This could get ugly

Drag racing machines have long been known as rolling pieces of art, with intricately designed paint schemes, pinstriping, gleaming chrome, and detail beyond what the outside world’s most obsessed might find acceptable, but (to borrow from the Constitution) when in the course of human events it becomes necessary to make that next round or next race, sometimes pretty doesn’t matter as much as having the car ready to run.

A few weeks ago, reader Jon Hoffman suggested a column built around photos of battle-scarred drag cars that nonetheless showed up for the next weekend’s wars. After a little ramp-up period, here’s what has come in through the mail and what I found in a quick scour through our file of scanned images. (I’m sure that I would find a lot more leafing through the thousands of folders full of prints, but that’s for another day. Maybe.)

|

This first photo comes to us from the driver himself, Vic Morse, who wheeled the Mister T Corvette in the late 1960s and early 1970s. If you’ve been following this column for a few years, you know that Corvettes were pretty cursed in their earliest outings (Exhibit A | Exhibit B), and Morse’s was no exception. This photo shows the Mister T 'Vette at Orange County Int’l Raceway 10 days after it flipped in Bakersfield in 1970.

“A rear heim end broke on a qualifying run and flipped the car,” he said. “I slid through at 189 mph and qualified, but the car was hurt pretty bad. It almost wore through the roll bar. I was unhurt and thankful. The chassis went back to [Dick] Fletcher, and the body was repaired in Garden Grove [Calif.]. All the crew guys were volunteers and did not sleep much. We even had one kid that worked at Jack in the Box. He would keep the hunger pangs away with burgers. I will never forget that bunch of guys. True grit.”

Today, Morse does sales for R.V. Morse Machine (“You Bring It, We’ll Bore It!”) in Orange, Calif., which specializes in high-flow throttle bodies.

These next photos were sent by David McGriff, who found them at various places across the printed and digital realms and had no photo credits, so if it’s yours, speak up, and I’ll credit it.

|

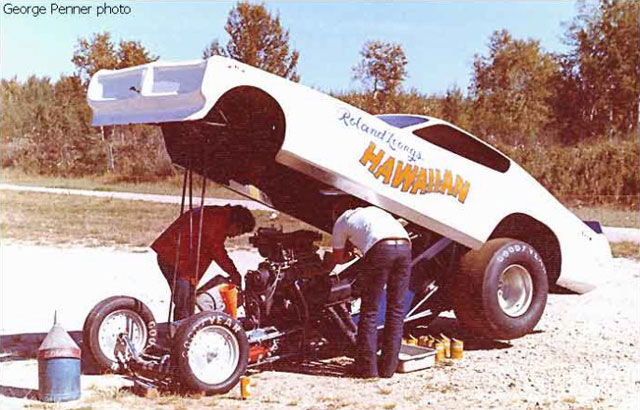

Roland Leong was a relentless match race campaigner in the 1970s, and the Hawaiian was always a popular draw for promoters and fans alike, so when a thief made off with Leong’s rig from a Gary, Ind., Holiday Inn parking lot in the summer of 1973, he bought this Buttera-built/Charger-bodied car from Ray Alley (driven by Kenny Bernstein) to continue barnstorming the country. The photo was taken at Bison Dragways in Winnipeg, Man., according to Allan Bedard. who pointed me to this link.

“I lost everything,” Leong told me. “All they found was an empty truck. At the time, I had a truck like [Dick] Landy's, an enclosed body truck. I lost all the tools, spare engine, transmission, rear ends, everything. I sold the truck, bought a duallie with a Chaparral trailer, and went back on the road. I was out of business for about two months.”

The late Leroy Chadderton had been the driver but parted company with Leong after the theft, and Leong brought in Gordie Bonin, who had just left the Hodgson & Jenner Pacemaker team, for the first of two stints with the Hawaiian. He was runner-up in his first match race in the car, then followed with a less spectacular outing in Detroit, where, as he recalled to me for a DRAGSTER article a few years ago, he "got crossed up, put it in the weeds on the sidelines, totaled the body, and spent the night in a Detroit emergency [room], but Ro still wanted me to finish the season." (Photo by George Penner)

|

The late 1970s War Eagle Trans Ams of Dale Pulde and partner Mike Hamby were among the prettiest cars to ever grace a dragstrip, but this wasn’t one of them. In fact, this one didn’t even belong to them. After finishing sixth on the NHRA circuit in 1977, the duo had a “humbling” 1978 season with a new car that gave them fits due to a different engine location. They sold that car and leased back their 1977 car with plans of having Steve Plueger duplicate the chassis for them for 1979. They ran the Winternationals in 1978 with this car – which obviously they did not paint but which also had some battle scars – but did not qualify. The for-sale sign on the front of the trailer also is interesting because Pomona was their last race with a trailer; they debuted their new 18-wheeler at the Gatornationals that year.

|

Mike Burkhart's 1973 Vega bore the wounds of a number of blower explosions in 1973 due to a fuel-system setup that was focused around quick delivery of nitro to the engine. On the 70sfunnycars.com site, driver David Ray reported, “When you hit the throttle, it sounded like a shotgun going off.” After three blower explosions in quick succession, Ray said he decided "the hell with repainting it, I'd better stock up on blowers and manifolds!"

|

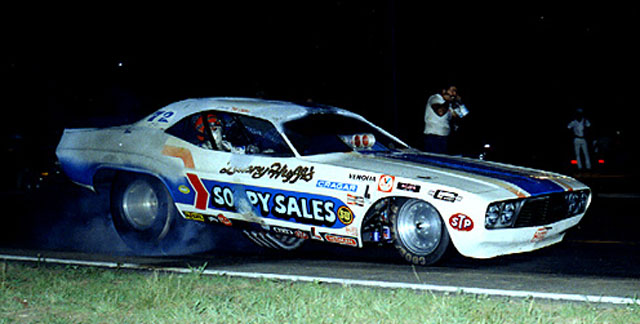

Larry Huff's Soapy Sales floppers also were nice-looking pieces, but this ’73-74 Challenger, wheeled by Dave Beebe, obviously had been through the wars. Damage to the right-rear quarterpanel is obvious, but I also think I see roof damage, meaning that the car could have been on its lid. Beebe drove this car to his only national event win, at the 1973 Springnationals in Columbus, where he defeated recent Gatornationals champ Pat Foster in the final. The Soapy Sales cars – which dated back to Top Fuelers in the late 1960s/early 1970s, promoted Huff’s laundry-detergent business. (In my research, I even stumbled upon an April 1970 issue of an Australian newspaper, The Age, that had a story about Huff and driver Steve Carbone going Down Under to race at Calder as he prepared to introduce his detergents in Australia.)

|

Certainly one of the leaders in the primered-car-from-hell hall of fame is Don Green’s Rat Trap Satellite ablaze at the 1973 March Meet with well-traveled Jim Adolph in the hot seat. I’m not sure whose photo this is – our own Leslie Lovett, Don Gillespie, and John Shanks all got shots of the Bakersfield barbecue – but you gotta love the shoe-polish lettering (including the oddly placed question mark after Rat Trap). Below is another unfinished Rat Trap -- looks like gel coat -- when Tom Ferraro drove the car. That also was 1973, but I'm not sure if it was before of after Adolph. Dennis Fowler, who went on to field the pretty Sundance cars, was a partner with Green on these cars. This image below is from the extensive collection of "Nitro Steve" Dull, who was kind enough to send it to me to replace the copyright-watermarked version that McGriff sent.

|

|

A few columns ago, I showed you a photo from the NHRA files of the final round of the 1972 Summernationals between Don Schumacher and Ed McCulloch, in which both bodies were covered in enough damaged spots to put a smile on Earl Scheib’s face. Above is another McCulloch body in transition. I’m guessing this might be 1976 (his ’74 car had the then-fashionable front-fender bubbles; this body does not), but you certainly have to admire the penmanship (um, shoe-polish-manship?) of whoever lettered the body. Shoe polish can be a tricky medium, but they did just fine and even included his nickname on the roofline.

Concluded McGriff, “I know there are a lot more of these primered beauties; in fact, there is even a picture of [Tommy] Ivo's Arrow in his book that had some body damage. I guess with today’s vinyl wraps and spare bodies, we aren't going to see this again, but it is always interesting to see how it was in the day. Who could forget the World Finals 'Frankenstein' of Shirl Greer way back when?”

McGriff’s point is valid; I can’t remember the last time a name team came to a national event looking as if it had just survived a zombie attack, but I’m sure it has happened. But with TV time at stake for the all-important sponsors, spare bodies, quickly accessible vinyl “paint jobs," and large and well-organized crews, it’s certainly very much a rarity.

|

To McGriff’s other point about Greer’s car ... well, who could forget? Certainly not me. I’d already pulled this beauty of a photo of Greer’s melted Mustang before I got McGriff’s message, and it’s clear that even though necessity was the mother of invention for this monstrosity, it sure was ugly.

It’s a tale well-told, of how Greer suffered a major fire during the final qualifying session at the 1974 World Finals while involved in a tight championship race with Paul Smith, who had the lead, just ahead of Greer, Don Prudhomme, and reigning world champ Frank Hall.

Greer suffered burns to his hands and face, and the entire rear section of the car was burned. “As they took me away on the stretcher, I looked at the car and said to myself that that was the end of that one, and there was no way I was gonna get enough points to win,” said Greer in a 1974 interview with National DRAGSTER.

But because Smith and Hall surprisingly failed to qualify, Greer would be in the points lead if he made it to the line for round one, so his pals wouldn’t let him quit. They hauled the remains to Steve Montrelli’s shop to work on the engine and running gear while Smith and his crew took dimensions for the back half of the car to chassis builder Don Long’s shop to begin building a replacement rear end out of aluminum. “We knew we didn’t have enough time to do it with fiberglass because there wasn’t enough time for it to set up, so we had to use aluminum,” recalled Smith. The newly formed rear end was attached to the remains of the body using “hundreds of rivets, screws, and rolls of duct tape,” recalled Bonin, who also was part of the thrash.

Greer checked himself out of the hospital, won the first round, and clinched the championship when Prudhomme – his lone remaining rival – was defeated by Pulde in round two.

|

And speaking of "Desperate men do desperate things,” there’s always the 1981 Winternationals and the “Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” where Raymond Beadle’s Blue Max lost its roof in a winning semifinal battle over Prudhomme, and pretty much the entire pit area helped transplant the roof off of fellow Texan Kenny Bernstein’s Budweiser King Arrow onto the Blue Max Horizon.

“Raymond and I were good friends and hung out a lot in those days, so it was just a normal thing for me to offer,” Bernstein told me a few years ago for a National DRAGSTER Readers Choice article I did on famous pit-area thrashes. ”When you get to a final, you have to do what you have to do. There wasn’t a question in anyone’s mind.”

They cut Bernstein's roof off at the bottom of the windshield pillars, then taped and pop-riveted it to the topless Max shell and added some fiberglass with a quick hardener agent and hoped for the best. They didn’t win the final against Billy Meyer (another Texan) but created an unforgettable moment in drag racing history.

|

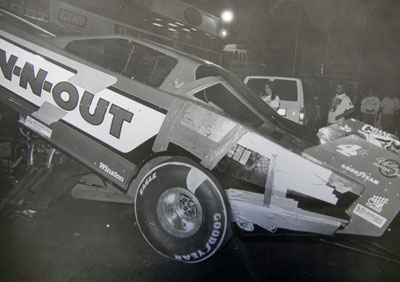

As famous as that moment is, it had a near-equal a decade later when Mark Oswald blew the left-rear tire in winning the semifinals of the 1991 Gatornationals in Jeff and Susan Bernstein’s In-N-Out Trans Am, taking with it the quarterpanel and portions of the roof and rear deck.

Incredibly, the other semifinal round had featured another body-destroying climax when Tom Hoover’s Scott Color Film Trans Am kaboomed the blower and body in the lights while losing to John Force. As the Bill Schultz-led Bernstein team and members of several other teams stood surveying the damage in their pit, a flatbed truck carrying the remains of Hoover's body trundled past, and, in what was a serendipitous coincidence, the left-rear quarterrpanel was one of that body’s most intact regions.

The group – including high-profile guys from other teams like McCulloch and Bernie Fedderly -- fell upon the corpse like vultures, hacking and sawing away the needed pieces, which were then taped, riveted, and added to the In-N-Out, car, with sheet metal covering the few gaps. Unlike in Pomona, the effort was successful, and Oswald defeated Force to win the final.

Sometimes, I guess, ugly can be functional and fast.