1982 Indy: The Nitrous Nationals (or not)

|

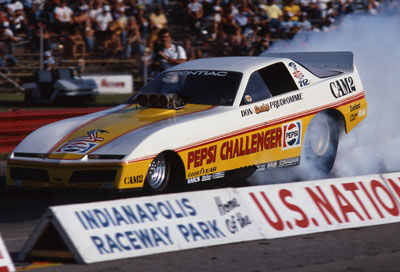

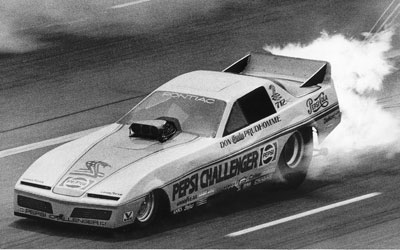

This year’s Mac Tools U.S. Nationals presented by Auto-Plus will mark the 30th anniversary of one of the greatest Funny Car runs in drag racing history, Don Prudhomme’s stunning 5.637-second blast during qualifying at the 1982 event. Even though cars today are more than a second and a half quicker, to me – and many others – it’s still the all-time-best run in class history.

(Some inevitably will point to Jack Chrisman’s surprising 7.60 at the 1967 Nationals as the greatest Funny Car pass ever. It was, after all, three-tenths quicker than the previous best run in the class, nearly seven-tenths quicker than Tommy Grove’s 8.34 national record, and nearly a half-second ahead of eventual winner Doug Thorley’s No. 2-qualified 8.16, but, to me, the class was still in its infancy then and the cars nowhere near as regimented and similar as when Prudhomme made his run. I’m sticking with the 5.63.)

Prudhomme was not the only performance star of the meet. Tom Anderson drove Jim Wemett’s Mercury LN-7 to a shocking 5.799 early in qualifying to become the first in the 5.7s. Eventual winner Billy Meyer was third at 5.814, 252.10, and “the Wizard of Wadsworth,” former alcohol ace Ken Veney, was fourth with a 5.84, 250.69 from his privateer Trans Am dubbed the Red Rocket. Twelve drivers qualified in the fives, and Paul Smith’s 6.03 set the record bump, six-hundredths better than the previous mark set in Indy the year before. Before the event was over, nitro neophyte Veney – with less than a dozen runs on nitro under his safety belts entering the event -- would shock the crowd and his peers with eliminations runs of 5.78 and a sensational 5.73 at 254.23 to set the new speed record.

It’s important to set the stage and put “the Snake’s" run – hell, the entire 1982 Funny Car field, for that matter – in context. Even though Prudhomme had made the first five-second run seven years earlier, at the 1975 World Finals, five-second passes did not become a commonplace occurrence for years. It wasn’t until April 1981 – more than five years after Prudhomme became the first – that all eight spots in Cragar’s Five-Second Club for Funny Cars were filled. The national record entering the 1982 season was 5.89, set by Dale Armstrong in his driving swan song at the 1981 World Finals at Orange County Int’l Raceway and 249.30 by Raymond Beadle in the Blue Max. Beadle also had run 5.86 in the Blue Max at the 1981 Summernationals but had not backed it up for a record.

In May 1982, Prudhomme’s sleek new Pepsi Challenger became the first Funny Car to break the 250-mph barrier at the Cajun Nationals. Two months later at the Summernationals, Meyer pummeled the Raceway Park timers with a 5.82, 254.95, which was top speed of the meet, faster than the fleetest Top Fueler. The .82 became the new national record, and Meyer’s 250.69 from earlier in the meet was backed up by the 254 for the new speed standard. Although Meyer was the performance star, Prudhomme won the race.

The sudden performance surge seemed to be the result of the injection of nitrous oxide into the fuel-delivery sequence. One question has remained throughout the years: Who used nitrous and who didn’t?

I burned up the phone lines the last two weeks reaching out to all of the parties involved to try to get the answer and recollections about that amazing weekend and to attempt to craft the definitive narrative of the situation.

|

Indy 1982 started with a bang Thursday as Prudhomme blasted to a 5.82 at just 242.58, setting the stage for a performance parade that followed. The next afternoon, at about 1, Anderson booted Wemett’s entry – cloaked in Budweiser King colors (we’ll get to that) – to a 5.799, the class’ first 5.7-second pass. The glory did not last long: Less than a half-hour later, Prudhomme stormed to a 5.73 at just 223.22 mph as the engine blew 100 feet before the first light. Stunned fans and fellow competitors could only theorize about what would have rung up on the timers had he been able to leg it through the eyes.

They didn’t have to wait long to find out.

Jon Hoffman

|

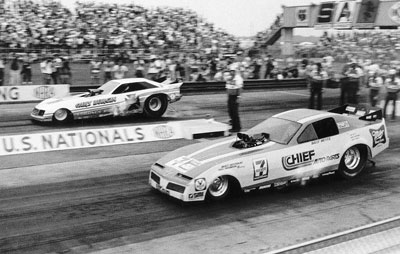

In Saturday’s second qualifying session, Prudhomme pulled up alongside Kenny Bernstein and train-lengthed the Budweiser driver to the stripe. Announcer Dave McClelland, a master in building drama, announced Bernstein’s time first: 5.90. Prudhomme’s time took away everyone’s breath: 5.637 at 244.56, nearly two-tenths quicker than the incoming best and a run that would have qualified fifth in the Top Fuel field.

So, was “the Snake” running nitrous? Nope. That he was running nitrous was so widely reported and has gone so largely uncorrected that it has become fact, but it's fiction.

Even though there was a clearly plumbed line running from an nitrous bottle to the fuel pump – and the team made a great show of “turning on” the bottle on the starting line in front of everyone – and even though they had done basic experimentation with nitrous in testing, Prudhomme and crew chief Bob Brandt most definitely were not running nitrous in Indy. The bottle was empty, the system a ruse.

The fake setup was a smoke screen to mask the new vane-style aircraft fuel pump – as opposed to a traditional gear pump -- that the team had begun running recently. A week before the event, at a race in Salt Lake City, Prudhomme had destroyed the track record and outrun everyone by two-tenths with outrageous numbers at the altitude facility.

“We had a lot of compression on it and a really good blower, but the difference was the pump,” he said. “The car just hauled ass. [Tom] McEwen couldn’t believe it – he said the clocks must be jacked up – so I told him, ‘When we race tomorrow, you just go ahead and try to drive around me, and I’ll show you it’s for real.’ And we did.

“We used to get a lot of fuel-system stuff – fittings and stuff like that – from those Army surplus stores. We were really involved with our engines – contrary to popular belief, I knew a little bit about them, you know? – and always trying different things, and the fuel pump was one of them. We were really into it; people don’t realize that.

“Anyway, we knew it was going to really haul ass at Indy because the pump just happened to have the right fuel curve. It would deliver the right amount on the bottom end and taper itself off at the top end without even using a jet. We lowered the compression a little bit for Indy, but we knew we had to do something so people wouldn’t know what we’d found, so we hooked this fake nitrous bottle right to the pump.”

(Armstrong certainly was not fooled. “I looked at it at the time, and the bottle was plumbed right into the fuel pump, which would be like sticking an air hose into your fuel pump,” he said. “It would be terrible and also easily over-pressurize the fuel system.” Meyer, similarly, was not fooled.)

|

Prudhomme’s Achilles' heel turned out to be the wrist pins, which were breaking on almost every run and wreaking havoc inside the engine. He and Brandt had some lightweight wrist pins (and, reportedly, other go-fast goodies) built by Dick Landy, and they just didn’t hold up.

On eliminations Monday, despite reaching the semifinals, the engine never lived to the finish line. A 6.00 at only 186 mph beat Dale Pulde in round one, and a 5.77 at just 218 mph got him past McEwen, but he lost in the semifinals (on a holeshot of all things), to Meyer, 5.94, 252.80 to a shutoff 5.90 at 210.

(Armstrong remembers Prudhomme coming into his trailer and asking to borrow some of their wrist pins, which also were a special make – suggested by Ed Donovan – of Maraging 300 alloy. “After he blew up engines, he came storming into our trailer and asked me for some of our wrist pins,” said Armstrong. “I was in a bad mood anyway – trying to tune two cars [his and Wemett’s] – and I told him to get the f*** out of the trailer and that if he wanted our wrist pins, he had to ask Kenny. Kenny finally told me to give him some.” Prudhomme remembered it well; “I’d have told him the same thing if he came into my pit looking for parts after running two-tenths quicker than me,” he said with a laugh.)

In retrospect, Prudhomme’s performance became legendary, but it could have been even more so. “We didn’t have enough fuel on the other end, and we didn’t have computers on the car then to know what it really needed,” Prudhomme explained. “We just didn’t have enough to make it to the lights. At half-track, it was a missile, but it never made it to the lights under full power.”

The mind reels as to what might have happened had the engine lived.

“That’s my nitrous story; I hate to say, it’s not much of a story,” Prudhomme joked. “Pretty disappointing, right?”

Prudhomme's 5.63 stood as the best Funny Car run in class history for more than a year, until Rick Johnson piloted Roland Leong's wind-tunnel-tested Hawaiian Punch Dodge to a screaming 5.58 at 262.62 mph (also the fastest pass in history) at the 1985 Winternationals.

Not Kenny Bernstein

|

Before Indy 1982, Anderson and Wemett had never even run in the 5.8s, let alone dreamed about running in the 5.7s, but Bernstein’s misfortune became their fortune.

Bernstein and new crew chief Armstrong had struggled early in their first year together – later attributed to Bernstein prematurely shifting the two-speed transmission – and they embarrassingly had failed to qualify their Budweiser King Mercury LN-7 for the inaugural Big Bud Shootout in Indy. Ever the shrewd businessman, Bernstein approached Wemett and asked about the possibility of running the Bud King colors on his lookalike body, as he was qualified for the Shootout. The body was painted at the shop of Mike Kase, whose Speed Racer flopper both Armstrong and Anderson coincidentally had driven.

“We both were sponsored by Mercury LN-7, and we both were also sponsored by Motorcraft and Autolite, which made life easier; we did not have an oil or spark-plug conflict, plus identical bodies,” remembered Wemett. “We got our car painted for a one-race deal together, and we ran the old Speed Racer body in Brainerd not to hurt the LN-7 for Indy."

Armstrong says that he gave Wemett an entire Bud King engine to run in the car; Wemett remembers it as just the fuel system (pump and injector), but regardless, the result was lightning in a bottle, but not from a nitrous bottle.

“We knew our setup was improving, and with a couple things from Dale, up popped the 5.79,” said Wemett. “It was a great feeling to skip the .80s completely and to be No. 1 at Indy for even a small amount of time.”

(Armstrong admits that they had been “playing with” nitrous on the Budweiser King, but not as a direct performance adder. He explained, “At the time, most of the fuel at idle was going through the blower, and you had no control over where the fuel was going as it went through this big mixer into the manifold – the port nozzles weren’t active at idle – and the back pipes would get all wet, shooting raw fuel, and we were having a lot of trouble with dropped cylinders. If a cylinder was cold at the hit, it wasn’t going to fire when you hit the throttle, and we had pretty weak magnetos at the time. So I rigged up a nitrous system with eight nozzles in the manifold that we could adjust to get all eight pipes the same at idle; we’d run it at night at our shop in Brea [Calif.] so we could see the flames dancing about 2 inches out of the pipes. The goal was to have all eight cylinders at the same temperature when it got to the line to lessen the chance of a dropped cylinder. I had a pressure regulator set at 25 pounds for the nitrous; when Kenny floored it and the manifold pressure got up around 30 pounds, that shut off the nitrous flow. We didn’t use it as a power augmenter during the run.”)

Tom Anderson was runner-up to Bernstein in the same car the next year in Indy.

|

The Shootout was a major disappointment for Anderson and Wemett because their car broke a brake caliper while Anderson was trying to stop the car after the burnout in round one alongside Dale Pulde, and Monday wasn’t much better. After beating John Lombardo in round one with a 6.08, Anderson fell to eventual runner-up Gary Burgin and his Orange Baron Mustang in the second round.

Ironically, 1982 Indy "teammates" Bernstein and Anderson would meet in the final round the following year in Indy, and Bernstein, who had not only qualified that year for the Shootout but won it as well, came back to win Monday's Big Go, doubling up for a big weekend payday by defeating Anderson, 5.93 to a tire-shaking 6.04.

“We should have won the race,” lamented Anderson. “I was heartbroken.”

|

If fans were shocked by the performance of Anderson and Wemett, they were in no way ready for the show put on by Veney in Indy. Although he was clearly one of the dominant drivers in the Pro Comp ranks in the 1970s and early 1980s, running nitro is a whole other animal, but Veney approached the task as he did most things in life: methodically and meticulously.

Veney purchased a partially completed chassis from Tony Casarez and finished it himself (“He was very good but too slow”) and filled the framerails with a reliable and efficient engine that befit his budget, and it was that choice that led to his great performances.

Like Prudhomme, Veney was running a vane-style airplane pump – one used to transfer fuel between the wing tanks of a B-29 for stability – but was running just 87 percent nitro at a time when typical usage was in the middle 90s. Veney’s philosophy was clear and hard to argue with: Make it live to the other end.

He overcame the low nitro percentage with volume, running about 150 percent more fuel through his engine than his peers, and favored a roller cam over the traditional flat-tappet variety, a carryover from his potent alcohol powerplants. (“Like I told Keith Black: Flat tappets are for the tow truck.”) The cylinder heads – of his own design and manufacture – also were from his alcohol experience, with only the addition of stainless-steel exhaust valves.

“The whole idea was to keep the spark plug on it so it could run the whole track, which is why I ran the low percentage,” he said. “The engine was so efficient, and I was able to put so much air into it that I could run less percentage but more total volume and get the same amount of nitro burned as everyone else without the parts damage. I didn’t even have a spare engine, just pistons, rods, and sleeves.”

Needless to say, Veney also was not running the sometimes-volatile nitrous.

|

In just his fourth time out with the car on nitro, Veney followed his 5.84, 250.69 qualifier with a dazzling 5.78, 251.39 to beat Beadle in round one and a shocking 5.73 at 254.23 against Al Segrini in round two to set the national record. Inexperience and tire smoke lost the semifinals to Burgin.

“We were learning as we went and just kept getting after it,” he explained. “I knew it would go fast because the engine and all of the parts were in such good shape at the finish line. I had no idea it would go 254, but I knew it would go fast.

“In the semifinals, my inexperience bit us,” he admitted. “I got up there, and I could tell something was not right with the clutch – too much clearance or whatever it was -- because it was taking too much throttle to move the car. In an alcohol car, you could get a little run at the clutch by hitting the throttle, but that doesn’t work in a fuel car. I tried to drive it like an alcohol car by bringing the engine up against the brake to put a little load on the clutch, but it just blew the tires off.”

(Another little-known story involved drama and a quick fix on the Trans Am body that was buckling at speed during qualifying. NHRA insisted that he fix it or be disqualified from the event, so Veney fiberglassed a broomstick from fender to fender under the hood and fiberglassed some folded cardboard paper-towel tubes into the sides of the body for added rigidity. He’s nothing if not innovative.)

“We had a lot of fun, and I got the chance to run fuel while it was still cheap enough to do it,” he said. “My wife didn’t want me to do it; we used to go to Lions [Drag Strip, in the 1960s and 1970s] and see those guys get all burned up in the fuel Funny Cars. If I spent our money to race, that was OK – 'Get it out of your system' – but when I got my first Alcohol Funny Car, she told me, ‘Do anything you want, but I don’t want you ever driving a fuel Funny Car.’

“Oh well.”

|

So who, if anyone, was using nitrous that year in Indy?

Well, Meyer, for one. His system injected just the gas individually into each cylinder at the manifold at the hit of the throttle, as it had been since early spring.

Like Prudhomme and Veney, he had a high-volume vane-type fuel pump – his from Sid Waterman – which, in concert with some of Dick Maskin’s new cast-aluminum Dart cylinder heads and the nitrous usage, all came together for the monster performances in E-town and Indy.

“I’m reluctant to say all of the performance came from the nitrous,” he said. “The heads were definitely a big part of it, too. For me, the greater benefit of running nitrous was that it really helped us with parts attrition, taking away things like detonation and piston damage at the top end, and letting the engine live to the finish line.” I find it interesting that his explanation mirrors Veney’s “Make it live” philosophy, only from a different angle.

“The best thing about using nitrous was that it was injecting cold air – well below freezing – into the engine, which controlled the detonation; it’s amazing what these cars will do when they’re not detonating at the other end. And, obviously, it was condensed air, which let us put more fuel into the engine, too.

“I used a regulator on the nitrous system to tune the car at different tracks. At Denver, we’d just bump up the nitrous level to keep our consistency. We didn’t have to restrip the blowers often; we’d just bump the nitrous up because that always made it seem like you had a fresh blower on it. It was an easy tuning tool. We ran 251 at Norwalk the week before Englishtown, not even trying very hard, so I wasn’t surprised when it went 254 at Englishtown.”

Billy Meyer scored his first and only Indy win, defeating Gary Burgin in the final.

|

Meyer entered the U.S. Nationals on a high, just a few days after the birth of his first child, Benjamin (better known now by his middle name, Adam). After qualifying third with the 5.81 at 252 and a first-round loss in the Shootout, he powered past Jim Dunn and Bernstein Monday with runs of 5.88 and 5.84, beat Prudhomme on the 5.94 to 5.90 holeshot, then took an easy 5.91 victory over Burgin's tractionless Mustang.

Thanks to his Texas pal Richard Tharp, who was on the phone in the top-end tower, Meyer’s wife, Deborah, got to hear the final called live over the PA.

Meyer’s victory and Frank Hawley’s first-round loss gave Meyer the points lead, but that was the last of the good news. Hawley was runner-up at the Golden Gate Nationals to retake the lead, then held on for the title when both lost in the semifinals of the World Finals. More bad news followed. Meyer ran nitrous the rest of the year – it also was on Meyer’s Tripp Shumake-driven EXP that won that year’s World Finals at Orange County Int’l Raceway and in use when Meyer closed the year with a big win at OCIR's U.S. Manufacturers Funny Car Championships (on the 10-year anniversary of his first big win at the event in 1972) – but its use was banned for 1983.

In an editorial in National DRAGSTER after the U.S. Nationals, Wally Parks complained about the amount of parts attrition at the event – Top Fuel round one was an oildown mess – and hinted that something needed to be done to tame the power. Rightly or wrongly, nitrous was taking the blame.

“No one else had really figured out how to run it, and they were blowing up a lot of stuff,” said Meyer. “It wasn’t because I was brilliant; it was more dumb luck that we’d figured it out, but, to me, the thinking [behind banning its use] was backwards; I saw it as a way to cut parts attrition if used correctly.”

According to Meyer, NHRA polled Funny Car teams, and only two people voted for its retention: Meyer and Austin Coil, the latter of whom, according to Meyer, realized the parts-saving aspect of it. Regardless, Meyer was left in a bad spot after it was banned.

“When they banned it, it took us a year to recover,” he admitted. “It was a tuning crutch for me, and it got taken away. When you’re able to always give yourself ‘good air,’ you get complacent, and I was really a year behind on cams and heads and blowers. We were lost; I struggled as much as I’d ever struggled. We weren’t even competitive. Finally, [the Minor team] came to Waco [Texas] and put a motor in my car to give me a starting point and get me out of my funk.”

|

|

Meyer’s comments about Coil piqued my curiosity enough that I decided I should try to track down the now-nomadic and carefree Coil, who was kind enough to momentarily turn his back on a scenic ocean vista in northern Oregon, where he’s enjoying his regular summer retreat from SoCal’s heat wave, to answer my questions.

And, as it turns out, Coil’s Hawley-driven Chi-Town Hustler, winner of the Shootout that year, also was running nitrous, hence his support for its continuing legality. Mike Thermos from NOS had told Coil about Meyer’s success and urged Coil to try it.

Like Meyer, Coil used nitrous in a gaseous form and injected it into the engine, but unlike Meyer’s system, which was activated by him planting his heavy right foot on the loud pedal, the Chi-Town’s unit was activated by Hawley via a steering-wheel-mounted switch and, despite being active for the entire run, used just about an eighth of a pound per run. The system’s primary use was to help atomize the nitromethane to avoid dropping cylinders.

(Coil also was not fooled by Prudhomme’s fuel-pump-plumbed hoax and starting-line hoax – “Positively ridiculous” was his assertion about the implausible notion of plumbing aerated nitrous directly into the pump – but he said that at least one team [who shall remain nameless because I’m not able to confirm it] did fall for the ruse and quickly devised a similar unit at the event, which quickly caused the pump to cavitate and fail.)

"Ya know, you didn't have me fooled for a second, 'Snake.' "

|

Coil ran the system the rest of the year, won the championship, fruitlessly voted for its continued use, and, after a few small stumbles with dropped cylinders early the next year without the laughing gas, was able to “tune my way out of that” and went on to win the championship again. “I’d have been happier if they left us alone, but it wasn’t crippling,” he noted.

For all of their theories about how well nitrous – and many of their systems, for that matter – worked, the always verbally colorful Coil was quick to point out, “In that era, before computers [data recorders], none of us knew that [heck] worked; we were just throwing [stuff] out there and seeing what stuck against the wall. If things went OK, you’d come home and make up the theory that you wanted to believe in.

“Today, I’d bet that even the best of the people out there – including myself – really only understand about three-quarters of what’s going on in these cars. In the early 1980s, if we truly understood 20 percent of what was going on, we were lucky. Looking back, we didn’t know jack[stuff] about what the cars were doing. Since we got computers, we’re real certain that what we can see from standing on the starting line is almost always wrong.”

|

Naturally, while I had him on the line, I asked Coil if a racing comeback of any kind was on the horizon, and, to summarize his reply, if I were holding a Magic 8 Ball in my hand, the answer would be “Outlook not so good.”

He doesn’t miss the drama or the headaches of The Big Show, hasn’t found the right fit (despite many offers) in nostalgia racing, and misses being able to invent.

“If there was anything I was ever good at, I was good at creating something that no one else had that gave us an edge to win,” he said. “As the rules have gotten so all-encompassing, you’re not allowed to do that. So we all stand there with a barrel full of clutch discs that we know we can’t know exactly how they’re going to act, and we’re going to have to play Russian roulette with ‘Do we put another nut on it or not?’ and the other guy’s guess is going to be as good as mine. That just doesn’t seem like any fun. Fortunately, I had a very competent investment broker who guided me well throughout all the great years, and I’m not particularly worried about starving to death.”

OK, so that's the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth about nitrous use at the 1982 U.S. Nationals. For now. Is there a possibility that someone else was using nitrous that year? Absolutely. The good thing is there's always another column just a few days away. Thanks for reading.