Drag books, drag movies, drag nicknames, and heroes that we’ve lost

The Western Swing is history, and my bags are unpacked for a couple of weeks, allowing me to play a little catchup. A lot has happened since my last column three weeks ago, so here we go.

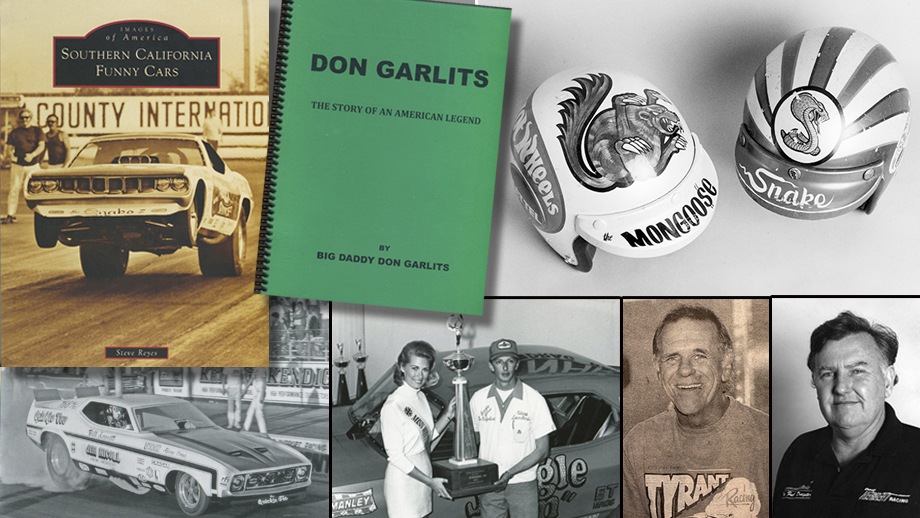

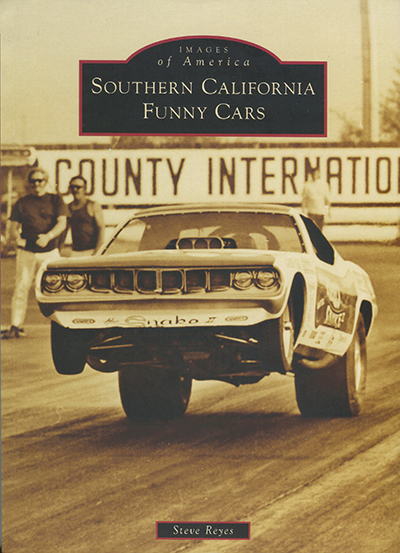

Steve Reyes’ newest drag racing history book arrived on my desk, and it’s one that I’ve been eagerly awaiting as the subject matter, Southern California Funny Cars, is near and dear to my heart. Before moving to Florida, Reyes crisscrossed the country, chronicling the great races of the 1970s, but his home was California. His first book, also published by the historical photo publishers at Arcadia Publishing, was Northern California Drag Racing, which covered places like Fremont Dragstrip, Bakersfield Raceway, Half Moon Bay, Sacramento, the Salinas Airfield, and more, and that I reviewed in this column.

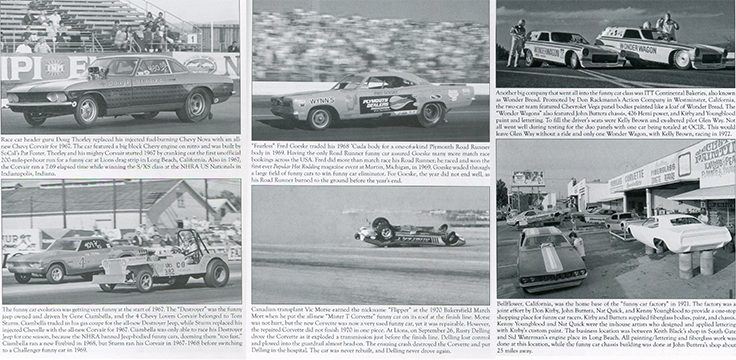

The topic of Reyes’ new book shifts to Southern California and covers the early Funny Car action at fabled tracks such as Lions Dragstrip, Irwindale Raceway, Orange County International Raceway, Pomona Raceway, Riverside Raceway, and more. Reyes offers a Funny Car history lesson and draws strong lines between the forerunners of what we know as Funny Cars like the Mooneyham & Sharp 554 nitro coupe, Bob Davis’ "Jolly Green Giant" Impala, the A/FXers of Dick Landy and others, and, of course, Jack Chrisman’s Comet.

