The road to Pomona

The 2019 season kicks off next Friday in Pomona, launching the NHRA season as it has every year since 1961. The Los Angeles County fairgrounds, known today as Fairplex, has become hallowed ground for NHRA race fans over the long and cherished history of the event, which at 59 years is the second longest in NHRA history behind the U.S. Nationals.

But how did NHRA end up planting its flag in this suburban wonderland?

NHRA’s Southern California roots certainly played a big role in decision and while there were a number of popular Southern California strips running NHRA meets at the time, few of them had the space availability that Pomona offered, and its weekly program, run by the Pomona Valley Timing Association, was very popular and, under the direction of the late Chuck Griffiths, had built a great infrastructure under the watchful eyes of NHRA.

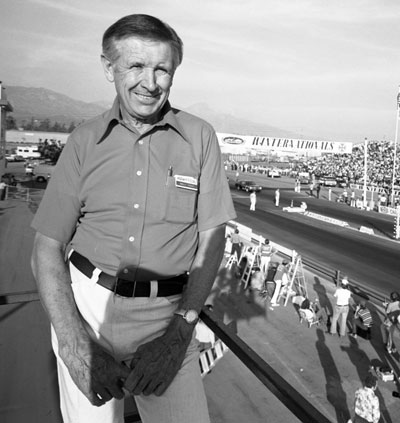

Pomona had been NHRA’s great success story in its earliest years. NHRA founder and President Wally Parks and team had spent the first two years of NHRA (1951 and ’52) working tirelessly with police officials across the country, asking for their help and cooperation in turning the public opinion about hot rodders. The real breakthrough and model of this desired cooperation had come in Pomona, when Police Chief Ralph Parker, who in December 1951 had written a hot rodding-favorable article in the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, which is distributed to law-enforcement groups throughout the United States, tasked motorcycle officer Bud Coons to begin interacting with the local car club, the Choppers. Coons got a first-hand look and understanding of the kind of people the sport attracted. Parker was honored in 1969, when Parks and the NHRA christened the Pomona Raceway track as "Parker Avenue."

“We had several friends who were killed in street racing accidents, and our club was real serious about getting everyone off the streets,” Griffith, who was then the president of the Choppers, told us a few years ago. “When I first met Chief Parker, he was a regular motorcycle officer in the late 1940s, and he knew who the racers were and was giving them a lot of tickets. Parker found out about our club meetings, and he began sending another Bud Coons as an emissary to our meetings.”

In a savvy move to further legitimize themselves in the eyes of civic officials, the Choppers rebranded themselves as the Pomona Valley Timing Association, and began using a timing system developed by Otto Crocker, who had also worked with Parks during his time with the dry lakes-based Southern California Timing Association. All of it helped reinforce the idea that the car club was serious about its hot rodding.

Before long, got the Choppers a chance to run at the airstrip in nearby Fontana, but the area was prone to high winds, and Parker was able to broker a deal with the Fairgrounds to pave an asphalt strip, eight-tenths of a mile long and 70 feet wide, down the western side of the Fairgrounds. The city paid for the paving out of its own pocket, with the agreement that the Choppers would repay the city out of the net profits realized by the operation of the strip. By season's end in 1952, nearly 200 entries jammed the Pomona strip each weekend. In 1953, NHRA staged its first official event, the Southern California Championship Drags, April 11-12, a joint venture of the NHRA and the PVTA in cooperation with the San Diego Timing Association and several local car clubs. The spectator turnout was phenomenal and far surpassed anything the organizers could have wished in their wildest dreams.

Clearly, there was an appetite for organized championship drag racing in Southern California, and the Pomona track provided it for years, competing alongside (and against) other SoCal favorites like Lions Dragstrip and San Fernando Raceway with a full slate of classes. Trophies were given to the eliminator winners and war bonds to the Top Eliminator winner. PVTA worked with Fairgrounds team, who assisted them with painters and electricians to keep the place running smoothly, and the PVTA helped keep up their end by keeping the car clubs in line. “We had to answer to Chief Parker, the Pomona City Council, the Fairgrounds, and, of course, the city of La Verne, which had a lot of local churches in the area,” said Griffith. “We did whatever we could do to make them like us, not hate us, and for the most part, it worked out real well.”

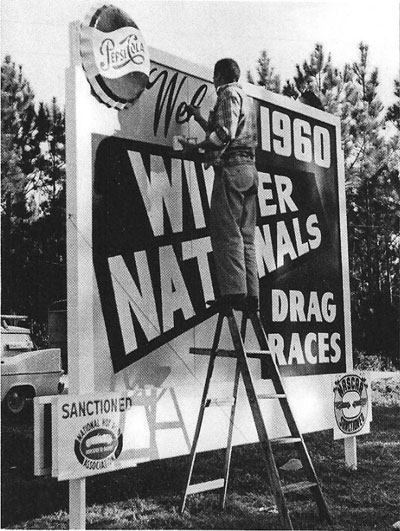

Fast forward to 1960, where NHRA racing had grown to the point of crowning national champions at an event that became known simply as “the Nationals” (and would not become known as the U.S. Nationals until 1972). In 1960, it was the only “national” event on the calendar and had hopscotched around the Midwest, from Great Bend, Kan. (1955) to Kansas City, Mo, (1956) to Oklahoma City (1957-58) and then to Detroit (1959-60) and was preparing for its move to Indy in 1961.

Diehard fans and old-timers, however, might well remember that before there was a Pomona Winternationals there was an NHRA-produced Winter Nationals (two words) in Daytona Beach, Fla., held during NASCAR’s fabled Speed Weeks competition. The primary goal for Parks was not to have it recognized as part of the NHRA series, but to provide an organized drag race that would draw local street racers away from Daytona on Speedweek nights. With national media attention focused on the event, the last thing that PR-conscious Parks needed was anyone giving hot rodding a very public black eye.

Although the Daytona event (which I’ll cover in a future column) had a big turnout, it was not financially successful (Parks said that they barely covered the cost of the trophies that were handed out), but Parks still saw the opportunity it could provide, especially closer to NHRA’s home base, which at the time was on Vermont Street in Los Angeles.

“NHRA's leaders saw the need for a major drag racing event west of the Rocky Mountains,” Parks said. “NHRA selected Pomona Raceway, where much of drag racing's rules and policies had been developed. From day one, it was a natural. Closely following the annual Tournament of Roses Parade in nearby Pasadena, the Winternationals was generally assured of good weather.”

“Wally always had a real fondness for Pomona,” recalled Griffith. “It’s like you always remember your first car. Pomona was Wally’s first dragstrip, and no matter how much more modern the other ones became, Pomona was always Wally’s favorite. He had a meeting with us and we decided to put it together. It was unbelievable what Wally could do. He was my mentor, and I believed in anything he said. NHRA had the biggest responsibilities in sponsoring and promoting the race. We just had to put up a strip ready for the race."

Griffith recalled that it didn’t take much persuasion by NHRA to convince local officials of the many benefits of staging the Winternationals. “Wally presented it to them in terms of dollars and cents, citing how many people would be coming in from out of town and how much they would be spending for food and lodging. And, of course, it would further our original goal of getting the kids off the streets. There really wasn’t much resistance.”

There was some concern that the event, held during the “Fuel Ban” years that precluded use of nitromethane at NHRA tracks, would impact the attendance in the face of a number of non-NHRA tracks in the region who still burned nitro, but those fears proved unfounded. Even though there were no cash awards -– the winners of Top, Middle, Little, and Street eliminators got Ford 390-cid high-performance engines presented by Ford and prize in Stock eliminator prize was a certificate for a color TV -– the racers turned out in numbers. Amazing weather and the strong support of local legends like Tom McEwen and Jack Chrisman primed the pump for a successful event.

In typical “Mongoose” braggadocio, McEwen proclaimed, "It was really a big deal when we heard the announcement [of the event]. People in Southern California were starving for a big championship race and now we had one. I'm sure that some of the fuel racers thought it would flop if they weren't there, but if I was present, you had everybody."

The successful event not only boosted NHRA’s local reputation but also put guys like Chrisman, who beat McEwen for Top Eliminator honors, Mickey Thompson, who won Middle Eliminator, and “Dyno Don” Nicholson, who won Stock, on the national radar.

"I remember coming back down the return road in front of all those people in the stands after I had won the final,” Nicholson said. “Everybody cheered and whistled from one end to the other. I was making about $100 a week then, and after the Pomona win, we got a call from back east to run a match race for $600. That was the start of my match racing career."

Nearly six decades later, we’re still here, still reaping the rewards of the hard work and beliefs of guys Parks, Parker, Coons, Griffith, PVTA board member and announcer Stan Adams (who would also later serve as track manager), and countless others who helped make Pomona a mecca for drag racing fans.

Phil Burgess can reached at pburgess@nhra.com