The 1977 NHRA U.S. Nationals Yearbook

|

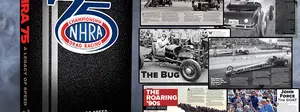

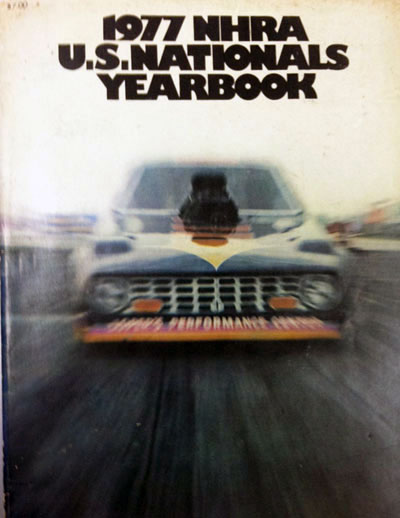

Drag racing fans still love the printed word (thank goodness for me!), which explains why a lot of us still have library-worthy collections of old drag racing magazines – Super Stock, Drag Racing USA, Drag News, Hot Rod, Popular Hot Rodding – sitting on our shelves. And for many hard-core fans, their collection might not be considered complete without the book pictured at right, the 1977 NHRA U.S. Nationals Yearbook.

I’ve been in this publishing business for more than a quarter-century, and it’s still, hands-down, the prettiest, most impactful drag racing book I’ve ever read. (Yes, better in some ways than anything I’ve ever been in charge of or involved with during my time here at NHRA, which I think is some pretty high praise.) The book, written by a virutal unknown in the field, captures the essence of Indy in beautifully descriptive words with great photos and a wonderful layout. If there were one book I wanted to give to someone to describe what Indy feels like, this would be it.

The sad truth is that for some reason, my collection does not include one of these wonderful books, and I hadn’t even seen a copy for years, but thanks to Insider reader Craig Hughes, I was able to enjoy it once again. Craig was interested in the story behind the book and asked if I’d ever done a column on the book or if I’d be interested in doing so and offered to lend me his copy. (Yes, he made sure he underlined the word “lend” in his email, and I don’t blame him. I'm going to apologize right now for the quality of the photos here, but there was just no way to scan the book on a flatbed scanner without risking damaging it.)

My old pal Todd Veney, with whom I collaborated on the writing of a series of NHRA season annuals for UMI Publications in the early 1990s, echoed my praise for it. "Phenomenal," he called it. "I've read it about 100 times." His copy comes courtesy of his famous dad, Ken, who recieved a copy of the book from the publisher. (Ken was runner-up in Pro Comp that year to Dale Armstrong.)

|

When Hughes' book arrived, I couldn’t wait to get at it. Cracking it open, it even smelled old, that musty smell that books get when they’re packed away, but I tore through its now-nostalgia-laced pages again in a couple of hours, marveling at not only the writing and the photography, but also at the completeness of the package even 34 years later.

The book not only tells the story of the event, from the early-arriving campers to the crowning of champs, but also has a great stats package that includes complete ladders for Top Fuel (32 cars!), Funny Car, Pro Stock, and Pro Comp (32 cars as well!) and a thick section with a headshot, car shot, short bio, and autograph for all 96 of the drivers who qualified for those fields (can you imagine how hard it must have been to get all of those 96 signatures?). There’s also a huge Sportsman class-winners section with car shots of ALL the class winners.

The writing is incredibly colorful and descriptive. No nuance is left untouched, from the preparations made by the teams to those made by the concession staff and along the Manufacturers Midway, along with knowing comments about how, day after day, the same routine is played out: the same drive to the track, the ever-more-familiar security guards and ticket takers. How clutch dust just never seems to come off your hands; how tires get heavier as the weekend wears on. (“They slip in one’s hands and fall against one’s chest, leaving their rings of black.”)

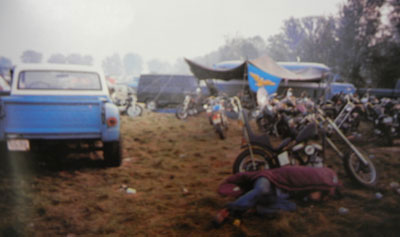

Early on, the author compares the scene to a medieval tournament, how the tents in the campground are like those in the fields of yore; the drivers become knights in their driving armor, their cars the steeds (the dragsters, it is pointed out, even have lance-like bodies). The pit area is their kingdom, the transporter the castle, its rear doors open like drawbridges. The announcer’s voice is the trumpet, calling them to battle.

|

|

Each day has its own chapter, and the results are reported, but not in newsy fashion. Larry Lombardo’s crash and fire in Bill Jenkins’ Monza and Ronnie Manchester’s loan of his car to the team and Dale Emery's wild nose-wheelie Funny Car crash are recounted in detail. The author clearly knew the cars, the engines, and the crews and was up on current news, such as Billy Meyer’s fire in Montreal just weeks earlier.

