'The Big Bang'

|

Imagine if a photo of a cataclysmic event taken 36 years ago instantly brought your name to people’s lips. Imagine if, despite your other accomplishments in life and racing, this one moment frozen in time on film became your legacy. Then you’ll know what it’s like to be Larry Brown.

A couple of weeks ago in this column, we laid out the five favorite images of drag racing photo ace Steve Reyes, and among them was Brown’s incident, an almost indecipherable moment when a massive explosion wrenched the engine from Brown’s dragster as he entered the lights in Tulsa, Okla., in 1972. We’ve heard Reyes’ side of the story, as seen through his camera lens, now it’s time to get the story of what happened from the man who lived it.

I contacted Brown after being copied on some e-mail messages between him and fellow Oklahoma Top Fuel hero Marvin Graham after the passing of fellow Okie Bobby Hightower. One thing led to another, and I asked Larry to share his tale of that fateful day in Tulsa. He was more than happy to oblige. Here's his story.

|

“I was born in 1940. I tell you this not to bore you but so that you will understand the chronological history of my drag racing past. My first experience at ‘big time’ drag racing came in 1958 at the U.S. Nationals in Oklahoma City. A friend and I soon built a B/Altered roadster and ran it locally around Oklahoma, but I really wanted to drive a dragster. By the early to mid-‘60s, I had partnered with Chester Garris (who was later Marvin Graham’s crew chief) to build a Jr. Fuel dragster that I would drive. The lightweight Jr. Fuel cars were a handful. I used to say that I could never see down the track due to tire smoke the first half and engine oil/blowby the second half. But this would be good training for things to come. This was during the period that Jr. Fuel cars, including ours, were winning Top Fuel races due largely to the Top Fuel cars having traction woes. I drove our car for two seasons with much success, but the allure of Top Fuel was too much for me, and I began to get offers to drive. The tires were coming around at that time, and the Top Fuel cars were far more competitive than the Juniors.

“By the late ‘60s, I had been hired on a winnings-percentage basis to drive a succession of AA/Fuel Dragsters, which was exactly where I had always wanted to be. One of my first rides was the full-bodied Jim Davis Taboo car, which gave Nat Quick his early start in paint design. Next came driving stints for the Dallas-based Chaos Kids, Boyd’s Auto Machine, J.L. Payne’s Busch & Payne’s AA/FD, Tony Casarez, and Robert Anderson. I won numerous races and twice won the Southwest Top Fuel Circuit championship.

“In the spring of 1971, I was offered the ride in Bob Dumont’s new rear-engine dragster. I readily accepted this new ride as it was the first rear-engine car in the area, patterned after [Don] Garlits’ success. The car was built by Mike Stewart of M&S Race Cars and was extremely light, high gear only, and featured a cast-iron 392 with a 3/8 stroker crank. We were very successful immediately; the car was performing well, and driving was fun again: no oil, no fires, no huge blowups, or so I thought. The car was so successful that we decided to enter it in Garlits' PRA Race in Tulsa in 1972. The race would be made up of a 32-car field, and the winner would receive a whopping $64,000! This was an unheard-of payoff at the time, but we liked our chances. This brings us to the real reason you are still reading this article: The Big Bang.

"It was only approximately 100 miles up the turnpike from Oklahoma City to Tulsa for the PRA race. Upon arrival, we soon discovered that we were among almost every one of the top cars at that time. In 1972, there was a mix of front- and rear-engine dragsters, the most common being front-engine, so our car was in the minority. When we rolled the car out of the trailer, we had a fresh 392 engine built by Dumont at his shop in Oklahoma City. The crew was Bill Coleman, Stewart, and Dumont. We went immediately to the starting line to walk the track and discovered that it was so sticky in its preparation that if your shoes weren’t laced tightly, it would pull them from your feet. I tell you this because given these circumstances and the large payout, I’m reasonably sure that most, or all, competitors had engines on kill.

|

|

|

|

“We ended three qualifying sessions with each run better than the previous but still not where we wanted to be in the field. As we prepared for our fourth and final qualifying effort, Dumont had a long conversation with Leroy Goldstein. Leroy told Bob that he was standing about midtrack and it sounded to him that the clutch had pulled the engine down (long before onboard data). Bobby pulled counterweight from the clutch and added blower speed. [Our next run] netted us the No. 12 spot and being in the top half of the field; that was to be our final attempt. I remember on the fifth and last session of qualifying, there was no one in the lanes – everyone had either blown up all their parts, given up, or were satisfied with their position. It was reported that there were well over 65 cars for a 32-car field. TOUGH!

“We were to run Gary Cochran first round. When we were in staging, Gary told me that I’d better be ready because he was, and to prove it, he showed me that he had on two firesuits, one over the other! As I said, everyone was serious. And he did, after all, drive a front-engine car. I, on the other hand, wore a prototype full-face helmet with an oversized shield and opening that my friend, Bill Simpson, had sent me. I also had the lightest firesuit that Simpson made, much like the suit the NASCAR drivers wear now. My shoes were Simpsons, made for road racers. I felt that I was immune to oildowns, fires, or injury from flying parts. All this just goes to show how much you don’t know. We won the first round and didn’t appear to hurt anything. When we got back to our pit area, there was a gathering of people, photogs and sponsor types that we weren’t used to. Now we had a 1 in 16 chance of winning the race. Not that great, but not that bad, either. The Pennzoil people were there as was Hays clutch, and Goodyear came rolling in the newest and best tires for us to use. With all the help, the car was soon ready to face Dennis Baca in the second round. I’m sure we added a few extra horses between rounds.

“After staging, Baca and I left together (no reaction timers in those days). The car pulled hard, carrying the front wheels somewhere about 100 feet before settling down for a very good run … I thought. At 1,000 feet, I hadn’t seen Baca yet and thought, ‘This is going good,’ but that was about to change.

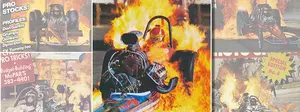

“Somewhere before the first light, there was a distinct tremble without much, if any, change in sound. The car never did lay over. The tremble became a shake as I reached for the chute release knowing something was definitely wrong. As the lever went down, it was as if it was the detonator on a bomb. All hell broke loose as there was a terrible shudder and a loud BANG! Not at all like a concussion; it was more like a breakage of metal. Then everything went black as the engine passed me by! It put 12 quarts of hot 60-weight Pennzoil and associated engine parts on me. There went my no fires, no oil, and no-broken-parts-hitting-me theory.

“When I finally got my oiled-down visor up, which was hard to do against the force of the air rushing by me, all I could see was smoke ahead – no parts. Good enough, I thought. The car, with the brakes on and the chutes out, didn’t go far at all. Less engine, clutch, and bellhousing, it probably didn’t weigh more than 600 pounds and I around 135. Before I came to a complete stop, I had released the belts and was pushing myself up on the roll cage. Once stopped, I held my opaque visor and stared into the framerails. Where the 1,000-pound engine had been there was only an aluminum oil pan and several pieces of crankshaft and main bearings. It was the most surreal feeling imaginable.

“Dumont and crew were on the scene almost immediately. I was still staring into the empty frame like a zombie, transfixed on what was not there any longer. I heard a crewmember exclaim as he exited the truck, ‘Where’s the engine?’ Someone else said, ‘It blew up!’ Dumont was heard to say, ‘The damn thing didn’t just vaporize, it has to be here somewhere!’

“In the confusion of medical personnel, track officials, and, by this time, spectators, it was about five minutes before I heard the report that they had recovered the bulk of the engine some 300 feet down and to the right of the track. Chester Garris had gone with the wrecker to retrieve it (Chet was always quick to help). After much deliberating on the method, the chassis and tire remains were returned to the pits. I was with the medical people because I had slight oil burns on my neck. I probably should have worn a heavier firesuit. Upon my return, the pit area was complete chaos. It seemed like everyone in Oklahoma was there. When the Goodyear engineers came to reclaim their well-used wheels and tires, I asked them about road-hazard warranty on them. We enjoyed a much-needed laugh together. As we struggled to load baskets of broken parts, we found that we were to run Warren & Coburn in the semifinals. Obviously, we were not going to show.

“Many manufacturers' reps came by the pits to tell Dumont to call and they would do anything possible to help us rebuild. They were very helpful and much appreciated. If I thought the hour after the explosion was a whirlwind, the next week was even more so. My phone rang off the hook, and one call was from Larry Bowers. Our Okie buddy Lee Owens worked for him, so they called to make fun of us, little knowing that in a few short weeks they would have an explosion almost exactly like ours! Poetic justice prevailed. Friends like Kenny Bernstein and Raymond Beadle called to gripe that they had worked for publicity for years and had never achieved what I had gotten in one run!

“The pictures you’ve seen of The Big Bang over the past 35 years or so were, at the time, in almost every newspaper across the nation, including the front page of the L.A. Times, and in almost all of the automotive magazines. It was also featured in the movie Funny Car Summer released in the mid-1970s. The latest pictorial offering was in Steve Reyes’ hard-cover book, Quarter Mile Chaos. Maybe all of this publicity made this run live on in drag racing history arguably as long as any other. The final verdict was that a broken crankshaft was the culprit.

|

“For years after this incident, Dennis Baca and I had a running conversation that I had ruined his car’s paint job, to which I always replied that if he hadn’t been behind, nothing would have happened to his paint job.

“Bob Dumont and I raced for two more seasons with some success. Bobby’s business had grown by leaps and bounds and required more and more of his time. Bob decided it was time to retire from active drag racing and concentrate on his business. I certainly missed his capabilities in my later career without him.

In the late 1970s, I started my own Funny Car operation and found how frightening it could be to be on my own for the first time in my career. With much help and advice from people such as George and Tom Hoover, Gordon Mineo, Billy Meyer, and Gene Snow, I became somewhat successful on a regional basis. I ran Funny Cars for the next few years, fielding a Plymouth Satellite, Arrow, Trans Am, and Corvette. My final race was in 1983. I seem to be known better for other accomplishments locally and regionally, but I guess if I only had the incident to call ‘fame,’ I would gladly take it over none.

“In retrospect, I know that I wouldn’t change anything about my career, including the experience told here, because I made so many lifelong friends, and I wouldn’t trade places with anyone in the world.”

Where are they now? Dumont owns Dumont’s Porsche Service, the premier Porsche service center in the Oklahoma area. Coleman owns and runs a fishing-guide service on Lake Texoma in southern Oklahoma. Stewart has a successful business buying and selling machinery in the Oklahoma City area. And Brown? He owned and operated a successful Mercedes repair shop in Oklahoma City but is now retired and “attempting not to fall off the adrenaline wagon.”

|  |

P.S. (Happy birthday, Mom!)