From there, all of your SoCal favorites are here: Not just “the Snake” (what a brilliant cover photo!) and “the Mongoose,” but tons of others, from early pioneers like Roland Leong’s "Hawaiian,” “Fearless Fred” Goeske, “Big John” Mazmanian, Doug Thorley, the Pisano Bros., and Randy Walls, to the wild and wacky, like Junior Brogdon’s stretched-out "Phony Pony" Mustang, Sheldon Konblett’s wild "Snoopy" Jaguar, Warren Gunter’s "Durachrome Bug,” the topless (and ill-fated) Corvettes and Jeeps.

Into the ‘70s, we get the almost-uncontrollable rear-engined cars, “Big Jim” Dunn, Lil’ John Lombardo, the L.A. Hooker, the Barry Setzer Vega, Mickey Thompson, Braskett & Burgin, the “Trojan Horse,” and more that will ignite your memories.

Reyes has long been known for his Johnny-on-the-Spot crash photos, and with this lineup of wild machines, you can get your fill of moments gone wrong, as well as candid personality photos and behind-the-scenes images. The photos are accompanied by thick, insightful, and well-researched captions telling you much more about each car and driver. You can find the book for sale online here.

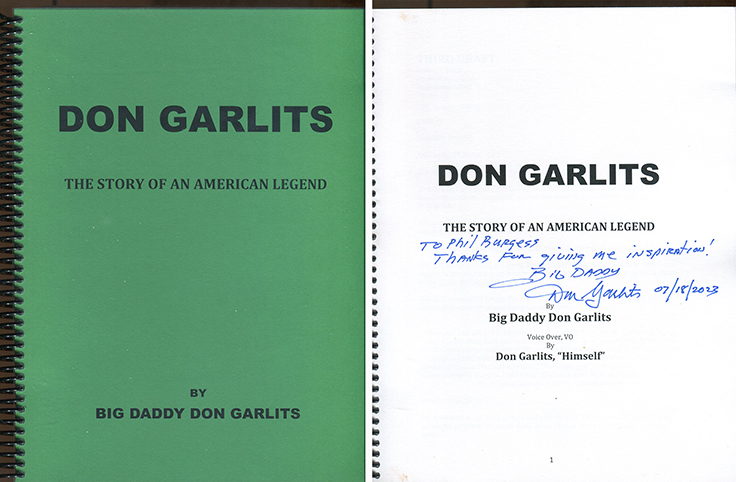

And speaking of great written works, I received in the mail from drag racing legend “Big Daddy” Don Garlits the final version of the screenplay (autographed even … how cool!) that he has written for an autobiographical movie project.

As originally outlined in our online scoop about the project a few weeks ago, Don Garlits, The Story of an American Legend, will chronicle the life of one of drag racing’s greatest heroes, from childhood through success and catastrophe.

Originally Garlits told me that he intended to only take the script up through his history 5.63 pass and world championship in 1975, but he got so into it that he ended up chronicling his entire career in a tidy 125 pages.

