Engineering the Train

|

In American, history, few images are more evocative, romantic, or nostalgic than that of a train rumbling down steel tracks, smoke billowing from its stack. The legendary Iron Horse, as much as the six-shooter, helped tame the Wild West, bringing people and goods across the nation.

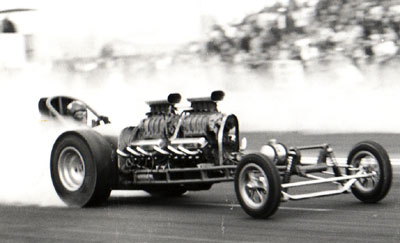

In the annals of drag racing history, few cars evoke those same nostalgic feelings as our own legendary train, the dual-engine Freight Train Top Gas dragster of John Peters and Nye Frank, which for three decades rumbled down our nation’s quarter-mile tracks, smoke billowing from its rear tires.

Born in a try-anything era where more was better and too much was just right, the Freight Train obtained legendary status not only for its string of record-breaking achievements but for the showmanship of its stewards, which ranged from its train-engineer-themed crew outfits (if they weren’t the first full-team crew outfits, they certainly were the most publicized) to the train horn mounted on the tow vehicle that sounded whenever the Train roared.

With Peters and Frank as engineers and a legendary roll call of conductors behind the wheel, including numerous drivers who wanted just to say they’d driven the legendary machine, the Train first departed the station in 1959 on its whistle-stop roll into history.

|

|

|

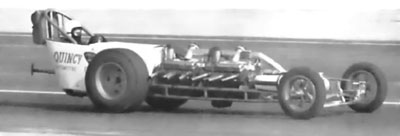

The car was always twin-engined but ran in a variety of configurations before it settled on its best-known appearance, with superchargers topping both Chevy engines. In fact, the first Train (which actually didn’t get its famous moniker until a few years later), sponsored by Quincy Automotive of Santa Monica, Calif., wasn’t even initially supercharged on its early voyages. The 100-inch-wheelbase car sported two injected 283 Chevys with a half-inch stroke and .060 overbore, and performance, while good, did not meet Peters’ expectations.

“ 'Lefty' Mudersbach had the record at that time at like 166, and the best we ran was 164,” Peters remembered. “We decided that wasn’t enough, so we added a front-mount 6-71 blower driving off the front of the crankshaft on the front engine. I took our crank over to Donovan and cut the front snout off, put a different snout on it, and machined it for a Halibrand quick-change gear. I made a couple of plates with bearings in them that mounted one on the blower and one on the front of the engine and overdrove the blower that way. The first ductwork we built was plenum that came off the side of the blower into a three-inch aluminum tube that would feed boost into the blower manifold on each engine.”

That setup was quickly modified, leaving the crank-driven blower to feed the front engine while a 6-71 blower was mounted atop the back engine, and a few weeks later, they finally put the blowers up on top of the front engine as well, which is the combination with which they won the 1963 Winternationals and the configuration that remained throughout its competition life.

|

|

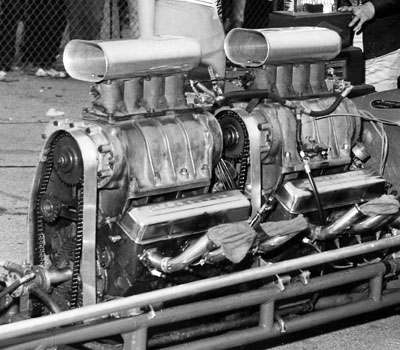

Eagle-eyed reader Bill Carrell was the first to spot it in the photo of the Train in the Pomona winner’s circle in the entry I posted last week, but the Pomona-winning machine's blowers were driven by chains, not belts. Here’s a blowup of that same pic. It was actually Carrell’s note to me, and the beginning of my research on the subject, that led to this article and my lengthy interview earlier this week with Peters.

“We only ran the chains for a short period of time,” explained Peters. “We were trying to keep the engines as close together as possible and as far back as possible to get the right weight percentages on the rear end. We only ran it that way for a few weeks because the chain would only last two or three runs and then they'd break. The chains were so long, and I don’t think we were using as large a chain as we should have; I think we were using a number 40 chain, and we should have been using like a 50. In Pomona, we changed them every couple of runs just to be safe.”

Bob Muravez was the driver then, and his Pomona win came on the heels of a big win at the 1962 March Meet that earned him a severe reprimand from his father and a demand that he stop racing if he hoped to be part of the family business. Peters was listed as the winner at the Winternationals (and initially as the driver when the car became the first Top Gasser to exceed 180 mph later that year), and Muravez’s roommate, Rex Slinker, was photographed holding the trophy standing next to a “who-me?” Muravez, who later -- as previously reported in this column and to be further explored in the near future – adopted the pseudonym Floyd Lippencott Jr. to avoid his father’s wrath.

|

|

Remembered Peters, “Bob quit for a while and I hired Bill Alexander to drive, but he said the car scared the hell out of him – this is when it had Monroe shocks on the front and it would rise up and pull one way or the other, so Bob came back. Rex Slinker, who just passed away a couple of years ago, was our stand-in driver whenever the media came to take pictures for articles. That went on for three or four months before they came up with the Floyd Lippencott deal.”

Almost coincidental to Muravez’s new alias, the Freight Train received its famous name. Years before, Tommy Ivo had dubbed the then-all-white car The Great White Steamship, but the Freight Train name came from Drag News columnist Judy Thompson, the first wife of Mickey Thompson, and her description of a notable performance at Fontana in 1963. Muravez remembered, "The car freewheeled that weekend, which caused the engine to detonate, and Judy remarked that it sounded like a freight train, and that name stuck, too."

The name game did little to stop Peters’ continued experimentation, and, as the car gained fame, he tried everything at his disposal to keep the car ahead of the pack, most of which came from his fertile imagination. “Everything we did back then was on us; you couldn’t really buy anything because there wasn’t really anything on the market,” he recalled.

|

|

|

|

As the car went faster and the wheelbase was lengthened (the final version of the Freight Train, which was built in 1968 at Frank Huszar’s Race Car Specialities shop, rode on a 209-inch wheelbase), Peters kept experimenting with better ways to drive the twin huffers.

“We moved the front engine forward and lengthened the car a little bit and machined the bottom blower drive hub on the back motor so that I could bolt a plate sprocket to it so we could get a double chain around it,” he remembered. “After that, I tried running one three-inch belt off the front engine and stuffed the front motor back as far as I could against the back motor and made a little intermediate shaft with a double-roll chain coupler that drove the rear blower out of the rear of the front blower, but that kept wanting to twist the drive impeller (on the left side of the blower) to the point it would get galled up with the other impeller. I tried making a torsion-bar shaft that went all the way through the impeller instead of the stub shafts that were pinned on each end; I undercut it in the middle and heat-treated it, but that didn’t work out, either.”

Through this all, the Train kept a rollin’, all night long, right into the history books and into the hearts of drag racing fans across the country.

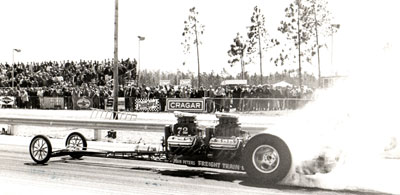

Roy “Goob” Tuller, who worked with Peters at Engel, took over as the driver in 1965 and racked up more milestones, including the first seven-second gas dragster clocking and a victory at the 1967 March Meet.

“Roy was the only guy I let take the car on tour by himself,” said Peters. “I flew back and forth to the major events, but he ran the match races by himself.”

Muravez was back in the car later in 1967 and scored again, at the Springnationals in Bristol, the same year that he piloted the Train to the first gas dragster passes of 190 and 200 mph. They won Lions’ big U.S. Pro Dragster race in 1967 and 1968 and pretty much set low e.t. for the class everywhere they went. Muravez added a third national event triumph, again at the Springnationals in 1969, which was held in Dallas. Sam Davis then wheeled the Train to victory in Bakersfield again, in 1970.

|

|

In 1970, shortly after the team began running a two-speed, Peters finally set aside his trademark Chevy powerplants when he teamed with veteran Walt Rhoades, who had two 354 early-model Chryslers – each displacing 428 inches. “We tried a lot of combinations over the years, but we got lucky, I guess, and had a lot of success,” said Peters, understating the obvious.

