The slingshot's last hurrah

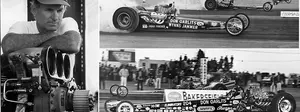

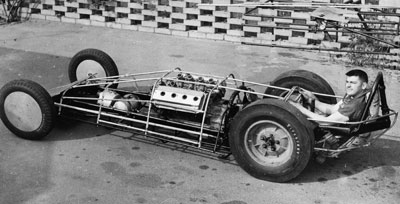

Who had the first slingshot dragster is certainly debateable, but Mickey Thompson long took credit for it with this car, pictured in 1954.

|

Tomorrow marks the anniversary of a very telling date in drag racing history, for it was Aug. 6, 1972 — 39 years ago — that the last front-engine Top Fueler was pushed into the winner’s circle at an NHRA national event. Art Marshall’s name was forever cemented into the NHRA history book when he drove his and Don Young’s dragster to victory at Le Grandnational outside of Montreal to claim the last major victory for a front-engine Top Fuel dragster.

The fabled slingshot dragster — a term coined by early adapter Leroy Neumeyer for the driver’s position, which hung out behind the rear axle “like a rock in a slingshot” — had been the dragster design of choice since the mid-1950s, when it was adopted by drivers like Mickey Thompson and Calvin Rice and became the iconic symbol of the sport to the masses; to some, it still is.

All of that began to change, of course, in 1971, when Don Garlits won the Winternationals with his rear-engine car, the genesis of which came following Garlits' horrific transmission explosion the year before that sawed off half of his right foot. As power had increased throughout the 1970s, slipper clutches were introduced to control the power, but they also generated massive heat, and despite improved bellhousings, clutch explosions began to claim lives at an alarming rate, so it made great sense to put all of that running gear behind the driver instead of at his feet.

Front-engine dragsters continued to held their own in 1971, with only Garlits (who also won the Springnationals) and, surprisingly, Arnie Behling (Summernationals) winning in rear-engine machines. Steve Carbone famously beat Garlits in the “burndown” Indy final with his slingshot, and Jimmy King, Pat Dakin, Gerry Glenn, and Hank Johnson all won in front-engine cars; Glenn’s win at the World Finals also made him the final front-engine world champ.

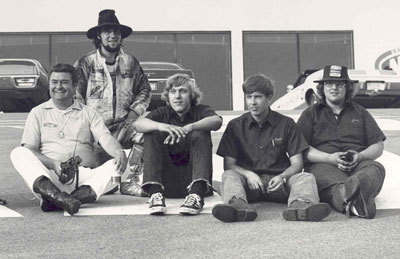

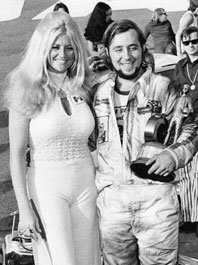

Chatting with Art Marshall, right, and car owner Brian Beattie in Gainesville.

|

The handwriting seemed to be on the wall, though, when Carl Olson (Pomona), Garlits (Gainesville), Chip Woodall (Columbus), and Jeb Allen (Englishtown) opened 1972 with rear-engine wins before Marshall momentarily turned the class on its head with his unexpected win at Sanair Int’l Dragstrip. Think David and Goliath with a slightly more powerful slingshot.

I met Marshall for the first time earlier this year in Gainesville, where he was driving Brian Beattie’s immaculately restored Jim & Allison Lee Great Expectations II front-engine Top Fueler in the Cacklefest. As soon as the motors went silent, I hopped the guardwall and introduced myself to him, and he seemed genuinely surprised yet very pleased that he still was remembered for his lone win. With this column in mind, I got his phone number and, after a little phone tag, we connected. I had all of my research lined up, but he asked for some time to gather his recollections and those of some of his old crew and promised to send me his memories via email, which, a few weeks later, he did and did wonderfully, supplying me with detail about the event beyond what I can find in the pages of National DRAGSTER’s coverage. I’ve saved them just for this week to honor the anniversary of the end of an era.

|

|

Former NHRA Chief Starter Buster Couch, left, with Marshall (rear) and his young team: Pete Keller, Don Young, and Jack Bashford.

|

Marshall’s journey to Top Fuel trivia question actually begins the year before when he buckled into his first Top Fuel entry, the unusual injected twin-engine big-block dragster shown at right that then was allowed by the rules. Although the car ran in the low 7.0s at more than 200 mph, Garlits had run as quick as 6.21, and the other fuel dragsters were well into the sixes as they had been since 1967.

Seeking a more conventional machine, Marshall and Young set their eyes on the so-called “slab-sided” front-engine Hot Wheels dragster of Don Prudhomme (not Tom McEwen’s similar car, as had been erroneously reported for years). Prudhomme already had made the switch to a rear-engine car in mid-1971 with his John Buttera-built wedge and subsequent Fuller-built lightweight “yellow feather.”

The duo headed west from their Springfield, N.J., home base in their old '64 Buick station wagon push car and purchased the car, along with an engine, trailer, spare shorty body, and spare third-member, for $5,700. (“It is true, I did go through Roland Leong’s garbage at Keith Black’s and found some usable spare pistons that came in handy in Canada,” admits Marshall.)

The team painted the once-white car black and campaigned it in 1972 with crewmembers Pete Keller and Jack Bashford, but even with a famous car in the possession, it still was a struggle for the sparsely funded team of eager young racers. Marshall himself was just 23.

“Our ‘shop’ was my parents’ single-car garage,” he remembered. “Because of a make-shift engine hoist, my mom would always know when we were pulling out the motor because her china closet on the other side of the garage wall would act like it was in a 7.0 earthquake. Since I worked at Van Iderstine’s Speed Centers, we had a small sponsorship for nitro and small parts.”

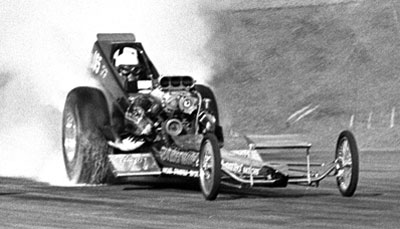

After an unspectacular early season, the team loaded its equipment to head north of the border for Le Grandnational, which was only in its second year, and its victory was certainly no walk in the Canadian park. After driving all night, the team arrived at Sanair Friday morning and did its normal maintenance in the car, but on its first qualifying pass, a 6.55 at 223.88 that eventually landed the team in the No. 7 spot in the eight-car field otherwise exclusively comprised of rear-engine cars, things went horribly wrong.

“Coming through the lights, I was in a ball of fire,” Marshall recalled. “We burned a few pistons very badly, and oil was pumping out of the headers feeding this inferno. I hit the fire bottle and went for the chutes. Immediately, the flames claimed the pilot chutes, and they burned right off. Once we got back to our pit, NHRA officials were there to look over the car and inspect my flamesuit. It wasn’t pretty; both the car and I were covered in oil.

|

“We loaded the car up and headed for the nearest handheld coin car wash. We stripped the car totally down, pressure washed the oil from everything, scraped most of what was left of the pistons off the cylinder walls, then loaded the car back up and drove around Montreal to try to borrow a cylinder hone. That was not as easy as it sounds because of our limited French, all of us being so young, and having little money, but we somehow got lucky and found someone willing to help. With an extension cord running from this little auto-repair shop, we honed the cylinders right in the trailer. Ready for assembly, we headed back to Sanair.”

The team spent the rest of Saturday rebuilding the car, and it wasn’t until around midnight that it was finally able to fire the engine to check everything. After a few hours of sleep, the tired crew headed back to the track Sunday morning.

“We just happened to be pitted next to Clayton Harris, who we were to run in the first round,” recalled Marshall. “He knew the engine was hurt badly and came over to us and said, ‘I hope you guys fixed it real good.’ I guess it was his way of playing with our minds. We knew that game, too, so before taking the car out of the trailer, Pete poured STP down the pipes of the hurt cylinders. Once the car was unloaded, we started it for the warm-up, and smoke began billowing out of the zoomies. Looking over at Clayton Harris’ pit, he was walking around, shaking his head with a smirk on his face. Hey, when you are running against the best in the business, you need every advantage you can think of.”

Marshall advanced to the final round on red-lights by Clayton Harris (above) in round one and Winternationals champ Carl Olson in the semifinals (below).

|

|

From that point on, things just went Marshall’s way. Harris, the No. 3 qualifier, and Olson, No. 6, both red-lighted to Marshall, setting up a final-round encounter with Allen, who was hot off his own history-making moment in Englishtown a few weeks earlier where, at age 18 years, 1 month, he became (and still rules as) the youngest Top Fuel winner in NHRA history.

(I’d be remiss in my telling of this tale if I didn’t acknowledge two things. First, a five-tenths Tree inexplicably was being used in Canada instead of the four-tenths Tree used in the other events that season. Second, there are some who think that Marshall and team may have extended their push-down and staging procedures in another bit of gamesmanship. The ND report says that Harris “had problems holding [the car] on the line,” causing it to “lurch” off the starting line, typically the result of an overheated clutch. Olson admitted to a similar experience on his foul, but, to avoid any sour-grape concerns, declined further public comment. You be the judge.)

“We had a lucky break or two, but were solidly there round after round, bringing our A game to the starting line every time,” said Marshall, whose 6.62 was right with Harris’ invalidated 6.60 but whose piston-eating 6.72 was outdistanced by Olson’s negated, early shutoff 6.65.

Allen, meanwhile, had raced from the No. 6 qualifying spot past Herm Petersen on a huge holeshot, 6.58 to 6.47, then beat Canada’s quickest fueler, the Ken McLean-driven, Gary Beck-tuned entry, again on a holeshot, 6.44 to 6.39, in the semifinals.

Marshall wrapped up his historic victory by defeating Summernationals champ Jeb Allen, near lane, who smoked the tires in water from his overheated engine.

|

With Allen holding a better than two-tenths performance advantage and Allen’s sharp starting-line reactions, it seemed like the teenage sensation from Bellflower, Calif., might win again.

In the final, Allen’s dragster went up in smoke when percolating water from a too-warm engine surged past the O-ring on the fill cap — this is back when the fuel engines ran water in the blocks and heads — and spilled beneath his rear tires. (Again, in the interest of fair reporting, Allen, like Olson, deferred from finger-pointing but remembered that Marshall’s car was just being pushed down the fire-up road as he was beginning his burnout.)

Marshall’s underdog victory was staggering and no doubt brought a smile to those die-hard fans and racers who still thought that the only place a fuel engine belonged was in front of the driver, and it certainly made for a career day for Marshall, Young, and team.

“The win paid $2,500 from NHRA and about $5,000 in contingencies — wow, making money drag racing!” joked Marshall, who also went on to win the Division 1 Top Fuel championship that season.

Marshall, with "trophies" in hand.

|

Marshall today: Still a slingshot driver.

|

“Naturally, it took a few years for anyone to recognize the significance,” said Marshall, who now lives in West Palm Beach, Fla., where he’s licensed to fly and repair helicopters and also works at former NHRA Sport Compact world champ Nelson Hoyos’ Driven2Win drag racing school. “Over the years, I was mostly a trivia question, but now with the nostalgia movement and the reunions, the interest in the front-engine cars is back."

Although front-engine Top Fuelers continued to race even into 1973, they never again reached the winner’s circle. The design once thought to be state-of-the-art and that had captured 35 Top Fuel wins was clearly inferior to its rear-engine counterpart in almost every way, and the handwriting was on the wall, this time in indelible ink.

Marshall’s car now resides at Don Garlits’ Museum of Drag Racing in Florida, where it rests in history, albeit restored to its original white Hot Wheels paint scheme.