Rocket roundup

|

In the interest of full disclosure – and many of my longtime column readers know this already – the two-part story on “Capt. Jack” McClure’s rocket go-kart was a long time coming. I did the interview about a year ago and – shame on me – sat on it for a few weeks while working on other columns. I thought I was the only one who had “found” him after all of these years, so I thought my “scoop” could wait while I put the pieces together.

I didn’t realize that McClure had a Facebook page, and before I could get my story online, he also had done an interview with another website; when that interview was quickly published, quite a few of the quotes were similar to what McClure had given me, so I felt I needed to distance my story from the other so that no one thought I was riding on its coattails. I felt bad for McClure, who had spent considerable time on the phone with me, but he was understanding.

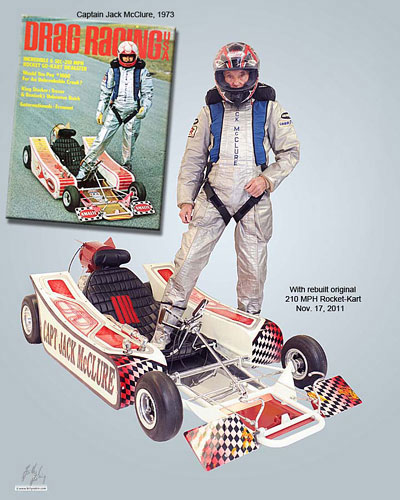

We had exchanged a few emails in between, and I got a note from him earlier this week after my recent two-parter, thanking me for its thoroughness and accuracy, but because – again, shame on me – I had not followed up with him, my last column ended with the whodunit concerning the kart’s whereabouts when, in fact, he not only had since found it but had it restored by Ky Michaelson, as you can see here in his photo, in which he has re-created the Steve Reyes photo from the cover of the July 1973 issue of Drag Racing USA.

“I found out that Ramon's [Alvarez] daughter had it, and it took a long time to make a deal,” he said. “I didn't want to tell anyone where the kart was, but I had it and was waiting for when it was restored. Anyway, I got it back and took it to Ky's shop in Bloomington, Minn., and he restored it."

“I found out that Ramon's [Alvarez] daughter had it, and it took a long time to make a deal,” he said. “I didn't want to tell anyone where the kart was, but I had it and was waiting for when it was restored. Anyway, I got it back and took it to Ky's shop in Bloomington, Minn., and he restored it."

The kart was disassembled and the frame sandblasted and repainted. Michaelson went through the propulsion system, and everything was chromed or polished, repainted, and reupholstered. The kart was then reassembled and the propulsion system test-fired last November.

"When we restored the kart, we did it with intentions of running it again," said McClure. "We installed new bearings, new heim joints, and new tires. Ky wasn't sure if the motor was in running condition; he had some 90 percent hydrogen peroxide, and we fired the engine; it worked like new. The problem is rocket-grade fuel; we found a source here in the U.S., but it's very expensive."

Even if they do get it run-functional, I'm not sure where they would run it. I'm sure it's not legal for any kind of NHRA applications, but you can check out a gallery of the kart’s resurrection at right, and there’s a lot more to be found on McClure’s new website (also built by Michaelson) that includes photos from McClure’s wild and vast career, a great interview he did with Michaelson that goes places my interview never did, and so much more. Check it out here.

There isn’t a ton of McClure footage around, but the BangShift group did copy this 14-second silent clip that gives you an idea of how the kart looked and ran.

McClure’s site also has a bizarre 14-minute, 42-second video clip of him running at Fremont Raceway in 1973 (when it was under AHRA control). That footage, shot by NorCal drag film mavens the Jackson brothers, shows McClure suiting up, consulting with his crew and track officials, and firing off into the dark Bay Area night trailing sparklers, but that’s shown over and over in an endless loop. I’m not sure who spliced this all together in this fashion, but you can pretty much stop watching after the 90-second mark. (You can thank me now for giving you back 13 minutes of your life; I had to watch it all just to make sure.)

Still, if you’ve never seen a rocket car run, even the small amount of footage here gives you an idea of just how quickly these things left the starting line. You’d be standing there watching the driver stage, maybe notice a little vapor percolating from the engine area, and then – WHOOSH – it was gone. As a kid, it was one of the most astounding things I can remember seeing at the drags (Leapin’ Larry McNemany excepted). The conventional rocket dragsters ran bigger engines than the one in McClure’s kart and ran well into the fours and more than 300 mph long before the first Top Fuelers ever did.

|

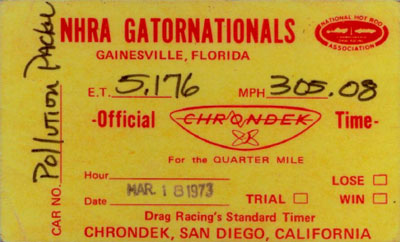

Speaking of 300 – and with the O’Reilly Auto Parts NHRA Winternationals presented by Super Start Batteries just around the corner – Bruce Lee, a friend of Michaelson’s, sent me a photo of one of his prized possessions: the first 300-mph NHRA time slip from a pass at Gainesville Raceway. No, we’re not talking about Kenny Bernstein’s 1992 history maker, but the 305.08-mph blast recorded by the late Dave Anderson and the Pollution Packer at the 1973 Gatornationals. Michaelson owned the Pollution Rocket car at the time it set these records. The car, sponsored by Tony Fox's trash compacting business (Fox later bought the car), was the first licensed rocket car to run on an NHRA track. Anderson had blown everyone away with a five-second, 297-mph run at the rain-plagued Winternationals, then made history a month later (on March 18 to be exact) in Florida. At the time, NHRA had placed a 300-mph limit on rocket cars --according to Michaelson, they were given a 3 percent margin for overun -- so from that point until the restrictions were lifted, the cars were intentionally run out of fuel early to avoid “breaking out.”

Anderson and Michaelson then wowed everyone a few months later with the first four-second pass, a 4.99 at the Springnationals in Columbus, and later ran as quick as 4.62 (in Indy) and as fast as a mind-boggling 368 mph (location unknown) before being killed in an accident the next March in Charlotte. Anderson held that speed mark until stuntwoman Kitty O’Neil ran 3.22 at 412 mph in 1977 on a quarter-mile track laid out at El Mirage that might not have accurately clocked her speed, but DragList reports that she also ran 392.64 on a sanctioned strip. DragList also reports that Vic Wilson drove Bill Frederick's Courage of Australia rocket dragster to a 311.41-mph pass during a private test at Orange County Int'l Raceway Nov. 11, 1971, but Anderson’s pass was done in public, so I tend to give it more weight.

The early to mid-1970s were definitely the golden age of the rocket cars but, with the exception of “Slammin’ Sammy” Miller, largely fell out of favor by the early 1980s. Of all of the things I’ve seen and done on this job, perhaps one of my weirdest claims to fame was that I actually served as a crewmember on one of the last rocket cars during my first year on the job here, way back in 1982. Those first years here I was kind of like a kid in a candy store, wanting to run around and do anything that gave me an inside look at the sport, which included working as a crewmember on various cars and, of course, driving the Mazi family blown altered.

But in 1982, I had become fast friends with Brent Fanning (well before his inexcusable starting-line stunt in Indy with his nitro Funny Car), a dairy farmer from Stephenville, Texas, who had built his own unique rocket car. It was short-wheelbased and could wear either a Funny Car body (a topless Corvette) or a homemade “altered” body. He’d be booked into a track to run in either guise (or sometimes both); the Funny Car was called Outer Limits, and the altered was Concept-1. Larry Bostick, a fearless 28-year-old from Lingleville, Texas (population 78, according to their press materials), drove the car.

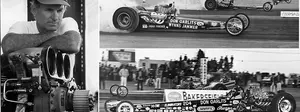

Some rookie reporter, center, with Bostick, left, and Fanning, standing in front of the Outer Limits Corvette in the Sacto pit area. I still have that shirt.

|

I had made acquaintance with them at OCIR, during the 1982 Summer Showdown event, one of the first I ever covered for ND. We kept in touch, and that September Brent invited me to travel with him and Larry to run at the Governor’s Cup event at Sacramento Raceway. They’d already been rained out there the first try, then drove home (1,700 miles) and two weeks later picked me up in Los Angeles on their second trip (they’d left the car at the track). We were about six hours into the seven-hour drive north when we received word the event had been rained out again. Fanning debated just picking up the car and calling it quits (which meant he would have been out his $750 appearance fee) or turning around, heading home, and coming back three weeks later to run the date, which we did. The disappointment and lost highway miles gave me a firsthand glimpse of the not-so-fun side of match racing.

I learned a lot about the car and rocket racing. The altered weighed just 750 pounds and sported a 3,500-pound thrust (about 6,000 horsepower, they reckoned) engine. With the Funny Car body, it weighed 1,050 pounds – still pretty light! DragList credits Concept-1 with a best pass of 5.22 at 270.27.

The Concept-1 rocket altered. Sparklers were just for show, and we also had matching ones on the chase vehcile that were fired off on the return road.

|

Anyway, the second trip to Sacto was successful, and we (yes, we) ran 5.92 with the Outer Limits and 5.67 with Concept-1 – certainly not world-beating runs, but Fanning and Bostick were pretty pleased. I chronicled our adventure in an article I wrote for the late Stevie Collison for Super Stock & Drag Illustrated, but he never published it. Looking back at the writing in my rookie year, I can see that it certainly wasn’t Cole Coonceian in its prose, but I still liked it and got a kick out of rereading it yesterday and reliving those memories. Stevie was nice enough to send me back my story and – even better – my negatives, so that I could show you the photos here.

I stayed in touch with Fanning through early 1983, but the increased cost of bookings (due to fuel bills) led to a major reduction in bookings and even led him to construct a wall made of ½-inch-thick Styrofoam to be placed at the 1,000-foot mark with an opening for Bostick to try to drive through; the opening was just 2 feet wider than the car (“making impact unavoidable” he noted). They tested it, but I don’t think anyone ever booked it.

That March, I got a note from him reporting that hydrogen peroxide manufacturer/distributor FMC had informed him that it no longer would be making the product. ”This means no more rockets,” he wrote, sadly. “The entire rocket system in our car is now worthless. We should be able to get a few more barrels of their closing stock … but our days are numbered.”

And so the rocket car, another part of drag racing’s wild and woolly past, was resigned to history. As much as I liked to watch them run, with their otherworldly speed, that’s probably not such a bad thing.