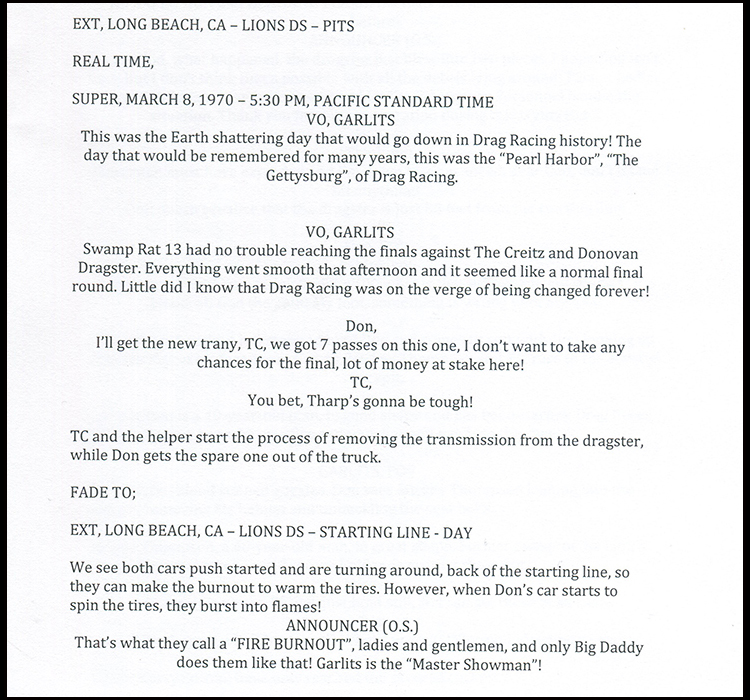

It’s all here, from the terrible fire in Chester, the horrific Lions transmission explosion, and both blowovers to the triumphs of championships and revolutionary car builds. Here's a quick page preceding the Lions incident:

Garlits puts us not only in the cars but inside his head, which is very cool because the world didn’t really get a lot of first-person quotes from those early incidents and successes. Even though Garlits' dialogue for the screenplay has the benefit of decades of hindsight, it’s still spellbinding to read how he remembers the incidents now.

The film ends with the electric dragster project and remembrances to the many who joined him on his journey but are now gone, including wife Pat, T.C. Lemons, Connie Swingle, Art Malone, brother Ed Garlits, and Bob Taaffee, all of whom are included in the screenplay in one fashion or another.

He’s not really sure what will become of his work, but he’s hoping for anything from a feature film (a la Heart Like A Wheel and Snake & Mongoose) to a streaming project that might find a home on Netflix or Prime Video or another popular network. He’s promised to keep me up to date on the developments, and I’ll let you know when he does.

So, I asked on Facebook, who should play “Big Daddy” in the movie? (I asked Garlits the same question, but he deferred, saying that would be up to the producers.)

He was portrayed in Heart Like A Wheel by Bill McKinney as a banana-chomping grizzled veteran in what I felt was a decent performance, including lifting Shirley Muldowney into the cockpit of his dragster and signing her license ("What the hell. Might as well get some of you gals out of the kitchen and into the stands.”) and then battling her throughout the decades.

Among the suggestions on Facebook were Robert Duvall, Dennis Quaid, Timothy Chalamet, Jude Law, Taron Egerton, Matthew Rhys, Scott Eastwood, and (just kidding, I hope) Jason Mamoa. If it is Duvall, they sure as hell better add a line to the script that says, “I love the smell of nitro in the morning.”

As I leafed through the Garlits screenplay, it struck me how his great nickname — coined by NHRA announcer Bernie Partridge at the 1962 NHRA U.S. Nationals with Don the young father to daughter Donna and Gay Lyn — has become an amazing calling card that never gets old.

Nicknames, obviously, were a huge deal in the 1960s and ‘70s and gave us other memorable nicknames like “the Snake” and “the Mongoose.” It’s always been my position (and surely not mine alone) that one should never give themselves a nickname — it has to be bestowed upon you. The Beatles certainly didn’t start calling themselves “The Fab Four.”

Partridge tagged Garlits and Prudhomme crewmember Joel Purcell gave his driver “the Snake” for his starting-line skills and lean physique. I forgive my late, great pal Tom McEwen for dubbing himself “the Mongoose” because, well, hell, promoting himself in whatever way he could was his jam and, of course, was his way of trying to one-up Prudhomme, with the mongoose being the animal quick enough to kill a snake. (And then you gotta love “the Zookeeper,” John Mulligan, who figured he could run herd over all of them or George Schreiber, who, as Mike Goyda reminded me, chose “The Bushmaster” as his nickname that name because the Bushmaster is the only snake that could whip a mongoose. (Much in the same vein was what “the Ace” Ed McCulloch did to “the King,” Jerry Ruth. (I also forgive Ruth for naming himself, because, hey ... have you ever met him?). Ditto for Connie Kalitta, for dubbing himself “the Bounty Hunter” and following through with a list of names on the car that he then defeated. A cook nickname and a visual connection? Priceless.

Using nicknames is great for us writers so that we can switch from using the term Garlits to “Big Daddy” and “Large Father” instead of repeating his last name; ditto for Prudhomme and “the Snake" and “the Vipe.”

Or sometimes, it’s just easier to type or say than a surname in a name-a-second radio spot — evidence “the Greek” versus Chris Karamesines, which many people couldn’t spell let alone pronounce.

Nicknames back then were cool and often self-descriptive, like “T.V. Tommy” Ivo, who capitalized on his television fame, or Arnie "The Farmer" Beswick, a real-life third-generation farmer, or describing physical appearance: Frank “the Beard” Bradley; "The All-American Boy" Charlie Allen; and Mike Mitchell, "the World's Fastest Hippie.”

“Superman,” for Jim Nicoll remains one of my favorites. The story used to be that he got the nickname for walking away unscathed from hairy crashes, but we later learned it was tagged upon him after he whipped a handful of guys in a bar fight one night after the drags at Irwindale.

Sometimes nicknames boasted of their success ("Northwest Terror" Herm Petersen or the "Ridge Route Terrors" James Warren and Roger Coburn) or mechanical prowess ("Sneaky Pete" Robinson), or lack thereof ("Hand Grenade Harry” Hibler).

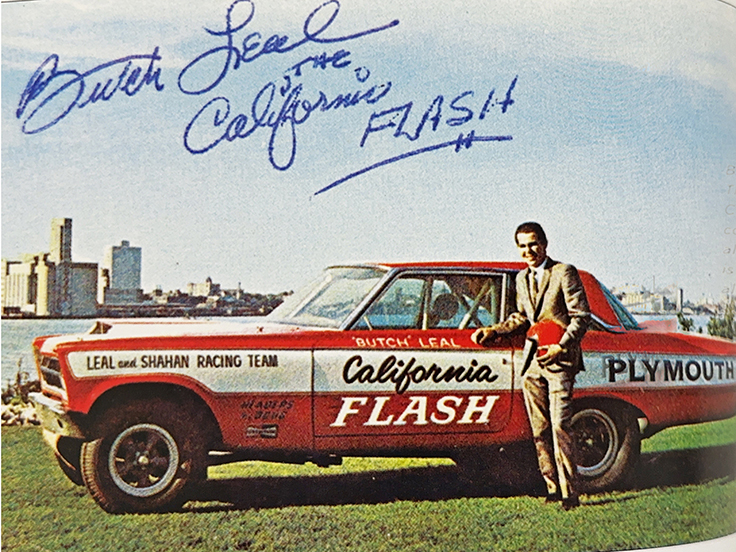

"Kansas John" Wiebe and “Ohio George” Montgomery got geographical nicknames as did "The DC Lip," early Funny Car pioneer Malcolm Durham, who was a notorious (and very adept) self-promoter. Another of my favorites is “The California Flash,” for Butch Leal, who got the name put on him in 1965 by the wife of his booking agent, Ben Crist.

Sometimes it was mannerisms, like "Gentleman Hank" Johnson or "Gentleman Joe" Schubeck or Bill "Grumpy" Jenkins, or lack of decorum (see "Jungle Jim" Liberman and John “Tarzan” Austin). Sometimes it was driving style: "Backdoor Bob" Struksnes or "the Moline Mad Man" Sid Seeley, for example.

There were those whose nicknames were plays on their names (Bennie “the Wizard” Osborn (thinkWizard of Oz) and Gene “the Snowman” Snow, or rhymes thereof — "Stormin' Norman" Weekly; “Starvin' Marvin" Schwartz; Gary “Blazin' “ Hazen; Roger “Dodger" Glenn, et al). "240 Gordie" Bonin got his nickname for his 240-mph Funny Car speeds and diminutive (in size only) flopper peer Tripp Shumake thus became "240 Shorty."

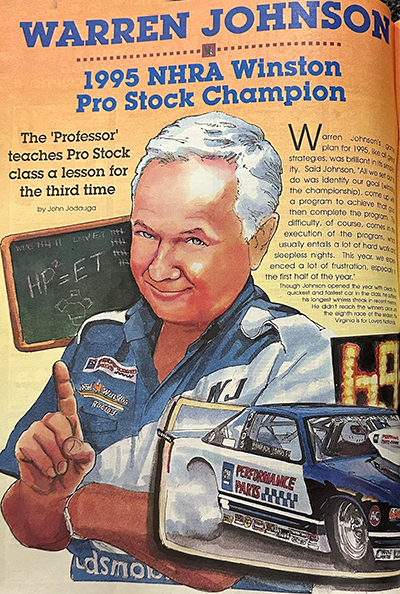

Anyway, all of that also got me to thinking of the dearth of current nicknames. Sure, Tony Schumacher is still (for some reason) “the Sarge” long after the Army deal ended (I think he was made an honorary sergeant or something when the deal was announced) but what was the last great modern-era driver nickname that stuck? Maybe “the Professor,” Warren Johnson? That’s a great one and very descriptive of his scientific approach to racing. Former NHRA National Dragster staffer John Brasseaux gets credit for the nickname, which was popularized in this 1995 championship profile and drawing by our old ND pal John Jodauga in National Dragster, but why didn’t Bob Glidden’s work-ethic-inspired “Mad Dog” ever stick? Why didn’t Lee Shepherd have a nickname? John Force used to be “Brute Force,” but I can’t remember the last time anyone used it.

I’m kinda partial to “Double-Oh” Dallas Glenn for the Pro Stock driver’s starting-line prowess, and I had a big hand in coining Sean Bellemeur-Steve Boggs-Tony Bartone power trio “the Killer Bs,” but there’s not many like that anymore.

Why doesn’t Justin Ashley have a nickname? Or Steve Torrence (beyond, of course, “Steve-o”). Or Ron Capps? Or Brittany Force? Or Erica Enders?

Years ago, the John Force Racing staff tried to push “Top Gun” on the world for its championship trapshooting driver Robert Hight, but it was off target and never registered a hit. Spencer Massey’s PR team came up with a contest for his nickname, but, fortunately, “The Bullet” was a dud. I think it was Alan Reinhart who nicknamed barrel-chested and grapefruit-armed Matt Hagan as “Hulk Hagan” as a riff on wrester Hulk Hogan, but he may be among the few who use it.

Open to any and all suggestions for any of the above or others.

Over the past couple of weeks, we lost a trio of well-known nitro racers: Gary Bolger, Clare Sanders, and Jim Brissette.

Over the past couple of weeks, we lost a trio of well-known nitro racers: Gary Bolger, Clare Sanders, and Jim Brissette.

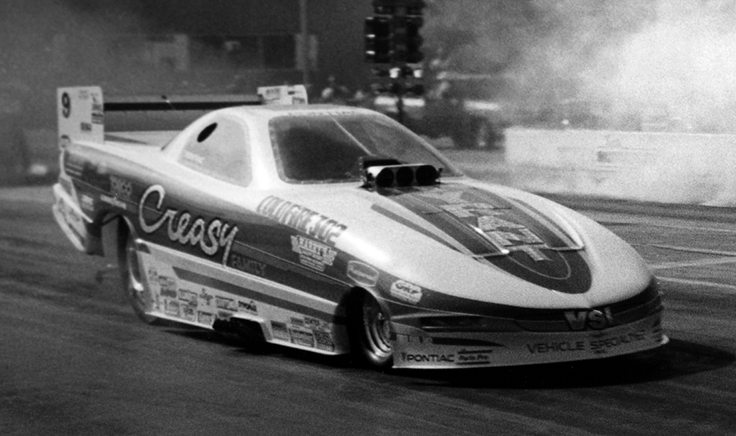

Bolger, who drove Funny Cars for more than 30 years on the NHRA circuit and logged three top 10 finishes and two national event runner-ups in the Creasy Family entry, died July 19. He was 79.

Bolger attended his first drag race in 1960 in Oswego, Ill., and not long after began racing stockers. When the Funny Car class came around in the mid-1960s, Bolger and partner Bud Richter were ready, fielding an A/FX Chevy II, first on gasoline and then later injected on nitro. He and Richter partnered on a number of cars before splitting up.

It was at a Coca-Cola Cavalcade of Stars event in the early 1970s when Bolger crossed paths with the Creasy family. Dick Bourgeois was the Creasy’s driver at the time and also raced his own car. At one race, he qualified for the final in both cars, and the Creasys, needing someone to drive their car, put Bolger in. He won the race and went on to become their full-time driver for more than a quarter-century before he relinquished the wheel to Dale Creasy Jr. in 1997.

Bolger logged NHRA top 10 finishes 1992-94, with that final year being his best as he scored runner-ups at the Englishtown and Dallas events behind Mark Oswald and Cruz Pedregon, respectively. Had not his throttle linkage broken against Oswald, he likely would have won that race as he was leading at the time.

Sanders, who drove “Jungle Jim” Liberman’s Chevy II to the Funny Car victory at the 1969 NHRA Winternationals, died recently at age 81.

It was a long road to the Pomona winner’s circle from Sanders’ childhood in Alaska, where his father was in civil service and the military. Sanders and early partner Jim St. Clair moved to San Jose, Calif., and the hotbed of Northern California racing in 1963-64. In 1965, they had their first Funny Car, dubbed Lime Fire, and the Barracuda was once called “The World’s Most Beautiful Funny Car."

The duo shared shop space with Funny Car pioneer Lew Arrington and his new driver, a kid named Russell James Liberman. Sanders went on to crew on Liberman’s car and began to drive his second team car in 1968. Liberman himself failed to qualify at the 1969 Winternationals and was able to apply his tuning talents to Sanders’ entry, leading to the win.

Later in the 1969 season, the team dynamics changed, and Sanders decided it was time to move on. He partnered in 1970 with New Orleans-based Frank Huff on the Chevy-powered Super Camaro (and, later, Super Vega) before being hired to drive the famed Chi-Town Hustler in 1971 and for the Ramchargers team in 1972. Sanders stopped driving after that season and went to work for Snap-on Tools driving a truck and in a 30-year career worked his way into management and sales.

To read more about Sanders' career, enjoy this 2016 profile I wrote about Sanders.

Brissette, who for more than 40 years was one of the best nitro tuners in the sport, died July 13. He was 81.

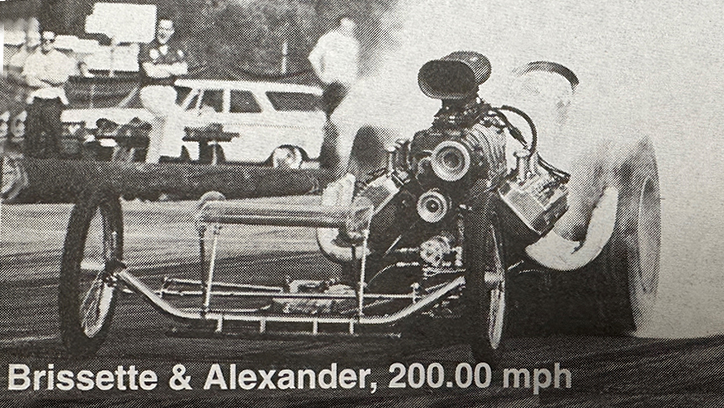

Brissette, who called on experience on dry lakes, got his first lead role tuning the Quincy Automotive dragster of Everett “Hippo” Brammer and “Wild Bill” Alexander in 1963. He raced successfully through the ‘60s with Alexander and Paul Sutherland before taking a step back. He returned in the early 1970s to crew for Bob Noice and later for Kelly Brown, and won the world championship with Brown in 1978.

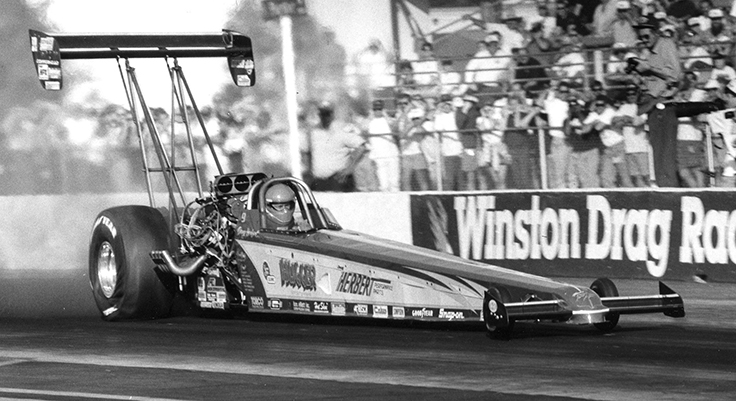

Brissette won a second world championship with Joe Amato in 1992 and also tuned for Tommy Johnson Jr. into the four-second club and Doug Herbert into the 300-mph club, among many.

"Jim was a great guy, and I learned so much from him," Herbert told me earlier this week. "I actually was introduced to him by my dad [Chet], who sponsored Jim back in the '60s and was my dad's favorite 'Chrysler guy.' Jim’s innovative ideas and aggressive approach to racing still has links to many of the parts run on current cars. More than my crew chief, Jim Brissette was my friend and a great family friend for decades."

Brissette was the first crew chief for today's hottest crew chief, David Grubnic, back when "Grubby" was driving John Mitchell's Montana Express Top Fueler, and it was with them that Gribnic earned his first top 10 finish, in 2000.

"That was in the early, in my early days " Grubnic reminisced with me earlier this week. "At the time, I mainly was contributing analysis work on spreadsheets, and I remember having a conversation with Jimmy saying, 'Here's what the numbers say we should do, and here's how the scenario should play out.' And I remember him looking at me and saying, 'I don't give a rat's ass what those numbers say. This is how it works in the real world.' And he was 100% correct, and it was one of those valuable lessons I learned from him. You have to balance the theoretical side of how all this works versus the practical side, and it's difficult to model that because of the forces that are involved. Jimmy definitely had the practical experience plus he understood the theoretical side of it. He had both, and he was definitely a great influence on me, and I respected him a lot.

"It's a great loss, like many of the other great innovators we've had. Jimmy was definitely one of them. My best goes out to Carol, his wife, his family, everybody, I was very fortunate to meet a lot of his family. He'll be deeply missed."

Among Brissette’s accomplishments is a rare one as he was the tuner for both the first 200- and first 300-mph runs at the Pomona racetrack, feats accomplished nearly 30 years apart. On Nov. 8, 1964, he wrenched Alexander (above) to a speed of 200.00, and at the 1993 Winternationals, he tuned Herbert’s Top Fueler to a speed of 301.60 mph, making Herbert (below) just the second driver to reach 300 mph.

When we interviewed Brissette way back in 1994, this was his personal list of top 10 achievements:

1. Doug Herbert's 1993 Springnationals win

2. Herbert's 301.60-mph run at the 1993 Winternationals

3. Joe Amato's 1992 Winston Championship

4. Tommy Johnson's Cragar Four-Second Club

5. Paul Sutherland's 219.51-mph run in 1965

6. Sutherland's win at the 1965 AHRA World Championships

7. Bill Alexander's 202.24-mph run at San Fernando in 1964

8. Kelly Brown's 1978 world championship

9. Brown's record-tying four national -event wins in 1978

10. Bob Noice's 1979 Winternationals win, which gave Brissette back-to-back Winternationals wins (Brown won in 1978)

Man, that’s an impressive list!

OK, race fans, that's my weekly roundup of new stuff. I'm off to see my mom in Oregon (I'll tell her you said hi), and then it's Topeka and Brainerd back-to-back, then off to Indy. Somewhere in there, I'll have another column, so stay tuned, and, as always, thanks for reading.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator