A bold yet frustrating attempt

As always seems to be the case with any mysteries raised in this column, the sleuths of the Insider Nation always solve the case. Today's story, about Bill Traylor's Bold Attempt streamliner that I featured here a few weeks ago, is just Exhibit No. 1,245 (roughly).

In hindsight, I'm a bit embarrassed that I didn’t put the pieces together sooner to remember this car in its later incarnation, but several others did. Although the car never made it big in Top Fuel, it did enjoy track time with the Zizzo family with alcohol in the tank. I heard from Traylor's son, Mark, as well as from Jerry Westhouse, who worked with the senior Traylor on the car, to get the story behind its build, and I reached out to current Top Fuel pilot T.J. Zizzo, one of our NHRA.com bloggers, to get his family's side of the story.

|

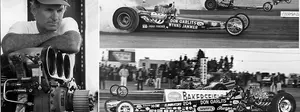

Before he built the Bold Attempt streamliner, Bill Traylor was an AHRA world record holder with his fuel coupe, named The Animal, built around a rare Al Williams aluminum tube chassis. He owned Traylor Engineering in Palatine, Ill., where he did automotive machine work and built dragster front wheels. One of his customers was Don Garlits, who purchased three or four sets a year, and the shop also was a popular summer stopover spot for the likes of Garlits, Don Cook, and Jim Nicoll.

"While my dad was not famous like some of the legends like Garlits, he was universally known and loved within the sport," said Mark. "He was always known to be out on the edge and willing to help anyone out at the track. Arnie Behling, Don Colosimo, Don Schumacher, Sid Seeley, Marvin Graham, and Marvin Schwartz are just a few of the guys that were regular faces at my dad's shop."

Traylor and Colosimo later partnered to run a front-engine Top Fuel dragster, the Chicago Missile, on the UDRA and IHRA circuits as well as on the match race circuit. Westhouse began working on the crew in 1970, and when Traylor and Colosimo broke up in 1972, Westhouse became Traylor's new partner.

The body for Traylor's fuel coupe had been built by Dave Stuckey, so it was Stuckey to whom Traylor turned for his first rear-engine dragster. Not content to simply follow the crowd to the back-motor side, the idea of a streamlined dragster was conceived.

|

From his Wichita, Kan., shop, Stuckey built the chassis with a 210-inch wheelbase and a standard aluminum body to go with it. They purchased a new aluminum 426 Milodon block -- serial No. 2 -- for the race engine and mated it to a Lenco two-speed with a 9-inch Ford rear end, though they also were one of first rear-engine dragster teams to experiment with a Crowerglide. Again fleeing from convention, Traylor decided to use a new Goodyear drag slick designed for the Funny Cars of the time.

The construction of the streamliner body led to an interesting story told by Mark. "Stuckey was really concerned about keeping the weight down. He knew how thick he wanted the paint to be but had no idea about calculating the surface area. He called several aerospace-engineer friends to come look at it to see if they could calculate an area for it. None of them had any idea how to get an accurate area. Dave had a ton of little 4-by-4-inch notepads around the house, so he took them to the shop and struck a line of symmetry down the center of the car and began taping sheets of paper to the body, cutting in slivers and wedges where it was required to follow the curvature of the body. When he was done, he counted up the number of sheets he used and calculated the area of the body and the volume of paint he needed to put the minimum amount of paint on the car. While I am clearly biased, I think this is by far the prettiest streamliner Top Fuel car ever produced."

|

|

Once the car was completed, Westhouse was chosen to drive the new ride, which was shaken down with conventional bodywork.

"We ran the dragster with the aluminum body in 1973 at UDRA races and some IHRA races," remembered Westhouse, who today works for Newman/Haas Racing. "Bill wanted to sort the car out before we ran the streamliner. It was an uphill battle with a new driver, new chassis, and a new engine combination. We ran good at a couple of races but were consistently fighting tire shake. If only we'd had data acquisition! The streamliner body was run once for a qualifying pass at the IHRA Spring Nationals in Bristol, and it shook the tires. The best pass we ran that year was a 6.55 at 230 mph.

"We ran the car a couple of times in 1974 without good results. At that time, Bill wanted someone else to drive, so we broke up in late 1974."

"Jerry was new to this level of race car, and my dad was not terribly happy with Jerry's performance in the car," Mark agreed. "I am not saying anything bad against Jerry, he is a good friend, but they were having a lot of tire-shake problems and were struggling getting the new combination running right. It was also my dad's first rear-engine car. "

The Bold Attempt was short-lived for a number of reasons, according to Mark. Primarily, his father had partnered with Tom Klausler and Bill O'Connor on a factory Lola Atlantic team with a Carl Haas association and was building Atlantic engines for Rahal, James King, and others as well as for Formula Ford, Can-Am, Formula B, and other road racing applications.

"One of his best friends said he had started being approached about putting together a deal to run at Indy, but it was probably a few years off in reality," noted Mark. "That additional focus of road racing being added in was probably the biggest reason for the project to slow down. I think my dad started seeing that the real growth for him in engine building lay in road racing more so than drag racing. At that time, there was more money flowing that way."

Traylor contracted Weber-Christian disease, a very rare condition, and the dragster was sold to defray medical costs. Traylor died April 12, 1976, at age 36. His son is trying to locate the original Animal fuel coupe, so if you've seen it or have any idea where it might be, drop me a line.

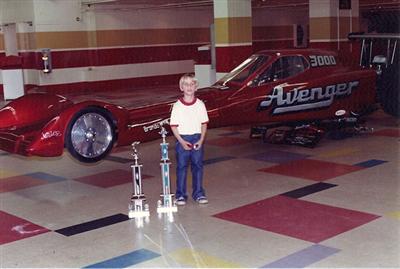

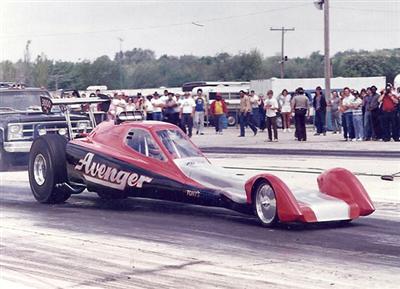

His father, Tony, had been partners with the late Al DaPozzo, and when he ventured out on his own, the Stuckey car was his first. It came with both bodies, but the chassis was too short, so it was lengthened to 265 inches, as was the streamliner body. Zizzo ran the car with the traditional aluminum body as a Top Alcohol Dragster from 1980 to 1982.

"My dad, being the wild and crazy guy that he is, decided to do burnouts inside the Rosemont Horizon on the clay tractor-pulling surface in front of a packed house with The Streamliner mounted on the chassis. He finally ran it at the dragstrip in 1982 with the injector under the body, but the engine starved for air, so in 1984, he ran it at Byron with the injector sticking out of the rear of the body. It was still starved for air. The body was too aerodynamic, and the air just went right over the injector, and the engine went rich downtrack. My dad said he could never get the car over 200 mph.

"The next step was to put an Eddie Hill-style scoop toward the windshield, but that never came to fruition. My dad built a new longer Alcohol Dragster chassis, and The Streamliner went in the rafters of the garage, where it sits today. My dad has high hopes -- after he is done campaigning our Top Fuel dragster -- to someday build a chassis and bring that streamliner to Bonneville. He is a licensed SCTA Bonneville driver and went 262 mph a year ago in an AA/Gas Lakester. My dad said The Streamliner was the coolest car to drive because it was so quiet, but it was way too heavy to be competitive. Now I know why my dad does not like to sell his old race cars. Someday, someone will want to know what happened to that old race car, and there it will be, up in the rafters of our race car shop."