Ed 'the Outlaw' Jones: Living life on two wheels for more than 45 years

In the pantheon of drag racing exhibition vehicles, no class has been officially accepted by the NHRA longer than the wheelstander, and no driver has more experience or longevity than Ed "the Outlaw” Jones, who first started scraping bumpers in 1976 and continues to this day, more than 45 years later.

Although jet dragsters had been around since the early 1960s, and ran as “outlaws” at other tracks, they weren’t officially accepted by NHRA until 1974, and wheelstanders like the Hemi Under Glass began running at NHRA events in the mid-1960s after the famed “Little Red Wagon’s” serendipitous transformation from race car to wheelstander in 1964.

In the match-race heydays of the 1960s and ’70s, it was important to stand out as unique, so that promoters like the legendary Bill Doner would book your act. While promoters could draw from a seemingly endless variety of sideshow acts — rocket-powered cars, hang glider-equipped motorcycle jumpers like Bob Correll’s Kite Cycle, guys towed behind motorcycles (Lee “Iron Man” Irons) or dragged behind cars (Jim “Bullet” Bailey), car-jumping go-karts (“Leaping Larry” McMenamy), and “Benny the Bomb” — cars were the main attraction and are why a lot of people came, and, of course, there were a lot of them, so standing out and being unique was important.

That was true with Funny Cars (like the wild Jeeps and other entries) as it was with wheelstanders, which have resembled everything from Army tanks to school buses and all manner of trucks and vans.

One wheelstander that proved unique was the Last Stage West of Tommy Maras, which was modeled after an Old West stagecoach. This is the car that became Jones’ first wheelstander and the car he continues to run today and for which he is certainly best known and loved.

SETTING THE STAGE

Jones, born and raised in Malad City, Idaho, didn’t set out to be an exhibition driver, but after years of running his ‘68 Camaro in brackets in Las Vegas and Salt Lake City yielded pennies after even big wins, he knew that if he wanted to stay in racing, there had to be a better plan for him and his young bride Wendy.

“I said, ‘You know what? I need to find another to make a living running a race car,’ so I parked the car for two years, and I was driving everybody crazy. Finally, a bunch of friends of mine, said, ‘Jonesy, you're driving us nuts. Please go buy a car. Do something. We don't care what: a Funny Car or a fuel altered or a wheelstander; just go buy something.’

"I went home and looked in the National Dragster and saw an ad from Tommy Maras about [booking] wheelstanders. I got on the phone and the next thing I know we were back East spending a weekend with Tommy, and we made a deal for me to buy it. I cashed in Wendy’s profit-sharing, cashed in my life insurance policy, borrowed some money from my dad, and we borrowed a pickup from Wendy's dad, and we went back there with everything we owned in our pocket, and we bought this old crazy car from Tommy.”

Maras had built the chassis himself in his Ashland, Ohio, garage, but the body was pure Hollywood. Tex Collins, who owned the aftermarket business Cal Automotive, which specialized in fiberglass bodies, was also a Western-movie stuntman. He got the idea of pulling a mold off on an old stagecoach and making fiberglass replica coach bodies for the studios, as it was much cheaper than building a stagecoach out of wood. Maras came out to California and brought the coach body for his new wheelstander.

Maras already had his next great wheelstander, the police-car-replica Smokey Plymouth Duster ready, so he sold the coach to Jones and took him to nearby Norwalk Raceway Park to teach him how to drive it, starting with a scary ridealong.

PUT ME IN, COACH

“Tommy says, ‘Just jump in and hang on the roll cage; here's a helmet.’ We take off down the track, and I’m holding onto the roll cage for dear life, and it was quite a ride. Then he says, ‘Jump in it and run it.' He didn't tell me much about steering it or anything other than there’s two [braking] levers down there and that will help you.”

[For the uninitiated, with the front end in the air, wheelstanders are “driven” by applying either the left or right rear brake to steer the car. The driver looks out through the floorboard of the wheelstander to see.]

“So, I take off, and I'm doing pretty good, but it's going towards the wall. I pull the brake, but your instinct tells you to turn the steering wheel, so I had the steering wheel turned when it came down, I spun it around it went into the guardrail backwards. It didn't hurt it too bad and off I went.”

