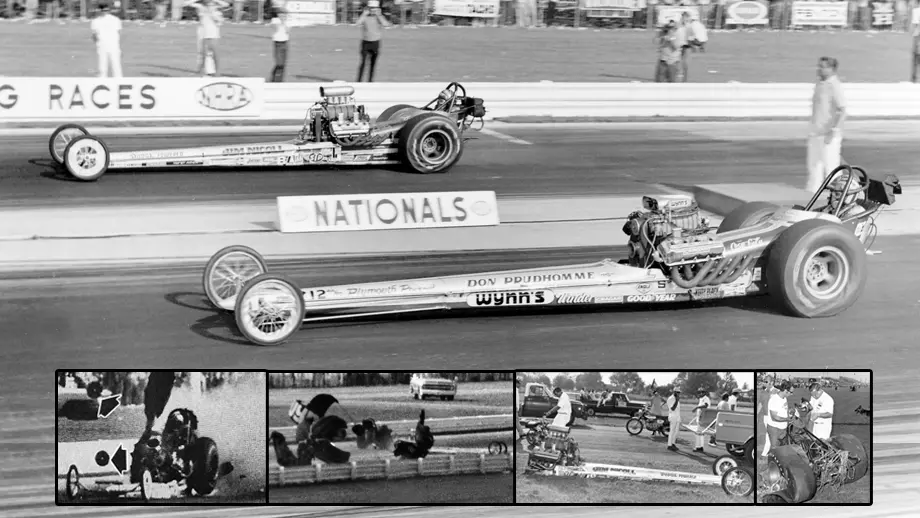

Reliving the U.S. Nationals Top Fuel final that no one will ever forget

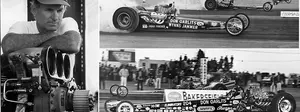

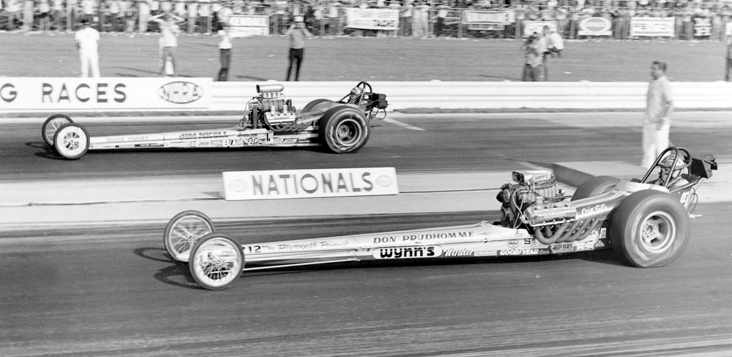

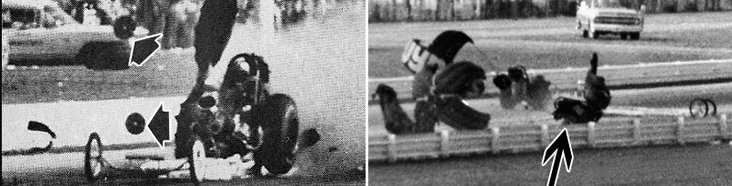

Even 50 years later, it remains among the most dramatic and poignant footage ever recorded at an NHRA national event. The 1970 U.S. Nationals Top Fuel final, Don Prudhomme vs. Jim Nicoll. Nicoll’s clutch explodes at the finish line, cutting his front-engine dragster in two at his feet. The driverless front half of the dragster eerily sliding down the track ahead of Prudhomme’s slowing dragster in the shutdown, “the Snake” sure that his longtime friend had been killed. Prudhomme’s emotional interview, suggesting he was ready to quit. All of this played out on national television, on ABC’s popular Wide World of Sports program gave the nation a window into our sport that probably resonated deeply. Very powerful stuff.

You’ve probably seen it countless times in many ways, but the best for me is below, which shows the accident and the frenzied activity of the aftermath. Tow vehicles and ambulances racing downtrack, medical personnel huddled around Nicoll’s cockpit, Prudhomme’s reaction.

"I think I'm quitting," Prudhomme says, near to tears. "Oh my God. I seen that car go by me. I couldn't believe it. There was no back ... there's no back section on it or nothing ... How is he? How bad is he? How bad is he?"

Nicoll, of course, survived the scary incident and I had the great pleasure of talking to both drivers about their infamous moment together on numerous occasions before Nicoll’s passing on Christmas 2014 at age 76, and I’ve compiled the best of my notes below to provide some context to history.

By the 1970 U.S. Nationals, everyone knew who Don Prudhomme was for all of his previous successes — starting with his dual 1965 wins in Pomona and Indy in Roland Leong’s Hawaiian, but fewer knew much about Nicoll, which is a shame because – Indy accident notwithstanding — he probably had a better season than Prudhomme and, in fact, was named Drag News Top Fuel Driver of the Year at season’s end.

Nicoll had already reached two NHRA finals that year, at the Springnationals in Dallas where he broke the rear end against Bob Gibson, and at the Summernationals in York, Pa., where he broke the camshaft against Pete Robinson.

At Indy, Prudhomme methodically worked his way to the final with victories over mentor "TV Tommy" Ivo, Danny Ongais, and Robinson, then reached the final on surprise low qualifier Brian Budd’s red-light. Prudhomme’s best run of eliminations had been a 6.43 against Ongais but also ran 6.45 to beat Robinson.

Nicoll’s best pass was 6.57 in beating Jim Walther in round one, which he had followed with victories against Gerry Glenn and Marshall Love and, like “the Snake” reached the final on a foul start, albeit from a much more experienced driver than Budd. Some guy named Don Garlits.

Although both were slingshots, Prudhomme’s bright yellow Wynn’s Winder was powered by the relatively new 426 Hemi. Nicoll’s car ran the older 392-style Hemi. The even bigger difference was in the clutch. While Prudhomme was running a traditional Schiefer pedal clutch, Nicoll was running the then-experimental Crowerglide, one of the few to do so in Top Fuel at the time. Although its centrifugal “slipper” design would before the standard for decades after, it was still new technology.

The two finalists launched together, and it was obvious that Nicoll had found the tune-up as they stayed locked together the length of the quarter-mile. Prudhomme’s yellow rail tripped the win light for a narrow 6.45, 230.76 to 6.48, 225.56 victory.

Then all hell broke loose.

Although not enough pieces of the clutch could be found for a thorough forensic evaluation, Nicoll blamed bad heat treating on the clutch stands that allowed the six bolts that held the pressure plate on to come loose. All he remembers was the clutch starting to slip as the two neared the lights. The exiting discs cut the car in two at his feet, and the back half containing Nicoll went over the guardrail and tumbled in the grass.

“I remember everything but the actual crash,” recalled Nicoll. “I remember doing the burnout, and it seemed like the clutch wasn’t acting right. When I left the starting line, everything was cool, and we were side by side, and about 1,000 foot, I felt the clutch start to slip. The last thing I remember was reaching over and putting my hand on the parachute handle just in case, but that probably saved my bacon.

“I remember waking up in the ambulance and then went out again and woke up in the hospital. I had a concussion, and my right foot was swelled up. They’d cut my firesuit off me, so I just left in one of those damn gowns with my ass hanging out. I went to the hotel and then to the banquet that night. When I saw the footage, I was surprised how bad it had been; I had no clue.”

Within a week, Nicoll had Lester Guillory build him a new car in Houston and was back in action the next weekend, when, coincidentally, he lost again to Prudhomme.

“Prudhomme said he was gonna quit after that deal in Indy, but he beat me the next weekend!” Nicoll told me a few years ago.

The duo was reunited at the 60th U.S. Nationals in 2014, where they cut up on one another and Prudhomme explained his emotions.

“In those days, if you saw someone crash and go over the guardrail, it was over; they’re dead,” he said plainly. “We had lost a lot of guys in those cars; they were extremely dangerous. That’s one of the reasons I was so upset.”

In a separate interview I read recently, Prudhomme said that he even thought he saw, through the smoke and sparks, parts of Nicoll or his firesuit on the mangled end of the front half, so you can understand his emotion.

Even though the front-engined dragsters claimed so many lives and he never won an NHRA national event in one again, Prudhomme was still a fan of the slingshot

“The front-engined dragster, without a doubt, was the most thrilling, most fun thing you could ever possibly have,” he said. “The engine was right in front of you; you could see everything — the exhaust pipes, the blower. There were no starter motors or any of that jazz. The way you started them was push-starting. A car or truck would be behind you, you’d get going, let the clutch out, feed a little fuel, shut it off, and hit the starter switch, and it would go bahhhh-bup-bup-bup and pull away and then start idling. It was a real turn-me-on-er. The girls fell out of the stands. It was pretty cool; I gotta tell you.”

Also at that 2014 reunion, the re-created 1970 Nicoll Top Fueler was on display, along with the original roll cage, which had been found recently in the Dallas area and had been being used as — gasp — a child’s swing. Someone had found it behind the T-Bar chassis shop in Dallas, where Nicoll had dropped off the remains, and repurposed it. At Indy, fans were invited to sit in the cockpit with a note that read simply: “Have a seat and take a ride. We have kept his cage intact for your enjoyment.”

Did I? What do you think?

Phil Burgess can reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE