Bailey, had a falling out.

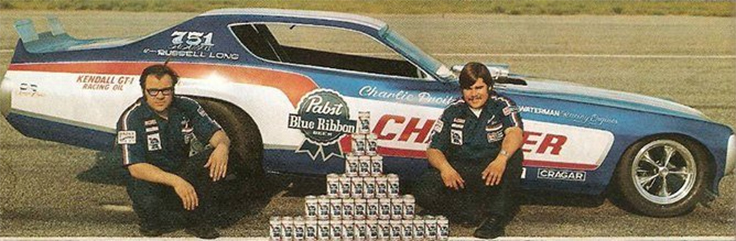

"While I was in Wisconsin with Tom, we heard that Charlie Proite was in need of a driver for his Telstar car and was staying at the same motel we were,” Long said. “I went to him and told him that I had my license and felt that I could be a good driver, but I couldn't prove it unless he put me in the car and gave me a shot at it. He gave me that chance, and it worked out. I drove for him all year, running a lot of 7.0s and 6.90s and gaining a lot of good driving experience. Then, at the end of that season, Charlie got a deal with Pabst Beer, and we brought out the Pabst Blue Ribbon Charger in the winter of ‘73."

Things took a wrong turn in August 1973 when Long lost control after blowing the crank, steering, and clutch out of the car and suffered a broken foot.

Long healed quickly, and good fortune smiled on him again when Bobby Rowe left Don Schumacher’s "Wonder Wagon" camp and Long dropped right into the saddle to finish out the year for Schumacher.

Over the next couple of years, he took driving slots in the famed Chi-Town Hustler, one of “Jungle Jim” Liberman’s match-race Monzas, and even licensed in the Pegasus Top Fuel car of John Durkee, who worked out of Sid Waterman’s shop, and drove McEwen’s second Navy/English Leather Duster.

In 1975, he took over the reins of Dennis Fowler’s Sundance entry from Tripp Shumake and drove one of the first Monza-bodied floppers, which graced that 1975 issue of DRUSA, the last issue of the fabled mag. Fowler owned a construction business in Alaska and vacationed in Arizona in the winter, where the car was kept. They raced together at least one more season.

Long told me a few years ago that he had plans for a jet-car future with an ex-Tommy Ivo jet and even was in consideration for a sponsorship from Skoal that ended up going to Don Prudhomme. He retired from racing and ran his backhoe business. Long's short-but-action-filled driving career ended long before he turned 30.

"I was the average kid who went to the races, fell in love with Funny Cars, and really wanted to drive one,” he said. “I didn't have any money to buy my own like some of the guys, so I started working from the ground up, polishing and working on them and driving the trucks, until it finally worked out that I got my chance to drive."

Hayden Proffitt, who began his drag racing career in 1952 at the famed Santa Ana Drags and went on to a successful career in doorslammers, early Funny Cars, and even jet dragsters, died Aug. 19. He was 94.

Proffitt was one of the most successful racers in national event and match-race competition in the 1960s and 1970s. Skilled as an engine builder and driver, Proffitt also built up a strong following of fans with his easygoing, gracious personality.

Proffitt's first drag car was a six-cylinder '53 Plymouth, which was followed by a '54 Buick and new Chevrolets in 1955 and 1956. He began running a '57 Corvette out of Bill Thomas' shop and was doing well enough to earn a parts deal from Chevrolet.

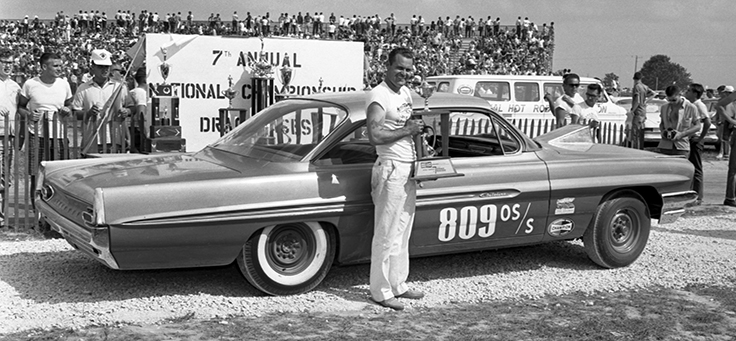

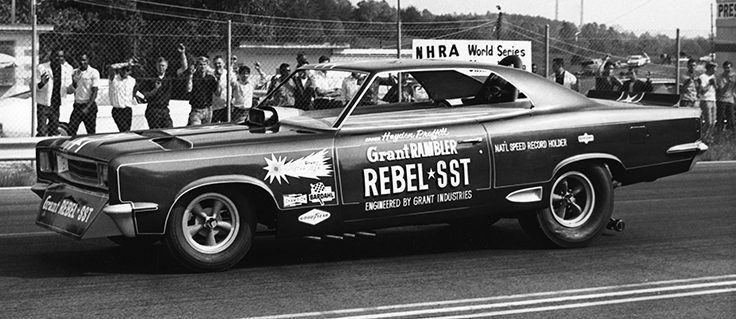

Proffitt drove his '62 Bel Air 409 to a Stock eliminator victory at the 1962 U.S. Nationals for his only NHRA national event title. When Chevy pulled the plug on factory support at year’s end, Proffitt was recruited to run Chryslers in 1963. In 1965, at the behest of Mercury officials, he built a pre-Funny Car Comet for the A/FX class and then built a Corvair Funny Car for 1966. In 1967, he joined the AMC team and fielded one of his most famous cars, the Grant Piston AMC Rambler Rebel SST Funny Car.

Proffitt ran the AMC Funny Car until 1970, then closed his engine-building shop. He built boat engines until 1976 when he purchased a rocket car that he toured with for four seasons. After posting a best time of 4.35, 349.77 mph, he bought Les Shockley's jet dragster, which he ran through 1982. Son Brad and grandson Hayden II followed in his footsteps driving jet-powered cars, and Brad even drove the USA-1 rocket to a speed of 351 mph in Edinburg, Texas. Hayden II drove an ex-Shockley ’57 Chevy jet truck at airshows with help from his father, Lee, and also recently licensed in Comp in Division 4.

I spoke to both his son Brad and grandson Hayden II over the last couple of weeks, and Brad told me that even at 94, he still followed NHRA Drag Racing, watching it every time it was on TV. They were both proud that Hayden carried on in the family business.

“The Hayden Proffitt name carries on,” said the proud uncle. “My dad had a full, colorful life, and he lives on in all of us.”

That’s a fine and fitting coda to this tribute to all three. Even though they’ve crossed the finish lines of their lives, they’ll live on with us in our memories, stories, and photos.

I’m admittedly late to the scene of these last two remembrances, as for some reason I never heard of the passing of female racing pioneer Judy Lilly (Aug. 9) nor 1960s Fuel Altered hero Gabby Bleeker (July 25).

Lilly began racing in Littleton, Colo., in 1961 with a D/Sports ’61 Corvette and won class honors at the 1965 Winternationals, which got the attention of Chrysler racing’s Bob Cahill and Dick Maxwell, who offered her a spot on the Mopar factory team with an SS/B Plymouth.

“Miss Mighty Mopar” switched to a Hemi Barracuda in 1968 and scored her first NHRA national event victory at the 1972 Winternationals, becoming just the third female national event winner behind Shahan and Judy Boertman (Stock at the 1971 Summernationals). She went on to record three more wins in Super Stock, her final victory coming in an SS/LA Plymouth Duster at the 1975 Fallnationals in Seattle, and three runner-ups, including at the 1975 U.S. Nationals. She was also named Car Craft Magazine Super Stock Driver of the Year in 1972, 1976, and 1977.

Lilly retired from driving at the end of the 1978 season and was idle for four years before returning to the cockpit in Pro Stock in Mike Musso’s entry, an ex-Dick Landy Omni. She finally qualified in her third and final event, at her homestate Mile-High Nationals in 1984, but she lost in round one. The car was just not competitive and up to her winning standard, so the team parted company, and Lilly went back into racing retirement.

Lilly was inducted into the International Drag Racing Hall of Fame in 1998 and the Colorado Motorsports Hall of Fame in 2005.

Who drives a car that even the fearless “Crazy Greek” Chris Karamesines said you’d have to be “nuts” to drive (and he did, one time)? That would be Gabby Bleeker. Modern-day fans probably don’t know him, but he was the king of Midwest Fuel Altereds in the early 1960s with a wild, blown Bantam that was all but unbeatable.

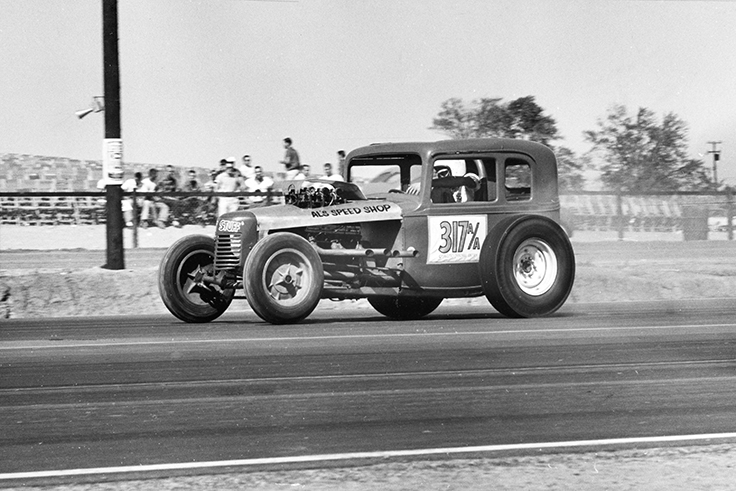

Bleeker raced just two cars in his 16-year career, a '36 Ford two-window that he ran for four years starting in 1952 and his most famous car, a '38 Bantam coupe. For the next dozen years, Bleeker worked to improve the Bantam, stretching the wheelbase, changing engines and carburetors, and, ultimately, blower. “In its final form, the car looked like a gutted 1930s gangster sedan with a motor that was too big,” observed the late Chris Martin, then NHRA National Dragster’s senior editor, in 1997.

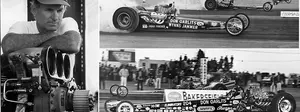

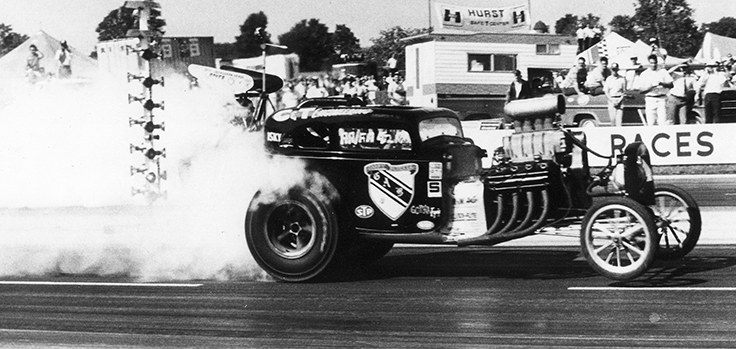

Bleeker got his first national recognition at the 1959 Nationals in Detroit (above) with an injected 462-cid Olds engine loaned to him by Karamesines, and he beat Walt Knoch’s feared Walt’s Puffer Too in the final of the AA/Fuel Altered field.

By 1961, he’d added a blower and became a match-race favorite throughout the Midwest. Bleeker's other big NHRA win came in the AA/FA class final at the 1968 Nationals in Indy, where he beat “Wild Willy” Borsch and his famed Winged Express in the final. (You can just see the top of Borsch’s famed wing above the smoke in the photo above.) Two weeks later, he retired after a hairy run at Rockford Dragway in Illinois after going through the traps sideways at 201 mph.

“I decided right about then that I wanted to quit,” he said. “I had had my fun."

Bleeker retired after 42 years as a cement finisher and lived in Evergreen Park, Ill., within a quarter block of Guzler fuel dragster owner Don Mattison and a half mile from Karamesines' shop.

"I was born and raised in or near this neighborhood," he said. "Myself, ‘Greek,' Mattison, and Bud Roche used to street race on Western Avenue, which is a stone's throw from my house. I look back on it now and think, 'What a life.' I started out here, and I finished up here.”

I heard from Mattison, who remembered fondly, “In my preteens and early teens, I spent many hours in our own garage because my dad and Bud Roche for years raced the Guzler dragsters, but I found myself riding my Stingray bicycle over to Gabby’s garage once in a while to hang out and sometimes in a rare occasion help him out. He had a two-car garage in the back of his small property, and I remember it had poor lighting. I don’t remember him having much machinery because I think 'the Greek' and CT Engineering did most of that. You have to remember this was the ‘60s and not many big shops with racing teams. Look at ‘the Greek’; for many years, even when Don Maynard was alive, they worked out of ‘Greek’s’ two-car garage. I also later in life worked on a few construction sites with Gabby because I was an electrician and he was a cement finisher.”

Bleeker may have worked in cement, but his legacy in the sport — and those of the others I’ve remembered today — were cemented a long time ago. Thanks for the memories.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator