No more wonderin' about the Wonder Wagon story

|

There’s nothing I love better than getting to the bottom of a good mystery, and when it comes to drag racing history, no chapter may be more misunderstood than Wonder Bread’s involvement with the sport back in 1972-73. Most longtime drag racing fans are familiar with Don Schumacher’s ultra-swoopy Wonder Wagon Vega coupe that he debuted at the 1973 U.S. Nationals, and some may even remember that the sponsorship program actually began with a completely different team, with Vega panel wagons at the end of the 1972 season, but the real mystery meat of this story sandwich has never been told, as far as I know. I’ve told the story as I “knew” it several times, and that version was as stale as two-week-old bread, and each time I wondered if I had the true story.

Well, wonder no more.

I’m not one to loaf around, and I relished the chance to slice through half-baked rumors to really sink my teeth into the project and cut away the crust of confusion. I mustard mustered all of the resources and began methodically tracking down all of the players, which included original dealmakers Bob Kachler and Don Rackemann, original drivers Glenn Way and Kelly Brown, and, of course, Mr. Schumacher. The interesting thing was that all of them also were eager to share their involvement to set the story straight and provide what I hope will be the definitive telling of the story.

What’s really important to remember in this little chapter is that ITT Continental Baking (maker of Wonder Bread) was probably the first Fortune 500-type company from truly outside of drag racing to get deeply involved in the sport. Of course, Mattel/Hot Wheels is considered the groundbreaker in that department, but there was a natural car tie-in component to that deal, where there wasn’t to the Wonder deal.

Where there’s a Way …

Glenn Way, left, with Kelly Brown and the original Wonder Wagon.

|

Although everyone else seems to get a hunk of the credit, it’s actually Glenn Way, a fuel altered driver from Arcadia, Calif., who was the genesis for the deal. He approached Kachler, a respected dealmaker and owner of a multifaceted business, Racing Graphis, in Long Beach, Calif., to help him get a sponsorship for a new fuel altered team, but with the growing popularity of Funny Cars, they went that direction instead.

Kachler, who shared office space and a creative environment with super artist Kenny Youngblood, future National Dragster staffer John Jodauaga, and talented photographer Jere Alhadeff, had a knack for creative thinking. “I always liked to do something different,” he told me. “If you’re doing the same thing as everyone else, you’re in a crowd. How are they going to spot you?

“At the time, Revell had some model cars they made called Deals Wheels, which were all of these wild car designs, including a Vega, and I got the idea of the Vega panel truck that it would make a great deal for a sponsor that used delivery trucks, like a UPS or Federal Express kind of company, so I mocked one up,” he remembers. “It was actually Glenn who thought of Wonder Bread or Hostess. I tried three or four companies before we got to Wonder Bread, but they were really looking for an unusual program, and this was it.”

(According to Way, they also had solid interest from both Wrigley chewing gum and Burger King, but decided to go with Wonder.)

Kachler found an ally in another out-the-breadbox thinker in ITT’s Jim Anderson, who liked the idea. Kachler flew out to the company’s headquarters in Rye, N.Y., where an agreement in principle was made. He flew home to tell Way the good news.

“I told him they wanted to fly out to see the cars; Glenn went gulp, and said, ‘There are no cars yet; I was going to use the [sponsor] money to buy one.’ I was totally shocked. Fortunately, John Durbin put me together with Don Rackemann, whom he said wanted to get back into racing and could probably help.”

Rackemann had been a hot rodder since a young teen in the mid-1940s and had done everything from running speed shops and dragstrips to publishing; he knew everyone through his business, The Action Co., and knew how to talk the talk.

“Bob and I had been partners before, but when they laid this whole program out for me, I told Bob that I didn’t want to get involved without a name driver,” recalled Rackemann, now 84 and as full of spirit as ever. “Glenn had driven the fuel altered, but I really felt that if we were going to do a dog and pony show, we needed a bigger name, and that was Kelly Brown. We knew Kelly, knew he could drive and that he was a cool customer.”

Rackemann was able to purchase the ex-Stan Shiroma Midnight Skulker Barracuda and associated parts, pieces, and tools, and suddenly the team had a car. Don Kirby put together and painted the first body (which, the first time the Wonder Bread people saw it, was actually the fiberglass "plug" and not a real body). A second car would soon be built by John Buttera, with the original plan being for Brown to run the national events and Way, who had a regular 9-to-5 job in SoCal, would run the match-race scene.

|

Waiting for the dough to rise

Kachler and Rackemann flew back to New York, ostensibly to sign the contracts, but they were ushered into a meeting with someone other than Anderson.

“We’re sitting in this cubicle, and this guy was very evasive with us,” recalls Rackemann. “I said, ‘Wait a minute, are we signing contracts today?’ He looked at me and said, ‘No, I never said that.’ Now, Kachler is a pretty low-key guy, but he was pissed and ready to go over the desk at this guy. I reached behind him and grabbed hold of his coattails to stop him. We left without the deal, did some sightseeing in New York, and Bob went home. I stayed because I have a friend who has a boutique on Madison Avenue in New York, and I was looking for some new suits.

“Later that night, my phone rings, and it’s Jim Anderson. He tells me they’d like to revisit the opportunity. I told him I could be there about 11 or 11:30 the next day after I had my fitting. I showed up for my fitting at 9:45, but he’s helping this lady, and she’s just buying up the whole store. I’m looking at my watch because I have to get going. Finally, she gets done, and my tailor friend introduces me to her, and it’s Ethel Kennedy. We sat down and talked for a long time about everything for hours and forgot where I was supposed to be.

“I didn’t get out to Rye until 1:30, and the receptionist tells me they’ve been waiting for me in the conference room for hours. I could see Anderson was pissed. When they finally got everyone back together, I apologized for being late. ‘I’m sorry, but I was having breakfast with Ethel Kennedy, and I just couldn’t break away,’ I told them. They about crapped themselves, and we made the deal.

Brown, right, with ITT Board Chairman Harold Geneen.

|

“So it’s Friday afternoon, and we’re all shaking hands, and they said, ‘We’ll send you a check.’ I said, ‘Wrong. We have another company that wants this program. If I don’t leave here without at least $25,000, we don’t have a deal.' They told me they didn’t think they could find the treasurer, so I told them we had a deal set with Arby’s — we had sent them a package, but we didn’t have a deal yet — and they were ready to sign. They found the treasurer, and I got the check. That was the biggest cash deal in drag racing at that moment because [the Mattel] deal was for a piece of each car they sold.”

Once the first car was completed, it was sent to Rye, where ITT employees, including ITT Board Chairman Harold Geneen, got to see it for the first time. Brown even got Geneen into the car.

“He had probably never seen a Funny Car before,” Brown told reporter Deke Houlgate after the presentation. “He sat in the car, and we explained the controls to him. He asked very legitimate questions about the spoilers and aerodynamics. Not the sort of thing you expect from a businessman. The people standing around suddenly were smiling and obviously relieved. It turned out that he loves cars and owns a Maserati, which he goes ripping around in.”

Rough debut

(Above) The Wonder Wagon made its official debut at the 1972 Supernationals but couldn't crack the field. (Below) The team tried to cure the car's spooky handling characteristics with canard wings at the 1973 Winternationals. This is Jake Johnston in the second car. Neither car made the field.

|

|

Brown had quite a few hairy moments in the car, including this fire at OCIR. "I was worried about getting killed in the car," he later said. Brown sent me pages and pages out of his personal scrapbook to help illustrate this column.

|

The first car made its unofficial debut at Orange County Int’l Raceway in front of a full contingent of Wonder Bread executives.

“We’ve got the president and the vice president coming out, we have helmets and firesuits just like Kelly’s with their names on them, and it’s a really big deal,” recalled Rackemann. “The car had never even been down the track, so I tell Kachler and Kelly to just do an easy burnout, and if they want a parachute shot, just blossom it and drive the car slow. But their publicist tells them, ‘I really want you to smoke the tires and blossom the chute.’ Kelly nails it, the body comes down on the throttle, and he can’t shut it off and hits the guardrail and scrapes the right side of the car all the way down. We’re supposed to do a show at the Ambassador Hotel for all of the local division directors of Continental Bakery and all of the storeowners. Buttera doesn’t have time to fix it, so he told them just to park that side of the car against a wall and put stanchions all around the car so no one could get to that side.”

The car was repainted in time for its official debut at the 1972 Supernationals, with Brown driving. The car went 6.70 at 210 mph on its first pass but can’t crack the 6.51 bump spot. They ran both cars at the 1973 Winternationals (with Jake Johnston in the second car because Way did not have a license) but didn’t qualify and at a few other races, also with little success. As has been told many times by many people, the Vega panel body was not conducive to high speeds.

“We had a lot of handling troubles with them,” admitted Brown, “and we tried a lot of different things. The car would just get loose in the middle of the run. We put wings on it; Buttera even cut the back window out once to relive the pressure in there, but the chutes went into the back window when I pulled them.”

"I told them they had to louver the roof to kill the lift; they wouldn’t do that,” recalled Kachler. “Air going over the top of the car was low pressure; it’s going to lift the back of the car. I had studied aerodynamics, but they didn’t want to believe me, they didn’t want to do that." [The team did later add canard wings to the sides of the car.]

They had hired Ed Pink to do the engines, so they had plenty of power, but they were the only things that were running smoothly, at least in Kachler’s eyes.

“Rackemann was friends with Lou Baney — Jerry Bivens, who was Baney’s son-in-law, was the crew chief — and I felt like they really were beginning to take over the deal. I felt that they were really pushing Glenn out of the picture, and they wouldn’t listen to me about the car. I didn’t like the way it was shaping up. Rackemann agreed to give me $6,000 as a commission for finding the sponsor, and I left.”

Way tried to get his license at Bakersfield, but had problems with the brakes. Brown, meanwhile, soldiered on with the other car and got a little (ahem) toasty after he rode out a big fire at OCIR. On another run, vibration broke the throttle and the steering but got it stopped OK. The car actually reached the final round of the AHRA Northern Nationals at Fremont Raceway in Northern California before a blown engine stopped him.

“I got to thinking it was time for me to look elsewhere,” said Brown. “I loved those guys, but I was worried about getting killed in the car.”

|

"The Rack," Don Rackemann, still preaching his gospel at 79 (five years ago).

|

A bad ending, any way you slice it …

Things didn’t get any easier after that. What Rackemann didn’t know at the time is that NHRA worked with the Continental Baking group to bring out a lot of their representatives and dealers to the Supernationals at Ontario Motor Speedway, with a full-on suite and more, and the ITT folks used some of the race car budget to fund it, which Rackemann didn’t discover until he went looking for his second payment.

Coincidentally, Rackemann, who was doing well in other aspects of the business world, had purchased a new Ferrari Dino for himself in December of 1972, and it didn’t take long for people to start drawing lines between the missing money and the new Ferrari.

“Everyone got it in their minds that that was what happened, but it wasn’t,” insists Rackemann. “What people didn’t know was that I’d already put a lot of my own money into the car to have it fixed a couple of times. It was kind of frustrating, and I got tired of it and just said, ‘Screw it,’ and parked the car.”

The timing of this is roughly around the Gatornationals, shortly after the Northern Nationals outing. The car did not make it to its planned outing at the Gatornationals.

About this same time, the folks at ITT apparently caught wind of all of the bad vibes and called Kachler.

“I got a call from Jim Anderson, saying they loved the program but didn’t like the people running it, and he asked me for recommendations,” he recalls. “Don Schumacher didn’t have a big sponsor, and he took over the deal. Don was pretty upset with me at first, but I told him I didn’t fight against him, that they called me. We were able to remain friends throughout the whole deal and still are. Schumacher took over the deal, but he didn’t want to run the panel. He did, but he crashed it, too. The whole thing was a very sorry story. I feel sorry for Glenn because he started the whole thing, and I feel he kind of got pushed out.”

Way, who today takes part in Cacklefest events with his restored Groundshakers Jr. fuel altered, understandably remains "pretty bitter" about how the whole deal, his baby, was pried from his grasp. "It didn't take long for me to see that the whole deal was getting away from me," he said. "When they'd start to have meetings and I wasn't invited, it became pretty obvious. It all turned to crap right in front of me, and there was nothing I could do. The final straw was when I found out my pay was getting shorted, I decided I didn't want to have anything more to do with it. In hindsight, I just was not experienced enough to know how to do any of this and got steamrolled."

Enter the Don

Don Schumacher, left, with ITT's Larry Batly at a bakery display in mid-1973.

|

After the Vega panel body was shelved, the Wonder Bread colors went first onto Schumacher's Plymouth Barracudas (above) then onto Vega coupes. (Below) That's a pre-Blue Max Raymond Beadle in one of the Vegas.

|

|

There was a lot going on for Schumacher in 1973. He had expanded to three cars in 1973, adding a pre-Blue Max Raymond Beadle in the ’72 car along with he and Bobby Rowe (who left the team early that year and was replaced by Ron O’Donnell). Schumacher won already both the NHRA and AHRA Winternationals, the AHRA Northern Nationals, and an AHRA Tulsa Grand Am event in a yellow Stardust Barracuda on the way to the AHRA championship. He remembers exactly when and where he was when he got the call from Anderson.

“I was sitting in a hotel room in Tulsa [Okla.] when I got the call,” he said. “I kinda shrugged my shoulders. I actually thought it was a bit of a lark at first. ‘OK, send me an airplane ticket, and I’ll come out there.’ I, of course, had seen the cars earlier that season and thought the idea was really cool. I knew they weren’t running well, but I thought that was because of the overall operation they had, not necessarily because of the body.

“The whole program was a tool for the actual salesmen who went store to store in the bread trucks and stocked the shelves, so they could attract the store managers to come out to the races, ply them with hats and tickets to help make sure that their bread was put on the shelves at eye level [to the shopper],” said Schumacher. “I thought it was a great idea.

“I flew out to New York and took the train out to Rye and put the deal together for a three-car team: My car would run the NHRA, AHRA, and IHRA national meets and whatever match racing I could fit in; Bobby Rowe’s and Ron O’Donnell’s car was going run the Coca-Cola Cavalcade of Stars circuit; and Raymond’s was a match-race car.”

Schumacher took delivery of three wagon bodies, with the first mounted on the chassis of his successful Stardust machine. Schumacher debuted the car at a match race at Great Lakes Dragway in Union Grove, Wis., but it only took him one run to change his mind about the body.

“I got 400-, 500-, 600 feet into the run, and the car just came loose and went crazy; I almost turned the car over,” he remembers vividly. “I said, ‘That’s it, these things won’t work.’ It was clear that the body just didn’t have the aerodynamic characteristics to go down a racetrack. I sent my guys back to our shop in Park Ridge, Ill., to get the Barracuda body and finished the race with that body.” (In an interview I did with Schumacher a few years ago, he had told me that the panel-wagon-bodied car had, “all the aerodynamic qualities of a desk.”)

“We were all very naïve aerodynamically back in those days,” Schumacher admitted. “Even today, racers tend to think they know what’s going on aerodynamically until you get an aero engineer involved. We were all just kind of guessing about what we thought we should do.”

Schumacher, being a savvy businessman, had the foresight to have it stipulated in the contract that if the panel wagon did not work, he could go back to a conventional body, which he did. Although the idea of a bread-wagon race car was (ahem) shelved for good, a panel-wagon version sometimes made non-racing appearances before match races with Way -- whom Schumacher had graciously hired-- shepherding the car.

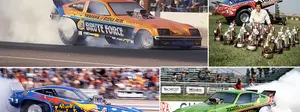

The Barracudas were all painted in Wonder Bread colors, as were a couple of standard Vega coupe bodies that followed. The crowning touch — and the best-remembered part — of the Wonder Bread program was the super-trick, aerodynamic Vega that Schumacher debuted at the 1973 U.S. Nationals. It was awarded the Best Engineered Car honors, and although it never lived up to its looks, it nonetheless got people thinking.

Highlights of the swoopy Wonder Wagon were a flow-through grille, hood, fender blisters, and rear window, as well as side windows and Moon-style wheel covers.

|

|

Learning to fly

Built by famed fabricator John Buttera at his shop in Cerritos, Calif., the low-slung slot car looked fast even standing still. It was 3 inches lower in the front and 5 inches lower in the rear than any previous Vega Funny Car. Buttera also reclined the driver position an additional three degrees, which, in effect, lowered the top of the roll cage some 9 inches. The driver actually sat so low in the chassis that Schumacher often couldn’t see the staging lights on the Christmas Tree, so a Lexan window was cut into the roof to help his vision.

The body that cloaked the chassis most definitely was unlike any other out there. It was built using an existing Vega body with heavy modifications. Louvers cut into the hood allowed air to pass through the working grille of the flat-nosed body — Buttera used the actual grille from a production-line Vega — and onto the hood, meaning that the air first did not collide with the nose but moved through the car and up onto the hood, supercharger, and windshield, which aided downforce in the process. Any other air trapped under the body exited through a louvered rear window, again to dual benefit: Air trapped under the body was lifting the rear wheels and directing it right onto the rear spoiler. With this direct flow, Schumacher and crew chief Steve Montrelli were actually able to use a smaller rear spoiler.

The body was made even more slippery with fully enclosed side windows — a given today but outrageous back then — and an outrageous hood bubble that covered the supercharger. Front fender blisters — which had come into vogue the previous year to lower the body around the tops of the front tires — were enlarged and vented in the rear to help trapped air escape. Moon-style disc wheel covers also aided the aero package.

“The car definitely wasn’t as successful as I hoped,” admitted Schumacher. “It’s a shame we didn’t have a wind tunnel and a shame we put so much weight in the body by just altering a body and not building a new one. The car was nearly 400 pounds heavier than any other car. The principles were phenomenal, but it was really my fault for asking for a stiff car. I had Buttera build the car with a stiff chassis because of all of the [match-race] dates I used to run; I got tired of rolling the car out of the trailer and finding something broken. We didn’t know how critical it was to have a flexible car. It just didn’t react well.”

Although Schumacher’s efforts certainly brought new luster to the Wonder Bread deal, the Continental Baking group pulled out of their sponsorship before the start of the 1974 season, and Schumacher retired from driving at the end of that season and remained out of the sport until son Tony began racing in the mid-1990s.

Wrapping it up

It’s really a shame that the Wonder Bread deal was so short-lived and, with its rocky start, never was able to make the kind of full impact it could have, which might have led to more similar deals and helped build a better sport in more ways the bread’s famous “eight ways” slogan.

“Without a doubt, I really believed that having Wonder Bread in the sport was going to be the start of having a lot of non-racing sponsorships in the sport,” Schumacher said.

Kachler, too, mourns what could have been, including the great idea they had conceived for a television commercial that begins with an outside shot of an industrial building.

|

“You hear the sound of the door rolling up, then you hear an engine start, and the car rolls out of the door and drives past, and in the back window were little loaves of bread,” he tells me, his voice still filled with, well, wonder, at the thought. “Kelly would do a burnout, and then we're going to do a planned shoot of the car going 200 mph down the freeway, then coming down an off-ramp and rolling to a stop in front of a supermarket, headers still cackling and popping. Kelly, still in his firesuit, would go to the back of the car and come around the other side with a tray full of bread. He walks by this guy who’s hosing down the sidewalk at the store, and the guy says, “Good morning, Kelly … I see it’s still fresh to you every day,’ and Kelly says, ‘You bet!’

“Unfortunately, it never got made. It would have been one of the great commercials of that era. It could have done so much for the sport because people would have seen how dynamic it is — the noise, the color, the crowd.”

So that’s it, friends and bread lovers. I hope you enjoyed this little slice of drag racing history. More next week.