Jones spent the next year learning how to drive the coach on two wheels, driving on an out-of-use two-land road in Malad City while simultaneously refining the coach.

“The basic frame was 2 by 3 by .120 wall tubing, and it was built very, very strong, but the cage was made from water pipe. We built a really good roll cage in it — we went overkill on everything because I don't need to worry about weight — and modified everything from the front axle and strengthened the chassis and rear end. We built a NASCAR-style motor with steel rods and more for endurance than horsepower. The one thing that’s still original 46 years later is the body."

So, exactly how does Jones drive a wheelstander?

“My left hand holds the steering [largely for bracing in mid-air] and then my right hand is very busy. I have two levers down on the floor, so I really keep busy with those. You just have to do it by reflex; you can't think, ‘Oh, I'm going to the guardrail, I need to pull a lever to keep me off the guardrail.’ I'll make a run, and I can't even tell you what levers I used. I've learned that I don't have time to even think about it

“I look down through the floor, where I have a fiberglass windshield looking out right over the axle. We used to drive looking out the window at the guardrail or just looking at the ground, but NHRA made it mandatory that we could see where we’re going. The car is up at about 37 degrees, so I can see downtrack to see where I’m going.”

SWEET DEALS

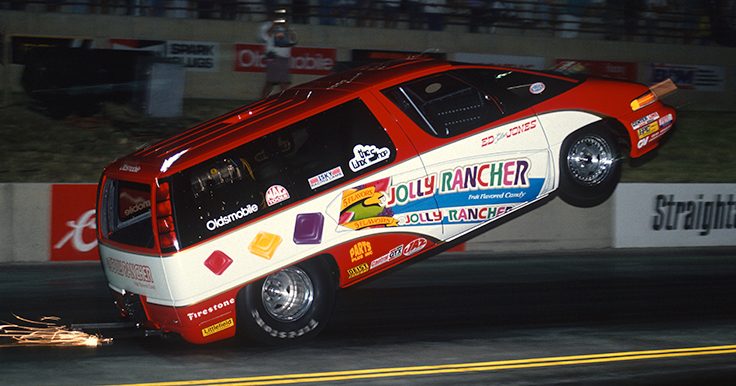

In addition to his two-wheeled prowess, the Joneses are fan favorites for another reason. Since 1982 — for 12 years under the sponsorship of Jolly Rancher and for the last 22 with Jelly Belly — they’d tossed candy samples to the crowd after every run.

Colorado-based Jolly Rancher already sponsored home-state Top Fuel drivers like Johnny Abbott and the Kaiser brothers and an up-and-coming Funny Car driver named John Force when company Owner Bob Harmsen and team chanced upon Jones at a 1982 match race at Orange County Int’l Raceway.

“Harmsen already had a stagecoach that they drove around on the street that they used for parades and things, and Jerry Kaiser introduced me to Bob Harmsen, and we were together for 12 years until the company was sold.”

It was during this time that Jones spent two years creating and perfecting a flame show to complement the wheelstands, using a separate fuel canister spraying gasoline into the headers, and it was Harmsen who came up with the idea of adding cinnamon oil to the fuel so that that the exhaust would smell like the classic Jolly Rancher Fire Stix candy.

Early on in the Jolly Rancher program — and perhaps pulling a page from the playbook of the old Baby Ruth-sponsored Funny Cars of the 1970s that used to heave miniature candy bars into the stands after a run — the Joneses started doling out handfuls of candy to the fans.

“Rather than just come back up the track and just wave, I came up with the idea of throwing the Jolly Ranchers up into the fans, and it was just really good,” he remembers. “We went through tons of candy. We used to get pallets of candy delivered, and, of course, we continued that tradition with Jelly Belly.”

After the Jolly Rancher deal ended, the Joneses were not actively shopping for a new sponsor and also had bought Drag City Raceway in Pocatello, Idaho, but another chance meeting, in 2000 at Northern California’s Sacramento Raceway with the Rowland family, who ran only locally based Jelly Belly candy (made famous by former President Ronald Reagan) and sponsored a local racer, changed all of that. Herm Rowland Sr. had been friends with Harmsen and reportedly greatly admired the forward-thinking Harmsen’s racing program and struck a deal with the Joneses that continues to this day.

The Joneses have spread their sponsors’ messages (and products) far and wide, with trips to Japan and Germany and were featured in a Guinness Book of World Records television show (for a record 2,298-foot wheelie at Sears Point) that was viewed in 44 countries.

“I like to think that anyone who’s ever come to a major drag race has either seen the car, smelled the car, heard the car, or had a piece of Jelly Belly,” Jones says proudly.

IMPERFECT LANDINGS

We all know that what goes up must come down, and that goes for wheelstanders, too. Usually, the return to terra firma is no big deal, and Jones has only had a few non-standard landings among his hundreds and hundreds of passes.

One came at the 1985 NHRA Fallnationals in Phoenix, where a kingpin broke upon landing and sent him into the guardwall. Damage was minimal, and he was back in action the following weekend.

Less fun was a dark and scary ride at Bonneville Speedway in Salt Lake City.

“That used to be kind of a wild track where people would come out and party and have keggers; you never knew what people were going to do,” he recalls. “One night we were running and [a fan] thought it'd be really neat to see us run in the dark, so he crawls up a telephone pole and turns the lights off.

“I'm going down there and the lights go off, and it's like driving inside of a hat. I couldn't see anything. I set the car down, and I tried to figure out where I was. I have the car shut off, but I was still going, and I finally went into [top-end] gravel and spun around and tipped it on a side. It didn’t hurt that car bad, and we got it all fixed up.”

TWO WHEELS, ONE HEART

Wendy, like Ed, hails from Malad City, and the two Malad High School sweethearts have been married now for 52 years.

“Wendy's been there helping me the whole time,” said Ed. “We've been together since day one. Without her and her family, and my family, I wouldn't be here today. We make a great team. I wouldn't have been able to do without her. She still supports me, and we love traveling together. She sells T-shirts and does a bunch of things and takes care of a lot while I do the driving stuff."

Although she hasn’t been on two wheels, her husband brags that she’s also a pretty good driver. When they were track owners and attended NHRA’s annual Track Operators Meeting, Wendy twice won the friendly bracket race and also won closest to the dial and best reaction time.

DIVERSIFYING

I guess Wendy could have driven because at one time they had three wheelstanders in the stable. The Joneses added a vintage fire truck wheelstander in 1997 to run in the west while the stagecoach stayed out west and experimented with an Oldsmobile Silhouette van that took nine months to build but only ran for a short time in 1992 before being sold to a racer in Australia.

The van was fast — 9.82 at 132 mph — whereas the stagecoach typically runs in the 11s at 110 mph. The firetruck suffered from some aerodynamical setbacks caused by the large front fenders catching air, but remains a solid performer and fan favorite.

Power, as always, comes from a supercharged-on-alcohol 427 Chevy built by Vern Smith and his sons at the Horsepower Farms in Benson, Utah, since the time the boys were in diapers and working on Briggs & Stratton engines.

The engine has a strong oiling, fuel, and cooling system and could help Jones sustain a wheelie for at least a mile if he could find the room to do so.

EXIT, STAGE LEFT? NOT YET

Jones thinks he could go a mile on two wheels (I had to really push him for an answer) but was less cagey about how many more wheelies he has in his future.

“When I got my [wheelstander] license, I was No. 52, and there were 29 drivers out there doing it. Today, I think I can count the number on two hands. We haven't had the new blood coming in — a lot of people have come in and tried and haven't lasted very long because it’s not an easy business.

“There are three things that will keep me going: As long as I still have a sponsor, as long as our health is good, and as long as the fun’s still there. Our relationship with Jelly Belly is still going strong; they’re like family, and we love being ambassadors for the company. Healthwise, I’m 73 but have great health, so no problem there either. And fun? Everywhere we go, we have so many friends it's just like a family reunion, and there’s this terrific camaraderie.

“We couldn't have done this without the sponsorships and without the family support of people like the New family at Firebird Raceway or, of course, without NHRA, who have kept wheelstanders in the rulebook long after they could have dropped them, and I appreciate that very much.

“It’s been a tremendous ride and a tremendous life.”

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator