Remembering Art Chrisman and Chuck Etchells

Chuck Etchells

The last week provided a double shock of loss, with the passing of Funny Car barrier breaker Chuck Etchells Wednesday, July 6, and the loss of drag racing icon Art Chrisman the following Tuesday. The loss of Etchells was unexpected, a sudden death at age 61, and although many of those close to Chrisman knew that his passing was imminent – he had battled cancer for quite some time – it was no less shocking that he was gone at age 86 when the news arrived.

Etchells engraved his name in the NHRA history books on that magical weekend in Topeka in 1993 when both the four-second and 300-mph Funny Car barriers were felled – the former by Etchells, the latter by Jim Epler – and although Chrisman's headlines were written in a time before mass media and televised drag racing, it’s impossible to overstate his place in the sport’s history, so I’ll talk about him first, borrowing generously from an article I wrote about him 15 years ago when he was voted No. 29 on the list of Top 50 Drivers of NHRA’s first 50 years, ahead of guys like Chris Karamesines, Dick LaHaie, and many others.

The criteria for that list was based not solely on behind-the-wheel accomplishments but on historical, mechanical, and promotional legacy, which is why Chrisman was the perfect fit. It’s hard for fans of today to truly understand how different things were in that time. I think we’re all aware that back then racers did it almost all themselves, but I think even I still have a hard time understanding what that means and reconciling it to today’s army of specialists.

Hot rodding's earliest heroes didn't get a new race car every year, nor did they rely on professional chassis builders to create their racing machinery or fabrications specialists to create the bodywork. These heroes never depended on air-gun artists to paint their machines or stood back and watched hired wrenches build and tune their engines before hopping into their chariots. More often than not, these ancestors of acceleration did it all themselves, wiping their dirty hands clean before climbing into the cockpit to try out their handiwork, and few better exemplified this standard than Chrisman.

Chrisman's family moved from Arkansas to Compton, Calif., during World War II and owned an automobile-repair shop, Chrisman & Sons Garage, where Chrisman quickly learned about cars and developed an interest in racing.

“I built my first hot rod, a ’32 Ford, right after World War II when I was 16,” Chrisman told NHRA National Dragster in an interview several years ago. “I then built a custom ’36 Ford sedan, which was the first car I raced at Santa Ana and El Mirage.”

Chrisman and his brother, Lloyd, began racing the Ford four-door sedan on the Southern California dry-lake beds. That was followed by a '34 Ford that hit a stout 140-mph clip and a tube-frame, chopped and channeled '30 Ford coupe. Chrisman became one of five charter members of the Bonneville 200-mph Club after driving Chet Herbert's Beast streamliner past the double-century mark (and eventually up to 235 mph) in 1952. The next year, the Chrismans' homebuilt coupe reached near-200-mph speeds.

Racing was clearly in the family's blood. Chrisman's uncle, the late Jack Chrisman, won Top Eliminator titles at the first Winternationals and at the 1962 U.S. Nationals. In 1964, Jack was the first driver to wheel a blown and injected nitro-burning Funny Car. Jack's son, Steve, was a competitive alcohol and nitro Funny Car racer in the 1980s.

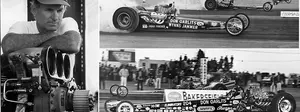

Art Chrisman, in his famed #25 dragster, was the first drag racer to exceed 140 and 180 mph and the first winner at the Bakersfield U.S. Fuel & Gas Championships in 1959. Chrisman was partners with Leroy Neumeyer on the #25 car. When Neumeyer was drafted to fight in the Korean War, Chrisman began to race the machine, which would become one of the most celebrated cars in drag racing history.

"It was probably built in the early 1930s by some backyard mechanic," Chrisman reflected in 1991, "but I have no idea who that was. This was not a factory car, just some machine a guy put together. I had seen it around town, and because it was so unusual, it caught my eye. [Neumeyer] traded his motorcycle for the car. We ran it at the dry lakes in the early '50s, and in 1953, we took it to the drag races, the first time at Santa Ana. We just wanted to see if it would go straight.

"Some months earlier, I had stretched it from its original 90-inch wheelbase to 110 inches, set the driver back farther in the car, and threw a coat of black primer on it. We ended up taking it apart that day and didn't run it. But the next time out, same track, same year, we had the copper paint job on it, the big #25 on the driver's side of the body, and a Chrysler under the hood. That's when we went 140."

The familiar #25 cemented its place in the history books as the first car to make a pass at NHRA's first national event, the 1955 Nationals in Great Bend, Kan. Chrisman took part in the ribbon-cutting ceremony, then made the opening lap of the race.

“It was [NHRA founder] Wally Parks’ idea for us to make the first run,” said Chrisman. “When I made that pass, I had no idea of what we were starting with NHRA’s first national event, but I did see the handwriting on the wall when I got to look at the slingshot dragsters of [eventual event winner] Calvin Rice and Mickey Thompson. We had plenty of power with our Chrysler engine, but we couldn’t take advantage of it because our car would just smoke the tires.”

In 1958, as #25 was beginning to show its age and a new breed of dragster, the slingshot, was beginning to make its mark, the Chrismans, along with Frank Cannon, built their famed Hustler I dragster. Chrisman recalled that he first attempted to modify #25 into a slingshot design, “but it would’ve looked so weird that we just decided to build a new car from the ground up,” he said.

Built at the Chrisman garage, the new entry won the Best Engineered Car award at the 1958 Nationals in Oklahoma City and was featured on the January 1959 cover of Hot Rod magazine.

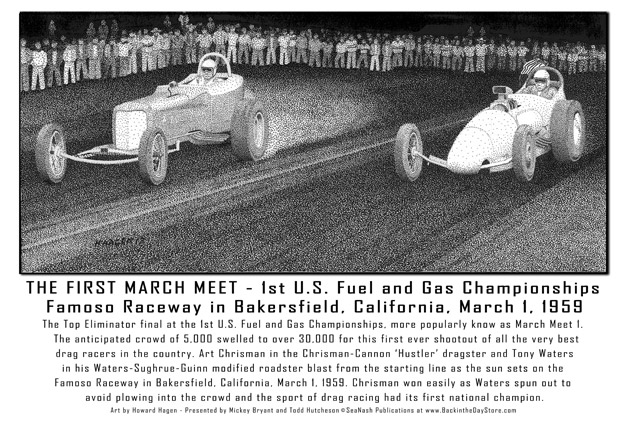

The car, powered by a blown 392-cid Chrysler engine stroked out to 454 inches, became the first drag racer to crack the 180-mph mark with a 181.81-mph run on the back straight of Southern California’s Riverside Raceway in February 1959, just a month before the historic first March Meet, known then as the U.S. Fuel & Gas Championships.

"We ran a 180 that day and two 179s, so we knew we had a runner," he said. "That run gave us a lot of confidence going into the first Bakersfield race, which was run in March. We knew that all the big guys from California would be there, as well as Don Garlits and some of the Eastern racers. We wanted to show them we were for real with that 180."

Chrisman won that historic first Smokers Meet, running as quick as 8.70 at 179.70 mph and trailering some of the best fuelers in the sport. He capped the event with a victory over Tony Waters in the Waters & Shugrue roadster in a near-pitch-black final.

Drag racing biographers Mickey Bryant and Todd Hutcheson sent me this wonderful Howard Hagen print that shows that famous 1959 March Meet final round.

Chrisman ran that car through the end of the 1962 season, scoring Top Fuel runner-ups at the 1960 and 1961 Bakersfield races, then went to work through 1972 for Ford Motor Co.'s Autolite Spark Plug Division, which put an end to his driving career but not his association with motorsports.

The restored #25 made the opening pass at the 25th annual U.S. Nationals in 1979.

“I not only got to work with Connie Kalitta, Don Prudhomme, and my uncle Jack when they received their new Ford SOHC 427s, but I also spent every February in Daytona [Fla.] and every May in Indianapolis,” he recalled. “I also worked with racers such as Mario Andretti, Dan Gurney, and A.J. Foyt. Some of our projects at the Indy 500 included working with the Ford pushrod small-block engine that was based on the 289-cid engine and the dual overhead cam engine, which won a lot of races there.”

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of the U.S. Nationals, Chrisman worked with his son Mike and Steve Davis to restore #25 and duplicate his first pass at the inaugural event to begin the 1979 race. The ritual was repeated again at the 50th U.S. Nationals in 2004.

Former NHRA Vice President and Competition Director Steve Gibbs was incredibly close to Chrisman, especially in his final years.

“We all have our drag racing heroes,” said Gibbs, who also shared some of his thoughts in the video at right, during Chrisman’s installation into the SEMA Hall of Fame. “Some from their racing accomplishments and mechanical skills, others from their personal conduct, or character. When one person has all those traits and is later to become a close personal friend is a reward that few experience. Art became like the older brother I never had. He was a racer’s racer and a man’s man. He was married to his wife, Dorothy, for 62 years, which should also tell you a lot about him.

Chrisman, left, Steve Gibbs, right, and Ron Capps at the NHRA museum in 2014, in front of the exhibit that honors the start of our sport and #25.

“The strength he showed during his dying days was unbelievable. Never once did I hear him complain or feel sorry for himself. ‘I’m fine’ was his response to questions about his situation, when we all knew it wasn’t. I can only hope I have a tenth of his strength and dignity when my time comes. The reality is that I'm at an age when many of my friends are dying. It's a cruel reality, and each loss hurts. Losing Art Chrisman is different; it's life-changing. What started out as a young kid idolizing a big-name racer turned into a very close personal friendship. When we left Art's house on Monday night, I knew it was the last time I would be with him, and it left a huge hole in my heart. But it was his time to go, and there was honestly a sense of relief in knowing he would soon be free from a long and courageous fight.

"It's a shame that some of the younger folks do not have full knowledge of what Art contributed to the world of drag racing and hot rodding. Many of us do know, and he was simply the best. I'm thankful for his friendship and take comfort in knowing that he felt the same. Vaya con Dios mi amigo.”

Legendary race car builder Tom Hanna echoed Gibbs’ sentiment, calling Chrisman “the last of a breed of most extraordinary men. If there be a hereafter, Art Chrisman’s place was well earned.”

Fans like Insider regular William McLauchlan also expressed their appreciation of Chrisman

Fans like Insider regular William McLauchlan also expressed their appreciation of Chrisman

“Art Chrisman was before my time,” he wrote. “His racing career ended before I ever opened a Hot Rod magazine or attended a drag race. When I did start reading National Dragster’s event coverage I always wondered why they had a photo of the Autolite spark plug guy – who was this guy? He wasn’t racing. Well, I would find out. In old Hot Rod magazines I saw his cars were fast and first class in preparation. In the Rodder’s Journal the cars he built were incredible. Having breakfast with Steve Gibbs one morning he told me Art was his hero. And then I went to Bakersfield and thought the Hustler was the loudest car there (sorry Mike Kuhl and others). Walking through the pits I saw Art standing by himself next to his car. I decided to take a chance and go talk to him. I told him his car was loud, which he said it always was even when they raced, and told him I liked the street rods he built. He told I should come by some Wednesday night but to be sure to bring food. I was really taken back by his openness and character. This guy was the real deal. If someone wanted to know how to be in life, be like Art.”

A memorial and celebration of life for Chrisman will take place Saturday, Aug. 27, from 1 to 3 p.m. at the Wally Parks NHRA Motorsports Museum presented by the Automobile Club of Southern California.

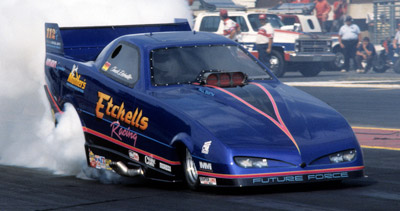

In a fine career that included 13 NHRA national event wins – from his first, a wild finish in Englishtown that ended with opponent Johnny West unconscious after a guardwall slam, to the last, a triumph at the 1998 World Finals – Etchells left his mark on the Funny Car class as a fierce competitor, superb marketer, and constant foil for John Force.

Four of Etchells’ wins came after vanquishing Force at the height of his mid-1990s power in final rounds, but nine of Etchells’ 13 runner-ups came at the hands of the sport’s most feared flopper pilot. Force respected Etchells as he respected and fought everyone who strove to take away his hard-earned crown, including Al Hofmann, Whit Bazemore, and more. In the 55 races that spanned the 1993-95 seasons, one or both of them were in 33 of those finals, and Etchells finished in the top five seven straight seasons, from 1992 through 1998, with a career-high finish of No. 2 behind Force in 1993.

And although Force beat Etchells way more often than Etchells ever beat Force, few – especially Force –will ever forget the biggest and grandest time that Etchells beat him, in the race to break into the four-second zone.

Funny Cars had begun knocking on the four-second door the previous season, when Cruz Pedregon steamed to a 5.07 in the McDonald’s Pontiac at the NHRA Keystone Nationals. The following spring, Force hammered out a 5.04 in Houston, followed by a 5.01 in Englishtown. There seemed to be little doubt in anyone’s mind – especially, apparently, Force’s – that he would be the one to do the barrier breaking.

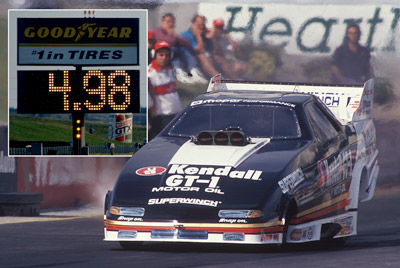

Etchells had other ideas. Force had already locked up the season championship, so Etchells and crew chief Tim Richards set their sights on the first four. The stage was set for history at Heartland Park Topeka in early October.

“We had run a 5.06, 292.20 at Maple Grove and felt that coming into this race we could do it,” Etchells told National Dragster. “I ran a 5.04 blowing a blower at 1,200 feet [in Englishtown] in July, so we've had the power for some time. What we needed were the conditions. As soon as we arrived here, I got the feeling that we had a shot at it. As soon as we got out of the truck, we could tell that the air was good, and our first run told us that the track was smooth and in excellent shape. Inside, I felt that if Force didn't step up dramatically, we could get it."

Not long after Castrol's John Howell, second from right, and John Force announced a $25,000 bounty for the first four-second Funny Car run, Etchells, second from left, swooped in and stole Force's prize.

No one did well in the first qualifying session in Topeka, but with the cool evening session approaching, a special announcement was made on the starting line. Castrol GTX Motorsports Manager John Howell announced that his company would present $25,000 to the four-second barrier breaker. Force – sponsored then, of course, by Castrol – apparently got caught up in the excitement of the moment and announced to the crowd that he'd pay half of that $25,000, probably figuring he would be writing a check to himself.

Force's Olds was in the second pair (this was before qualifying was run as it is today, with the quickest drivers from the first session running last in the second session) and Etchells in the sixth. Force had run 5.08 to top the first session, so it was a better than good bet he was going to crash through the barrier. Then came an unexpected break for Etchells … or should I say “brake”? During the burnout, Force’s Castrol Olds broke the left front-brake caliper, and crew chief Austin Coil had to shut him off. "The caliper was locking up the wheel," said Coil. "John could feel the shudder when he used the brakes after the burnout. When he released the brakes, the car wouldn't roll."

Four pairs later, Etchells, who had run 5.16 in the first session, promptly put a 4.987 at 294.31 mph on the scoreboard.

"Well," Force said, "I picked a great time to shoot my big mouth off. Etchells and his crew are good guys, and they did it fair and square. Our team has had a lot of things go our way this year, so I guess it was someone else's turn to have their moment."

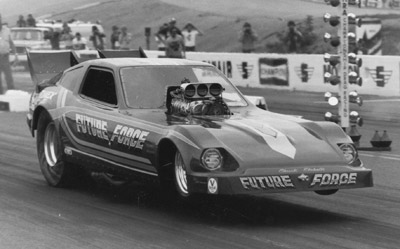

Etchells' moment was long in coming. He had begun attending drag races at Connecticut Dragway in 1970 at age 16 and soon began racing his own ’67 Dodge R/T, eventually getting it to run in the high 10s. Then he made the huge leap in 1978 by purchasing a Chevy Monza Funny Car from Bruce Larson. With brother Gary and pals Pete Hyslop and Bill Hatzell, he went nitro racing. He called the car Future Force, which he certainly hoped to be, though there were certainly few guarantees at the time.

“We knew nothing about nitro engines,” he admitted, “but Bruce spent hours on the phone with us, trying to get us dialed in. I don’t know how he managed to put up with all that, but he did.”

Etchells earned his license with a respectable 6.60 at 220 mph and a few years later traded the Monza shell for a Datsun body before upgrading to his first car, a Murf McKinney-built Pontiac Trans Am, in 1984.

“We were still blowing up a lot of stuff back then,” said Etchells, "and upon the suggestion of [Englishtown’s] Vinnie Napp, I called Paul Smith and his son Mike for some help, which turned out to be a good idea.”

In 1990, Etchells finally won his first NHRA national event at the Summernationals and also won the IHRA Funny Car championship. A year later, Etchells was forced to park the car until his agent, Bill Griffith, came up with sponsorship help from Nobody Beats The Wiz home entertainment centers, which allowed Etchells to hire crew chief Maynard Yingst, who helped tune Etchells to three victories and a fifth-place finish in the 1992 standings. Tragically, Yingst suffered a fatal brain aneurysm on the final day of qualifying at the Houston event in 1993.

While attending services for Yingst in Linglestown, Pa., Etchells ran into Tim and Kim Richards, who were between jobs. “We were snowed in at the local Holiday Inn,” said Etchells, “and we got together in one of the rooms and managed to put together a deal for the rest of the year.”

Etchells went on to record two wins and a career-best second-place finish that year, capping it of course with the four-second run. Etchells finished in the top five five more times through 1998 but decided at the end of that year to replace himself as the driver with Bazemore, who brought extra money to the team with backing from Turtle Wax for the next two seasons. In 2001, Etchells formed a two-car team, driving one of the cars himself and hiring Jim Epler to drive the other. Lack of sponsorship backing forced Etchells to retire for good near the end of the season.

Art Chrisman and Chuck Etchells. Two guys on almost opposite ends of the drag racing history timeline but joined by their love of competition and their place in all our hearts.