Roaring with appreciation at the Lions Reunion

|

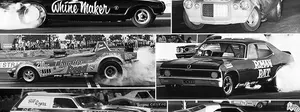

Compared to its Fancy Dan contemporaries Orange County Int’l Raceway and Dallas Int’l Motor Speedway, Lions Associated Drag Strip was a dust bowl wedged between freeways and refineries. Yet Lions left an indelible impression in the hearts and memories of the legion of faithful who called “the Beach” their home, which goes a long way toward explaining why several hundred people turned out on a rainy night last Saturday at the Wally Parks NHRA Motorsports Museum to reminisce about one of Southern California’s most storied tracks.

An all-star cast of panelists – coerced and cajoled by co-emcees Dave McClelland, the longtime voice of the NHRA, and museum curator Greg Sharp – entertained and enthralled a roomful of listeners that also was high in star appeal, from legendary Art Chrisman to newly crowned NHRA Funny Car champ Jack Beckman.

The panelists – broken into two groups that each spoke for about an hour – included some of the sport’s biggest names in Don “the Snake” Prudhomme, Tom “the Mongoose” McEwen, “TV Tommy” Ivo, “Big Jim” Dunn, and Roland Leong, as well as a phalanx of famous Lions names such as injection wizard Gene Adams, engine builder Ed Pink, gasser great “Bones” Balogh, Top Fuel ace Gary “Mr. C” Cochran, and car owner Mike Kuhl, whose Carl Olson-driven dragster won Top Fuel at Lions’ Last Drag Race. The panel was not limited to drivers as both Lions biographer Don Gillespie and former track photographer John Ewald (J&M Photos) also shared memories of the facility and its two most famous operators, Mickey Thompson and C.J. “Pappy” Hart.

There were plenty of memorable reunions at the Lions Reunion, including of panelist Don "the Snake" Prudhomme, right, and Tommy Greer, who teamed on the famed Greer-Black-Prudhomme Top Fueler of the early 1960s.

|

Although Lions didn’t have a fancy timing tower like OCIR and DIMS, it had the one intangible that a contractor can’t cement into place: magic. Panelist after panelist explained his love affair with Lions, talking about how each Saturday night, the place was electric with anticipation, and the pits were packed with the region’s – and sometimes the nation’s – finest racers. For many, it was kind of like that bar in Cheers, a place where everyone knew your name and you knew theirs, from the ticket takers to the concession-stand workers slinging the notorious chili-covered tamales. Every Saturday night was a battle royale, and when the famous fog rolled in late at night, anything could happen.

Compared to running at other local tracks, Prudhomme said that going to Lions was like going to Yankee Stadium. “It was the all-time coolest place ever,” he said. “It was a special place.”

“Lions wasn’t a drag race,” echoed Cochran. “It was a happening. Lions Saturday night is where everyone was."

“We got pretty spoiled every Saturday to go to Lions and see cars that the folks back East only read about or saw in pictures, and they were all there every week like a regular deal,” Sharp agreed, and, noting the quantity and quality of the competition at Lions each week, Ewald added that for many, “Winning a trophy at Lions was like winning an Oscar.”

Pink added, “I loved the place. The track was nice and smooth, and the air was great. For an engine builder, you love that kind of track because you could make as much power as you could. You could pretty well put the can in it and, within reason, run it as hard as you could.”

'Twas truly a special place, and it was a special treat to hear them all reminisce about the place. Here are some of the more memorable exchanges of a magical night.

Many commented about the track’s special atmospherics, at sea level with the cool ocean air flowing in at night accompanied by a fog, which led famed Drag News correspondent “Digger Ralph” Gudahl to coin the phrase “the duels in the dew.” Cochran recalled that the fog sometimes was so thick that drivers launched into the night and couldn’t see the finish line until they were at half-track, and even then, vision was somewhat limited. “You knew if the front tire started bouncing, you were in the gravel and you needed to move over a little bit,” remembered McEwen. Doug Dryer, who mounted a lot of the nitro tires back in the day and was part of the audience, related a quote attributed to Funny Car racer Neil Lefler: “Drive into your garage with the lights off at 100 mph and stop before you hit the bench."

Balogh recounted one of master showman Thompson’s stunts, a Le Mans-style start during the “lunch break” between runs in which drivers had to run from their cars to the spectator fence then back again, snatch their keys off the hood, start their cars, and race to the other end. “I had a hard time finding the key, so I asked Mickey if we were going to do it again next week. ‘Oh, yeah; the crowd liked it.’ I said, ‘Good,’ [and put in] a toggle switch and a push button.”

Thompson certainly earned Prudhomme’s respect – and instilled fear. “We were down there at the end of the track, waiting in line to get water for the engine,” he said. “Mickey Thompson was running the place at the time – he was a big deal, y’know – and someone in line was giving him [grief], and, lo and behold, he just reached over and knocked the guy plumb out. I thought, ‘Holy cow!’ It scared me to death. He threw me out once because when I was driving Ivo’s single-engine car, I put a parachute on the back – it didn’t really need one, but Ivo had one on his twin, and I thought it would be cool to have one on my car – but it put too much weight on the back and did this big wheelstand. Mickey came up to me and said, ‘I’ll throw your ass out of here if you do that wheelstand one more time.’ We went back and put some weight on the front end, but it didn’t help, and, sure enough, he threw me out of there for six months. That was Mickey; he was a tough son of a bitch.”

Tom "the Mongoose" McEwen, right, chatted with his former car owner, Gene Adams. They teamed on the Albertson Olds entry in 1961.

|

Adams recounted the brief but spectacular history of the Albertson Olds dragster at Lions, a six-month period in which he and driver Leonard Harris won 12 straight races sandwiched around a win at the Nationals in Detroit; that partnership ended with the sad demise of the extremely talented Harris at "the Beach" while test-driving a car for another racer. “I guess I had some of my greatest and worst moments there,” he acknowledged.

At times, the proceedings took on the flavor of a roast. With the microphone his, the ever-energetic and evil-grinning Ivo let his buddy “the Mongoose” have it pretty good.

“McEwen’s nickname was 'Cassius,' after Cassius Clay. That was because his mouth ran faster than his car did. I used to love racing McEwen. At that time, Gene Adams was his mechanic. You know, good ol’ kind, easygoing Gene Adams – NOT. He’d get down to the other end if they lost and throw the toolbox out of the back of the truck and chew McEwen up one side and down the other. That show was better than going to the circus.”

And he didn’t let buddy Prudhomme, who began his career as a helper on Ivo’s cars, off easy, either. “Back then, he was just a garden worm, not ‘the Snake,’ and he had the darnedest laugh you ever heard. If something struck him funny, he would laugh so hard that everyone around him would be laughing because it sounded like a cross between a constipated hoot owl and someone being choked to death.” He then proceeded to give his impersonation of such, to the howls of delight from the crowd.

Dunn also had a great McEwen story: “I’d like to thank the guy who gave me the biggest help in tuning a nitro car,” he said. “I was running the Dunn & Yates car; we had just started and only had 75 percent in it. We got a chance to race McEwen. In those days, you’d flip a coin to see who got lane choice. I think he was driving for [Lou] Baney then, and I asked him, ‘Tom, you wanna flip for lane choice?’ [and he said], ‘Kid, take the side you want because there’s no way you can beat me.’ That was the wrong thing to say to this Okie boy. I go back and tell Al what [McEwen] said, and he said, ‘Drain the tank and put in 90 percent.’ I have a nice picture of me winning, and I got from [running] 75 to 90 percent in one run.”

Dunn also noted the difference between racing then and racing now. ”If two of you had a job, you could run a fuel car because you’d win $25 for first round and be able to buy enough nitro for the whole next race. Now, if you want to go to Indy, you’d better have $700,000 to get everyone there.”

Dunn also recounted a match race that he ran with his altered at Lions in which three-quarters of the stands were filled, a feat of which he was proud until Hart told him, “Dunn, I can get two guys on roller skates and fill half the stands.”

|

The Dec. 1 reunion also marked the 40th anniversary of Lions’ Last Drag Race (Dec. 2, 1972), and that raucous night was the subject of extended remembrances about the free-for-all nature of the evening’s final moments, when spectators climbed onto (and, in some cases, began disassembling) the guardrails, and rocks and bottles were heaved onto the track (Olson distinctly remembers crunching over several bottles on his winning pass against Jeb Allen). “It was pure chaos; all of the security guards had left an hour earlier,” confirmed Kuhl. “It took us about an hour just to get back up the return road to the starting line after we won.”

Kuhl also confirmed Olson’s story about not wanting to run the final that night because of the unruly crowd and because, by that point, their two-race-old car had literally shook itself to pieces and was partially held together by baling wire. “I told Carl, ‘The worst thing that will happen is that the motor will fall out of it and it’s behind you, so who cares?’ We crossed our fingers, and it worked.”

According to Sharp, track manager Steve Evans got a call during the night from partner Bill Doner asking about the crowd. “I’ve got about 1,500 people,” Evans told him. “Fifteen hundred people? That’s all?” asked an incredulous Doner. “Yeah, in the photographer’s area,” replied Evans.

Sharp, addressing Prudhomme, spoke about how “the Snake” got his start in Ivo’s dragster at Lions and asked, “How’d it go from there?” to which Prudhomme perfectly deadpanned: “Well, apparently, it went pretty good.”

Leong recounted his now-famous tale about his one-run Top Fuel career that ended with him off the end of the Lions track and led to Hart yanking his license and Keith Black refusing to run with him anymore because he was scared for Leong’s safety. That, of course, led to Leong – on Black’s advice -- hiring Prudhomme to begin their legendary 1965 season together. As they headed out on tour that year, the rookie fuel tuner and his new shoe, Black’s pessimistic observation was, “The blind leading the blind.”

Asked by McClelland why he had gone through 22 drivers in his years, Leong replied simply, “I guess I’m hard to get along with.”

(Above) From left, Lou Baney, Ed Pink, and McEwen huddled around the SOHC Ford powerplant in the Brand Ford Special dragster (below) in 1967.

|

|

(Above) Baney and Prudhomme shared a laugh over the same engine after "the Snake" replaced "the Mongoose" in the car at midyear, then won the NHRA Springnationals in Bristol (below).

|

|

"The Snake" and the cammer

|

One of the evening’s great exchanges was between McEwen, Prudhomme, and Pink, for whom both drove. As a matter of fact, Prudhomme replaced McEwen at the wheel of the Lou Baney-owned Ford cammer-powered dragster owned by the SoCal car dealer, which led to a series of “Let’s set the record straight” stories.

To back up a bit, Pink explained that the famed SOHC engine, with which he, Connie Kalitta, and Pete Robinson enjoyed great success in the mid-1960s, was designed by Ford for NASCAR competition and with just 750 horsepower on gas and carbs and not for high-powered nitro drag racing. Once Ford realized that the NASCAR rules would saddle any Ford SOHC-equipped car with a weight penalty, it turned to Pink to try it in drag racing. Pink, with his engine-building business, was the perfect guy to help expose it to the quarter-mile masses. But there were complications. For one, it oiled like crazy – usually the driver. And it was harder than a conventional Chrysler to work on.

“The Ford made more power, but it was too hard to work on,” Pink explained. “With the overhead cam on top of the head and that 6-foot timing chain, it was a lot more work and a bigger chance of an error. It really thundered, though, and made power in the right spots."

At which point McEwen self-promotionally chimed in, “You had to have a good driver in it, too …”

As McEwen tells the story, he had been driving for his good pal Baney for a while with Chrysler power, but when Baney’s dealership switched from Chrysler to Ford, it was only natural that his race car should, too. McEwen paid the oil-bath price on many an off-pace run but got fired from driving the car because he tried to compensate for the car’s performance and red-lighted quite a bit; he added that “the Snake” got the ride just as the engine was coming into its own and hopped right in and won the 1967 Springnationals with the car.

“I was like the oildown test pilot of this car. It had oil coming out of every crease. I had to wear three pairs of goggles just to make a run. It didn’t run good, it missed, so I started red-lighting because I couldn’t beat anybody. Just about the time he got the car running good, he fires me, hires this kid over here [Prudhomme]; they go down to Bristol and win the Springnationals, and everybody was happy. That’s the real story.”

Pink rebutted, “To start with, there were some problems with the Ford cammer, and it did oil, and we had the right guy in there at the particular time. I was at dinner one night with Baney, and he told me McEwen quit and asked who we should get. I said we probably ought to get Don Prudhomme because he was available. I said, ‘Are you sure McEwen quit?’ and he said, ‘Yes, the car was scaring him because it was going too fast and made his nose bleed.’ "

McEwen fired right back, reminding Pink of Prudhomme’s prior success with rival engine builder Black all the way back to the Greer-Black-Prudhomme car. “Let me tell you, ‘the Snake’ and Keith Black beat you so many times that your dream was to have Prudhomme drive for you …”

Not one to take his termination lightly, McEwen vowed revenge. “After they fired me, I’d have someone sit outside their house when they’d leave in the morning and tell him to call me and tell me which track they were going to,” he said. “I’d get in whatever I was driving, and we’d go wherever they did and try to beat them, but it was tough to do because that cammer ran really good, and he [Prudhomme] drives fair.”

Prudhomme, who had been rolling his eyes throughout the exchange – Pink was seated between the two – got a good laugh from the crowd, too. “Back in those days, Pink sort of had a short fuse, and so did I. That cammer Ford hauled ass, but it did leak pretty good. Pink’s engines were really beautiful, and the car was gorgeous, but I’d get down to the end of the track, and my goggles would be all oiled, and I would just hand my goggles to Pink. That really pissed him off.”

|

McEwen then thanked Pink for letting them drive the car. “Driving the cammer really made Don and me,” he said, and you could just tell the arrow was loaded. “After driving that car, you could run anywhere, night or day, lights or dark, it didn’t make any difference because we learned you could drive without seeing anything.”

In addition to display cases full of Lions memorabilia and photos, one of the visual highlights was Rick Voegelin's HO-scale replica of Lions, complete from the trademark crossover bridge to the signage on the walls with slot cars and a full timing system. The audience also got to see a trailer for the forthcoming Snake & Mongoose movie and heard from producer Robin Broidy and had the chance to win cool Lions door prizes.

All in all, it was a magical night to remember a magical place.

The Lions Reunion panelists: front row, from left, Mike Kuhl, Roland Leong, Tom McEwen, Ed Pink, and Don Prudhomme; back row, from left, Jim Dunn, "Bones" Balogh, John Ewald, Tommy Ivo, and Gary Cochran

|