With Rhoades at the wheel, they ran a number of 7.0s and powered the Freight Train to its final major win at the 1971 Gatornationals.

“We ran a ton of seven-flats, at places like Gainesville; Indy; Houma, La.; Orange County; Long Beach; all over the United States, but not quite a six,” said Peters.

Later that year, with Muravez back at the wheel, the Freight Train finally recorded the first six-second gas dragster pass.

Although Top Gas racers had switched to duals over the years to try to keep pace with the Freight Train, in 1972, citing diminishing car counts, NHRA dropped Top Gas eliminator, whose cars were absorbed into Competition eliminator. It was the end of the tracks for Peters, who refused to "bracket race" the Freight Train. All told, the Freight Train made more than 1,700 passes – more than 1,300 of them with Muravez at the controls -- in 24 states, including Hawaii, at the hands of 13 drivers.

“Craig Breedlove drove it a couple of times, but never in competition,” said Peters, who now lives in Lakeport, Calif. “Mickey Thompson drove the car at Fontana one night when Muravez was out of town. Bill Alexander drove it a couple of times. Billy 'the Kid' Scott drove it for a while, and even Tom McEwen made one pass in it one night at Long Beach. Gerry Glenn drove it a couple of nights, at Irwindale and at Long Beach. Bob Noice drove it the last night we ran a Combo eliminator, at Santa Maria. He had never driven the car before, and we won the race with top speed and low e.t.”

|

|

Not everyone had immediate success in the car, and it didn’t always stay “on rails” as planned.

“Sam Davis crashed in it his first run down Long Beach,” recalled Peters. “He got it sideways but wasn’t used to driving a car with an open-tube rear end and rolled it over, threw the front engine right out on the ground. The only other time we crashed the car was when we took the two Chevys out of it at Fontana one day and put in one of the blown fuel Chryslers out of Bob Brissette’s Bonneville roadster. There was a bump just before the lights, and he was sideways smoking the tires when he hit it, and he barrel-rolled it. Bob broke a tooth and some bones in his feet, as I recall.”

Peters never drove the car, nor had any inclination to do so. He lost two close racing friends and former high-school buddies, 1960 Nationals champ Leonard Harris and Mickey Brown, to racing accidents at Lions.

“I saw how easy it was to jump into something you didn’t belong in and get killed,” he remembers.

“Leonard and I had just gotten back from deer hunting in Utah the Wednesday night before the Saturday night that he got killed. He was racing us when it happened. He was driving for another guy trying to help him sort out his car, and the steering shaft broke about three-quarter-track and he went into the fence. That was such a tragic loss because I believe, out of all of the drivers since the beginning of time, he is probably the best driver that ever sat in the seat of a race car. I knew him from high school – he was on the gymnastics team and had won All-City and All-State – and he was a machine.

|

|

“He only made one run in the Freight Train, but he got in the car and never even bothered with an easy pass. Bob Brissette was driving for me then, and Leonard ran as quick and fast as Bob or anyone else had ever run in the car. He only made the one run. He was something else.”

Today, the famous Freight Train’s chassis no longer meets certifications for exhibition runs and thus is relegated to charity displays for old friends, such as Vic Edelbrock’s recent Revved up 4 Kidz event in April and, of course, NHRA’s fan-pleasing Cacklefests, but Peters is still giving rides to drivers eager to say that they even once sat behind the wheel of the famous machine.

“Don Enriquez did one for me in 2004, and I’m trying to let a few of guys who are still around do the Cacklefest,” he said. “We’re going to Bowling Green [Ky.] for the National Hot Rod Reunion on Father’s Day weekend and stopping in Tulsa [Okla.] to pick up Roy [Tuller] and let him back in it."

Not that Peters wouldn’t love to make a modern-day Freight Train.

“If I could afford it, I’d like to build a new car with all of the up-to-date stuff,” he said, no doubt with the same dreamy-eyed look he used to get back in the day. “I think everyone would be surprised how fast it could run with a two-speed with some aluminum blocks and heads and some screw-type blowers. With the tires today and the racetracks groomed like they are, it could probably run 6.50s at 220 mph. Now wouldn’t that be something to see?”