He captured the look, the feel, the smell of everything from the first rays of day, when the dirt areas of the pits are undisturbed and the grass wet with dew, to the trailer lights flickering on and the whir of the electric winch. Subtleties such as “tires and fuel tanks shielded from the burning sun” are noted, and astute observations are made even about fellow members of the media.

He describes the movement of the crowd as it tramples the grass and raises clouds of dust in the gravel; how kids race from trailer to trailer as they arrive but by mid-afternoon are sapped of energy by the sun and how their heads start to droop and weary wives just hope to survive the day.

Technical details about the cars and procedures are explained in everyday but colorful terms. Photos of the campgrounds and campers huddled in sleeping bags or simply passed out from too much partying share space with race photos, all of which are handsomely laid out through the pages.

After I was done marveling at the book and how it reminded me of things I forget about the event or take for granted, the detective work began. Now I, too, wanted to know the story behind the story.

Externally, the book carried only its title and the company name, Bold Horizon Enterprises. Google came up empty. But inside, tucked away in the back between the class-winners photos and the ladders, was a brief acknowledgements page listing those involved in the project and signed by John C. Plisky. There was a phone number in the credits, but, naturally, it was no longer in service, but it was connected to a city in New Jersey. A Google search combining those terms yielded a phone number and led to one of those “This may be the weirdest question you hear this week …” introductions and a series of good news-bad news moments.

John Plisky, a man with a dream

|

The good news is that I reached John Plisky. The bad news is that it wasn’t that John Plisky. The good news is that it was his son. The bad news is that his father passed away last year at age 71 from complications of pneumonia. The good news is that his son was involved in the publication and had great recall of the history of the yearbook. And there’s also one piece of amazing serendipity that I’ll save for the end of the column.

The “In retrospect” page in the book shared information about the team that the senior Plisky had assembled, which included professional photographers Jim Joern and Steve Phillips; the latter also served as the book’s graphic designer. Also on the team were New Jersey high school sophomore Peter Pasley and his older brother Richard and Plisky’s sons, John and Jimmy, whose “boundless enthusiasm” their dad credited.

What came to light after my interview with his son is that the publication was a grand dream, pushed forward in the face of impossible odds, cost, and logistics through sheer love of the sport and determination of heart.

“My dad grew up in Linden, N.J., and they used to run cars at the local airport there in the 1950s, and his dad would take him to the races, and he later began to take my brother, Jimmy, and I to the races in Englishtown in the early ‘70s, and we even drove out to the Supernationals in California in 1972,” explained Plisky.

“He knew that there was always an annual publication after each year’s Indy 500, and he wanted to do one for drag racing’s biggest event. He had very romantic notions about the whole idea, but he was very naïve. He had no experience in publishing or advertising or selling books and no cash-flow-management skills, but his enthusiasm was infectious. He just lit up when he talked about doing it, and that inspired the people to get involved.”

The senior Plisky was so committed to the project that he quit his job at an insurance agency and dug into the family savings to finance the book. “It was a huge, huge leap,” his son admitted.

The team pulled together throughout the Labor Day weekend, arriving early each day at the track and staying well past dark to capture the entire scene.

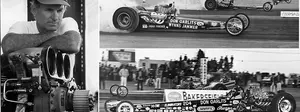

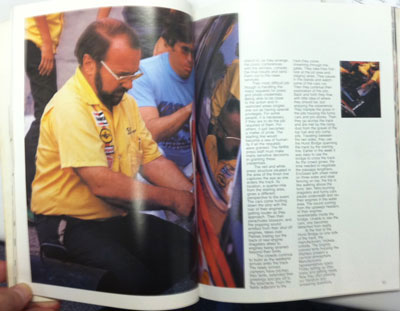

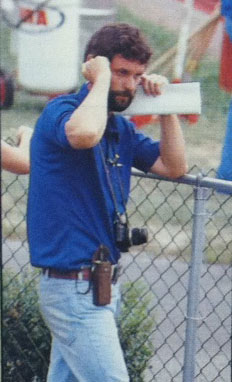

The junior Plisky, age 12 in Indy

|

“I was on the line shooting photos, but none of them made it in the book,” said the younger Plisky, who was 12 at the time (photo guidelines have since changed significantly). “I remember leaving every night half dead and covered in rubber specks and throwing away my T-shirt knowing that my mother was never going to wash it.

“My dad wasn’t a very accomplished photographer, and we shared an Olympus OM-2. He took the driver portraits for the back of the book; I got all of the autographs. The drivers had no idea what this was going to be, and it was more likely that a kid would get the autograph than an adult, but the drivers were very accommodating.”

And once the event ended, the work was just as daunting.

“I helped cull through hundreds of rolls and rolls of slide film to find the images for the book,” he recalled. “It was like, ‘OK, we need a headshot picture of Prudhomme,’ and I’d find them all, and we’d decide which one was best.”

His dad, whose only journalism experience came from a few articles he had written for Super Stock, did all of the writing, an impressive feat, and one that clearly came from the heart as much as the fingers.

“You can see his romantic notion of the event comparing it to knights in shining armor,” said his proud son. “That’s the way he looked at the whole process.”

As time-consuming and mentally draining as the writing must have been, bigger hurdles lay ahead.

“We didn’t have much of an ad budget; almost everything went into getting it created,” said Plisky. “He underestimated the cost and the cash flow of laying it all out upfront. I think he convinced the photo-separation people to do all of the separations before being paid. I remember going to the printer up in New Hampshire, trying to convince the guy to release the book so we could fill orders. It went something like, ‘Well, I don’t have the money now, but the ads are in National DRAGSTER next week …’ It was definitely an adventure.”

His son couldn’t remember exactly when the book was completed, but if you believe the flyleaf, it was 1978 by the time it hit the market, which only made selling the book that much harder.

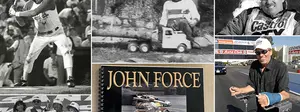

Plisky today, holding the yearbook and one of the ads for the book.

|

“Artistically, it blew everything away, but I’m not sure how many we sold. It wasn’t that successful at the time. I think the original print run was 10,000, but I know we didn’t sell anywhere near that many,” he admitted. “The problem was, it was a 1977 yearbook, and once it turned to 1978, there were some people who wanted to look back, but it became stale. There were other people who thought it was the event program and not a yearbook, so the sales tapered off pretty quickly. We drove out to the ‘78 Indy event and sold some. At the time, I think the official souvenir program sold for a buck, so it was a hard sell at $7. People who looked at it said they had to have it, but to get them to look at a $7 book wasn’t easy.”

But with a handsome finished product in his hands, the senior Plisky hoped it would impress NHRA officials to do one the following year as well.

“My dad thought that NHRA would be blown away by it because it was so much better than the program was at the time, and he’d done all of the thinking and put it all together, and that they might incorporate him into the fold and put him in charge of doing it,” he said. “He had meetings with Wally Parks and NHRA’s merchandising person at the time, but NHRA already pretty much had a procedure and people in place at the time for the program, and they didn’t believe anyone would spend $7 on a yearbook.”

Father and son shared an office through the end of his life, administering retirement plans for small companies; they talked occasionally about the book, and the senior Plisky died knowing that his book was much-appreciated in the end.

“It ended up costing him money – he went through a lot of his savings – but if he had the chance to do it every year, he would have been living his dream. He would have been over the moon. In the end, he knew that it was appreciated; it’s just too bad it wasn’t a business success.”

I couldn’t agree more, and I wish more people had the opportunity to see it. Plisky says he has considered making the book available again – everything from a DVD or CD-ROM containing just the raw pages up through on-demand publishing – to share his father’s work, but, like the original, there’s no way to gauge whether the expense would match the demand (I’d sure be interested to hear how much demand there is; you can email your name and address to j.plisky@verizon.net with "US Nationals Yearbook" in the subject line to be notified of any developments).

I’ll close this inspirational tale with the amazing tidbit I promised earlier in the article. Well, “amazing” perhaps is the wrong word, but “appropriate” seems, well, appropriate.

Although I got the email about the book from reader Hughes on June 21, I had been holding off work on the article so that I might present it around the time of this year’s Indy event. I interviewed Plisky on Tuesday and told him my plan was to publish it today, Aug. 26.

That’s when he told me that tomorrow will be the one-year anniversary of his father’s passing.

“What a great tribute to me dad,” he said.

Again, I couldn’t agree more.