Ontario Motor Speedway

|

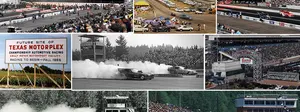

Last week’s column about Funny Car elapsed times and the number of class-best passes that were recorded on the quarter-mile at Ontario Motor Speedway, along with what we have learned over the years about the track’s ability to dish out big numbers in Top Fuel, like Mike Snively’s barrier-breaking 5.97, Don Moody’s 5.91 in 1972, Don Garlits’ otherworldly 5.63, 250-mph pass, and the first all-five-second Top Fuel field in 1975, got me to wanting to learn more about the track and its history, so I delved into the history books and archives to find out some nuggets about what became a very hallowed quarter-mile. I’ll talk about the history of the track itself this week, then look back at the incredible NHRA events at the facility next week.The idea of a Southern California superspeedway was proposed as early as 1956, with the thought being not only to create "the Indianapolis of the West," as it was hyped, but to create the crown jewel of racetracks with a supporting infrastructure and motorsports-driven economy. Developers envisioned a surrounding complex of race shops and specialty fabricators, plus restaurants and hotels.

Although the 2.5-mile oval track itself was modeled after the famed Indianapolis Motor Speedway, it was one lane wider and had banked short chutes between turns 1-2 and 3-4, which would make OMS slightly faster. And to live up to the “motor speedway” name, developers also planned for a 3.2-mile infield road course and a dragstrip that ran down the oval track's pit lane.

After a few failed starts, a location was chosen that seemed perfect: Ontario, just 50 miles from Los Angeles, with an 800-acre plot right on Interstate 10 (one of the nation’s main east-thoroughfares), and just across the highway from Ontario International Airport.

Ontario city fathers sold more than $25 million (that’s about $165 million in 2015 dollars) in municipal bonds to raise the capital for construction. The facility would then be leased to a group of operators who would run it on a day-to-day basis. A key factor that helped secure the green flag on construction was a signaled interest by the four major motorsports players — Formula 1, NASCAR, USAC, and, of course, NHRA — in holding events at the venue should it ever be built.

Ground was broken in late September 1968, and the track opened less than two years later, in August 1970, hosting a Celebrity Pro-Am Race, which featured stars from the entertainment industry paired with professional drivers. The race was later aired as a TV special on NBC.

The trademark five-story concourse housed a restaurant, bar, VIP suites, media center, and more.

|

The place lived up to its plush billing, especially in spectator amenities, the most obvious of which was the five-story suite complex that overlooked the start-finish line. (The original layout for the dragstrip was actually a few hundred feet further down pit road than it ended up, but a late decision was made to have the quarter-mile finish line match the win stripe of the oval course, which lined it up exactly in front of the huge concourse.)

On its first floor was a full restaurant, bar, and banquet hall, and the second floor featured VIP suites. Spectator seating took up where the third floor was, while above that was a deluxe, air-conditioned media center with the latest electronic gizmos (telecopiers and fax machines — oh my!). The fifth floor was dedicated to race control and also housed the 33 IBM computers that would track the 33 individual “Indy” cars that made up the starting field for the track’s first big race, the USAC California 500 event, and showed their positions on the track to spectators in real time during the race via a tall vertical scoreboard. This timing and scoring system was subsequently adopted by the Formula 1 circuit and ultimately by Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

In the pits, 50 enclosed garages were built to accommodate teams, and permanent facilities also were incorporated for tire manufacturers. Racers also had their own restaurant and meeting room in the pits. For the drag racers, roller starters were added to light the nitro cars.

Enclosed garage spaces for 50 cars provided a luxury to drag race teams not known in those days.

|

|

Roller starters offered teams another luxury.

|

The first six months of operation did indeed feature racing from all four major sanctioning bodies, hosting the California 500 (Sept. 6, 1970), Mattel Hot Wheels NHRA Supernationals (Nov. 21-22, 1970), Miller High Life 500 NASCAR race (Feb. 28, 1971), and Questor Grand Prix (March 28, 1971), and each of them drew attendance second only to their established counterparts: the Indianapolis 500, U.S. Nationals, Daytona 500, and U.S. Formula 1 race at Watkins Glen. The 178,000 in paid attendance and $3.3 million gross from the inaugural California 500 remained the largest crowd and highest gross in inflation-adjusted dollars of any single-day sporting event other than the Indianapolis 500 for nearly three decades.

