How much Jake can you take?

|

You know me, I’m always thrilled when a story is not only well-received, but also elicits responses that allow a follow-up, and that has certainly been the case after last week’s column on 1970s Funny Car driver Jake Johnston. Not only was he very appreciative of the column, but many of you also let it be known that you had no problem remembering him and hold his career in high esteem.

Wrote Richard Pederson, “Perhaps with the attention brought by the story, he may realize that he was/is rather revered, with his legendary status only fueled by his absence, and maybe show up, say, at the Bakersfield Hot Rod Reunion sometime. There's just enough missing to warrant a short follow-up piece maybe next week!”

Your wish is my command, Richard, but the question is, how much Jake can you take?

Some of the email I got demanded answers and brought not only me, but also Jake, to the realization that there was more to tell, leading to a couple of additional long and fun phone calls to try to expand on some things.

One of the topics that always comes up when I talk to the guys who lived that early 1970s match race circuit is the sheer number of dates they would run and all that went with it, and Johnston surely had his share of tales.

“At the peak of the season, in the summer, we’d run three or four times a week,” he remembered. “It was just me and one crewman, Ronnie Guyman. Ronnie passed away a few years back. It was just the two of us, and we busted our asses. Sometimes we’d travel 500 miles between back-to-back races. Back then, we didn’t have to take the engines apart after every run like they do today; we’d tear them down after every other race, maybe every six runs. I was easy on equipment.

When Jake Johnston was on the match race trail, it was just a two-man show, him and crewmember Ronnie Guyman, who's shown in this photo from New England Dragway submitted by Insider reader Gregory Safchuk.

|

“Racing was good to me,” he asserted. “I was young and got to travel the country and see almost every state in the union. It was a storybook kind of life. We worked hard and raced hard. Match racing was really our meat and potatoes; we enjoyed the prestige of going to a national event, but for me, they became just another race to win. No matter where or who I raced, I always wanted to win, and I was fortunate to win most of the races I was in. I wasn’t there to roll over and just collect the appearance money.”

Johnston got a percentage of what the car brought in, between 30 and 40 percent as he recalls. Gene Snow paid all of the running expenses on a budget that was just short of six figures despite running close to 100 dates a year. A typical deal for a popular car like his was $900 to $1,200 for three runs, guaranteed no matter his result.

Another subject that always comes up when talking about those days is the variety of tracks that the teams were booked into. One week you could be running at palatial and well-lit Orange County Int’l Raceway and the next at one of those tracks that my old pal Bret Kepner likes to jokingly refer to as a “big four” track: short, dark, narrow, and slippery.

“You never knew what to expect when you got booked into a new track,” Johnston agreed. “I remember running a track in Virginia one time. I checked it all out in the daylight, but we were scheduled to run at night. It was a narrow track, but it looked OK, but when we pulled up to run at night, they were lighting the track with searchlights and people’s cars parked along the track. There was plenty of light going down there, but when I got to the lights, the track dropped off, and suddenly there were no lights. It was like being in a closet. It was pitch black, and I had no idea where the end of the track was, let alone where I was.”

|

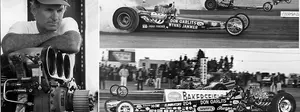

I came across the photo at right of Johnston racing Tommy Ivo’s Top Fueler in 1972 at Maple Grove Raceway, one of only two times that he remembers being paired against a dragster (the other was against Art Malone). According to the caption information on the back of the picture snapped by longtime track photographer Jim Cutler, Ivo broke the two-speed on the run, and Johnston won with a 6.86 at just 199 mph.

“Those kind of races didn’t mean a lot to me,” Johnston said. “When I raced, I wanted to run against equivalent cars."

The Insider’s ol’ pal, Cliff Morgan, wrote, “The year he ran that 6.72 at OCIR in the Blue Max, that made a huge impression on me. I was at that race and had come out early to watch qualifying. Gary Cochran was there in his front-motored Top Fuel car, a 392 Chrysler, and ran 6.72 on a test run. When Johnston ran that 6.72 later that night, I was astonished that he'd run as quick as Cochran's dragster.

“I am also wondering if Jake Johnston was the driver for a race at Lions in December 1971. Bill Leavitt ran the Quickie Too Mustang, with a real 392 Chrysler whale motor. Leavitt ran 6.48, which was the quickest e.t. ever for a flopper, but one of Snow's cars ran 6.49 (with an Elephant motor). I'm wondering if Johnston was the driver at that race. Of course, Leavitt's 6.48 with a 392 motor was wild! That's why I loved Lions -- you could see low e.t. of the world there on occasion.”

|

Morgan’s memory, as usual, was pretty darned good but not perfect (hey, it was 40-plus years ago). Leavitt did indeed shock the troops with a 6.48 at the event, billed as the Lions Grand Finale, but it was Pat Foster in Barry Setzer’s mighty Vega who ran the 6.49.

Johnston was there driving for Snow and, as the photo at right attests, ran against Leavitt in the final. Foster had broken a rear end in the first round and made the 6.49 on a test pass between rounds. Leavitt ran 6.53 in round one to beat “the Tentmaker,” Omar Carrothers, a wild 6.51 in the second round to dispatch Gary Burgin, and an easy 7.99 after Ron O’Donnell and crew couldn’t get Don Cook’s Damn Yankee out of the pits due to a transmission problem. Johnston, meanwhile, had run 6.68 on a first-round bye, a soft 7.76 when Jim Dunn couldn’t return after pitching a rod in round one, and a stout 6.59 to beat Kelly Brown.

Johnston got the drop on Leavitt in the final and had the lead until half-track before he lost traction and watched Leavitt scream to the 6.48 and a new national record. Johnston still posted a respectable 6.97 at just 177 mph.

|

While perusing Johnston’s photo file, I came across this interesting image, which I also remembered seeing in Drag Racing USA in 1972. The photo, taken by then National Dragster Editor Bill Holland, shows the frantic attempts by crewmembers to remove the parachute from Johnston’s car after it accidentally came out on the starting line in the semifinals at the 1972 Winternationals. Johnston had already beaten Leroy Goldstein and Dunn when the bad thing happened.

According to Holland, the group got the chute detached from its mounting point, and Richard Tharp carried it forward to show it to Johnston. Back then, there were no in-car radios to alert a driver that an opponent was having trouble, so Johnston did the only thing he could: stage the car against Ed McCulloch and pray for a red-light (which never came). Johnston did not run the car -- as it would have probably led to a lengthy conversation with officials – not that he didn’t think he could.

“I could have run the car,” he insists. “Every time I made a run, I assumed the chute wasn’t going to come out, so I was always on the brakes right away, and we had good brakes.”

Another interesting question that led to another of those “I never knew that” moments was a query from reader Don Wright about which other cars Johnston had driven, citing (correctly) that the DragList website lists Johnston as possibly having driven both Don Schumacher’s trick Wonder Wagon Vega coupe and “Jungle Jim” Liberman’s ’76 Monza.

|

It’s another case of close, but no cigar, as it turns out. Johnston never drove for “Jungle,” but he did drive a Wonder Wagon Funny Car -- just not Schumacher’s memorable, swoopy, low-riding, aero-cheating Vega, but that car’s complete opposite, the boxy, ill-handling, crash-prone Vega panel wagons that launched the sponsorship before Schumacher got involved. As I’d always heard the story, promoters Don Rackemann and Bob Kachler signed a three-year pact with ITT Continental Baking for the Wonder Bread deal, and Kachler came up with the idea to run the Vega panel wagons to simulate bread-delivery vehicles. Glenn Way, the driver of the Groundshakers fuel altered, was tapped to drive one and Kelly Brown the other. Brown struggled with the first car before its planned debut at the 1972 Supernationals, and, until he got his Funny Car license, Way asked Johnston to drive his car at the 1973 Winternationals.

“They couldn’t get the cars to run,” Johnston remembered. “Aerodynamically, it was bad. The car was never going to work. The shape of the back was a real low-pressure area, and at midtrack, it would get up on the tires and start skating and then break the tires loose. We tried putting spoilers on the back and opening up the back window, but nothing worked.”

Although National Dragster does report they were there, I can’t find a record of either driver listed on the final Winternationals qualifying sheet, meaning they may have withdrawn from the event during its unmemorable three-week rain delay. Johnston says he and Rackemann couldn’t agree on the financial part of him driving the car, and he left the team. The whole arrangement eventually collapsed, and Schumacher salvaged the deal with his team but couldn’t make the panel wagon work either and ended up running a pair of Vega coupes driven by him and Raymond Beadle. I'm trying to get the whole story on this weird and misunderstood part of drag racing history, so look for that in the future.

Johnston also reported that he had one-event shots driving for Tom McEwen (1973 March Meet) and in Dunn’s car in 1976 or 1977 when, for some reason, car owner Joe Pisano couldn’t get their car ready, but he never drove for Liberman.

OK, gang, that's it for another fun week. Thanks again, as always, for your contributions and support. See ya next week.