Although the NHRA events — the Supernationals and the World Finals (when it was moved there in 1974) — always drew well (because their action was limited to the home straightaway, seat-selling options were limited), later editions of the oval-course events never came close to filling the 155,000 spectator seats, or even the 100,000 necessary to break even. In its first six years of operation, the place was shut down twice because the track operators couldn’t pay out the $1 million in bond interest each year.

|

Then the track operators got creative, opening their doors for other spectacles. On the day before the February 1971 NASCAR race, they booked in Evel Knievel to jump over 19 cars — the jump was filmed as the climactic scene for the eponymous movie starring George Hamilton — and 50,000 people showed up. (Knievel successfully landed the jump and set a record that stood for 27 years until Bubba Blackwell jumped 20 cars in 1998.)

The California Jam rock festival concert was held April 6, 1974, and drew a crowd of 300,000-400,000 fans — at the time the largest paid attendance for a rock concert — to see the Eagles; Deep Purple; Emerson, Lake & Palmer; Rare Earth; Earth, Wind & Fire; Seals and Crofts; Black Oak Arkansas; and Black Sabbath. Portions of the concert were televised live on ABC. California Jam II was held March 18, 1978, and drew almost 300,000 to see Ted Nugent, Aerosmith, Santana, Dave Mason, Foreigner, Heart, Bob Welch, Stevie Nicks and Mick Fleetwood, Frank Marino and Mahogany Rush, and Rubicon.

In 1974, Parnelli Jones and the Hulman family, which owned Indianapolis Motor Speedway, were brought in and restored some semblance of order to the racing side of business, but the track always seemed to be living on borrowed time.

That time ran out in late 1980, just after the running of 1980 NHRA World Finals. Land values had soared — from an average price of $7,500 per acre in 1969 to $150,000 per acre — and Chevron Land Company, a division of Chevron Oil, seized the opportunity to take advantage of the speedway’s failing fortunes. They purchased the facility for approximately $10 million (the estimated commercial real estate development value was $120 million) and demolished the track the following year at a cost of $3 million.

|

The property remained vacant for several years before Hilton built a hotel on about where Turn 4 was, and development has slowly grown over the years to take up over half of the speedway's footprint with condominiums, business offices, retail stores, and the Citizens Business Bank Arena, home to the AHL Ontario Reign (minor-league team to the L.A. Kings), which was built in the general area of Turn 3. Contrary to speculation, the Ontario Mills Mall is not built on part of the old racetrack; it’s on the east side of Milliken Avenue, which was the eastern border of the track.

The legacy of the track does live on in several places, most notably the automotive-themed street names: Jaguar Way, Corvette Drive, Triumph Lane, Shelby Street, Concours Street, Lotus Avenue, Porsche Way, Mercedes Lane, Duesenberg Drive, and Ferrari Lane.

The City of Ontario built racing-themed Ontario Motor Speedway Park a few blocks west of the racetrack site (near the intersection of North Center Avenue and Concours Street), and in 1990 the Ontario Center School, located on what was once the west parking lot for the racetrack, was dedicated to the premise of "Winning Through Education." A circular central hall, similar to the racetrack, was built, and speedway graphics, including the familiar OMS logo, were used in the classrooms. The kindergarten area has green flags on its walls, signifying the start of the educational race. And the sixth-grade area is adorned with checkered flags, the finish line. Three flagpoles in front of the school were from the speedway.

In a way, the dragstrip continues to live on just down the freeway in Pomona. The iconic dragstrip timing tower that manned the starting line at OMS was saved and transplanted to Auto Club Raceway at Pomona, where it was placed behind the starting line and served as race control for a number of years until the current tower was built. Today, the tower stands sentinel in the parking lot and serves as a command post and lookout for facility security.

Ontario Motor Speedway may be gone, but it’s remembered by the city, and especially by hard-core race fans like us who remember its dragstrip as the place where records were set, history was made, and the nationals were truly super.

The OMS track, overlayed on a current Ontario street map, courtesy of InsideTheIE.com. (view bigger)

|