Leroy 'Doc' Hales: World's fastest doctor

WDIFL.com

|

In my early years here at NHRA, in the early 1980s, a lot of the staff spoke reverently of Leroy “Doc” Hales, a former Funny Car racer who had joined the NHRA team after his career and became an integral member of the NHRA Safety Safari in the 1970s and early 1980s. Hales left NHRA just as I arrived, and although I had written about him infrequently (he was most recently mentioned during the topless Funny Car thread), our paths had never crossed until Bernie Partridge’s memorial service earlier this year, a function that the good doctor led eloquently from the podium.

After the service, I introduced myself, told him of my interest in sharing his story, tucked his business card in my pocket, and made a promise to touch base soon. The current Funny-Cars-on-fire thread became “soon” enough.

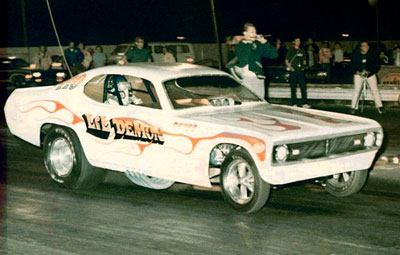

To answer the most obvious question, yes, Hales was a real doctor – specializing in emergency medical treatment -- and one who put himself through medical school in part thanks to his employment as a Funny Car driver. Hales is best remembered as the longtime driver for Pete Everett in a series of cars that culminated in the Pete’s Lil Demon entries in which he suffered severe burns that ultimately led to his retirement from driving and all of which made him a reliable and compassionate expert when it came to dealing with NHRA drivers in peril.

Steve Reyes

|

|

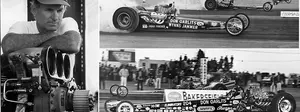

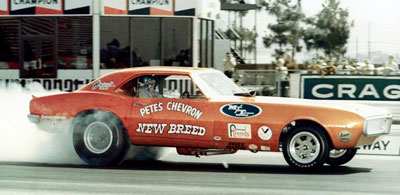

"Doc" Hales' first floppers, from top: the first Half-Breed topless Funny Car; the New Breed Firebird; and the ex-Dee Keaton Cougar, Wild Breed

|

Hales came to drive for Everett through his friendship with Everett’s son, Bill, who was a few years ahead of him at Southern California’s Montebello High School. The Everetts had a ’62 Plymouth with a 413 wedge that they raced in Super Stock and, with injection, in B/Gas; the younger Everett got drafted to Vietnam in 1965, and Hales eventually took over the driving chores of the car that later became known as Half-Breed because it had a '62 Plymouth back half and a ’65 Dodge front clip with a late-model supercharged Chrysler Hemi for power.

“The Half-Breed was our first venture into the world of Funny Cars, which was evolving, but it was a very poor attempt at it,” Hales remembered. “We didn't race that version very long. It was a real monstrosity. The car went to the scrap heap, but in 1967 or ’68, Pete traded the engine to Marv Eldridge of Fiberglass Trends for a complete Pontiac Firebird Funny Car – it was a fiberglass body where the hood folded forward and the doors actually opened –powered by an old-style supercharged Chrysler Hemi and a Torqueflite transmission that I consider my first Funny Car. That was the car called New Breed. We had moderate success with that car, then sold it, and Pete bought Dee Keaton's Mercury Cougar flip-top Funny Car.”

After enjoying success locally in Southern California, Everett and Hales were contracted to perform in Hawaii and shipped the car to the islands, where they raced – and beat – every good car in the state, including Top Fuelers, then sold the car to a local racer and came home empty-handed.

Their next car was the first Funny Car constructed by dragster expert Don Long – Long was simultaneously building a chassis jig for Funny Cars as he built their car with the idea of being able to quickly build any single part and ship it to touring racers in trouble back East — and that became the first Pete’s Lil Demon.

During this time, Hales was still in medical school. He had attended USC as an undergrad and would eventually earn his degree at the University of California-Irvine medical school in June 1971 – he was in the first medical school class to graduate there – and serve his internship at Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center in June 1972, but his whole life almost changed in mid-May 1971 at a Division 7 points meet at Irwindale Raceway.

At this 1971 Irwindale (Calif.) divisional event, Hales had a catastrophic fire in the Pete's Lil Demon entry that left him with a badly burned right hand.

|

Racing Mike Halloran in round one, Hales set low e.t. of the meet with a 6.96 at 210.28 mph, but all hell broke loose after the finish line.

“Crowerglide clutches were new, and everyone was trying to figure out how to get them to work,” he remembered. “We finally figured it out, but the car shook like it had never shook before, but I knew it was on a pass. I knew it was going to run real well, but it had shaken so hard that it shook out the front crankshaft seal; at that time, there were no lips to hold it in like you have today.

“The instant I lifted, all of the oil ran out of the front of the engine and onto the red-hot headers, and – boom! – it went up in flames, and I was sitting in the middle of this huge ball of fire. I reached down and pulled the fire bottles, and it quenched it to the extent that it went way down – the flames pulled away from me and back to the front of the car – but when the bottles ran out – after like three or four seconds – it erupted back on me again."

Part of the problem was the small extinguisher payload, the other was that teams were still working the bugs out of how best to use them.

Hales, suited up and ready to run in typical early-1970s Funny Car gear

|

“The problem back then was what size nozzles to use and where to put them, and it was really by-guess-and-by-golly. It was, ‘Here’s what I think is going to happen if the car catches on fire, so probably we ought to put nozzles here,’ and refilling the Freon bottles was expensive, too, so no one tested the system until you actually used it. We all gave it serious thought, but there were no specifications beyond ‘You had to have five pounds,’ and we actually ran two five-pound bottles.

“We had decent firesuits – I think they were three- or four-layer suits – made of Nomex, and we wore the Nomex underwear. We wore the aluminized face masks with breathers and goggles and open-face helmets with head socks. We had fire boots. Everything was state of the art except for my gloves. Back then, we didn’t realize how important that was. Our gloves were single-layer aluminized on the top and leather on the palm.

“The first thing the fire did was vaporize the parachutes, so I pulled on the hand brake – and at the time, we only had rear brakes, not four-wheel brakes like they have today – but it just happened that fire was coming into the cockpit right at that point where I had the brake fully pulled back.

“My hand was burning up and hurting like crazy, but I know I can’t let go of the brake because the chutes are gone and this is the only way I can stop the car. I remember thinking, ‘I’m going to die, and I hope this doesn’t take too long because this really hurts.’

“The fire eventually blew out the rear tires, and the car skidded to a stop. Once the car stopped, the fire was no longer being blown back onto me, so I unbuckled and rolled out the window. We didn’t have escape hatches yet, but there were no windows yet, either. I rolled around on the ground to make sure there was no fire on me.”

Hales suffered second- and third-degree burns to his hand – not a good turn of events for a doctor – and actually finished his surgical rotation with a bandaged and severely injured hand. Despite the peril, Hales returned to the cockpit and drove for another year.

“In June 1972, I finally decided, ‘This is not a prudent thing for a physician in emergency medicine to do.’ I got away with it once without any permanent damage, but I didn’t know if I could get away with it again. It was a painful decision because I loved driving Funny Cars so much.”

Hales didn’t stay inactive long. It was through industry mover and shaker Holly Hedrich – then employed at Keith Black’s, where the Everett team bought its engine blocks -- that NHRA’s Jack Hart heard of Hales’ history and expertise. With his specialty in emergency medicine -- and the fact that UC Irvine’s burn center was the preeminent burn center at the time -- and his racing background, he was a perfect fit at a time when NHRA was ramping up its safety efforts with the reformation of the Safety Safari and exploring new technologies to make the sport more safe.

(Above) In the early 1970s, NHRA began to organize what is now known as the world-famous NHRASafety Safari presented by AAA. The TRW Safety Caravan (above) used a lot of borrowed equipment and not much specialty equipment. (Below) With financial support from Weber, things really improved in 1974. From left are Funny Car hero Don Prudhomme, future NHRA Vice President and then Safety Safari volunteer Cary Menard, and Safari coordinator "Diamond Jim" Annin.

|

|

The Safety Safari – which in the 1950s had been an operational-type group dedicated to establishing racetracks and organizing races and not the legendary emergency-reaction team for which it’s now renowned – actually had laid fallow throughout the 1960s until the early 1970s.

“Throughout the 1960s, there was no Safety Safari as we know it today,” said Steve Gibbs, NHRA’s longtime competition director.

“Everything we needed at a race, from trucks to brooms, we had to scrounge up locally. There just weren’t enough events then – only about a handful – to have dedicated equipment to travel the country or even full-time people. A lot of us did a lot of different jobs, and we did a great job, but as time went on, it evolved.”

“There was no caravan of vehicles,” remembered Hales. “I think we had one pickup truck, and everything else came from the local dragstrip. We started almost from scratch, looking at the firesuits and ways to extricate drivers from the cars -- we came up with epaulets on the shoulders of the firesuits to have a handle to get someone out of a car once we’d cut the cage off – and even, ‘What do we use to put the fires out?’ We experimented a lot and discovered that if we put dishwashing soap in the water, it would break the surface tension of the water and would stick wherever we shot it.”

In 1972, there was a rudimentary effort – called the TRW Safety Caravan – with a few vehicles, but in 1974, Weber Performance provided sponsorship to purchase more equipment, and Hurst donated one of its famous Jaws of Life tools. Gibbs and former Top Fuel owner “Diamond Jim” Annin led the charge, and Hales was a valuable addition.

“We just kept adding equipment as we went along, but the one thing we lacked was consistent medical attention,” added Gibbs. “We could find doctors, but we never had much luck with standby physicians. Their heart just wasn’t into it, and some were just there to make some extra money. 'Doc' was different. With his unique background, he was the perfect guy. That was a major step for us and set the standard for the excellent medical care we provide today.”

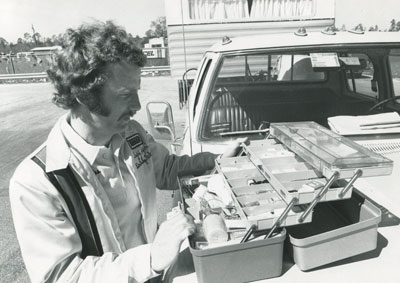

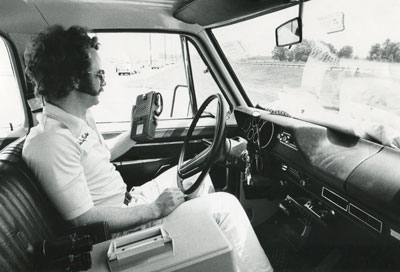

With medical kit and radio always at the ready, Hales took care of his NHRA patients for more than a decade as a valued member of the Safety Safari.

|

|

“I took care of a lot of our people,” said Hales proudly. “I took Shirley [Muldowney] to the hospital when she was in her Funny Car fire at Indy [1973] and helped so many people. We did a lot of good. Our main responsibility was getting the driver safely out of the car without inflicting any further damage and getting them to the hospital ER, which was equipped much better than we are. I would ride in the ambulance if needed to treat them along the way.”

Hales was the NHRA’s only physician for a decade and attended nearly every event in that span. Although his title was NHRA medical director, he was never an employee and never asked for payment of any kind beyond travel and room-and-board expenses.

“Basically, I was an unpaid, highly skilled NHRA volunteer worker, as most were in those days,” he said. “It was basically my vacation and cost me money to do it because I could have been earning a lot of money working an ER shift, but I loved the sport. We had a good time at the track and away from the track, too. The camaraderie was wonderful.”

Hales' accomplishments in the medical community away from drag racing at the time also were especially significant. He was instrumental in having emergency treatment become a board-certified specialty in 1979 and started, from the ground up, one of the first paramedic programs in the nation.

After leaving NHRA and retiring from his medical practice, a very unexpected and unpleasant encounter with the criminal justice system inspired Hales to get a degree in law in 1996, and he devoted himself to helping those struggling in the legal system when he created Justice for the Incarcerated.

“I decided that there were a lot of people who were not getting fair treatment by our criminal justice system,” he said. “When I discover a case like that, I do the litigation to get them unconvicted or out on parole. It’s very gratifying work. Nationwide, we’ve released several hundred people from death rows because DNA evidence has subsequently shown they were not the perpetrator."

At one time, Hales also was a deacon in his nondenominational church and a volunteer chaplain for Racers For Christ. He also earned an Adult Ministry certificate from Moody Bible Institute in Chicago and today does work for an international prison ministry known as Kairos for men in prison in California.

As fulfilling as his life became after drag racing, he certainly looks back fondly on his time behind the wheel.

“It was exciting and a lot of fun,” he explained. "Back then, you could do it as a hobby – it was an expensive hobby – but you didn’t have to have mega corporate sponsorship to do it.

“I just loved it. To be a paid Funny Car driver in Southern California in the early 1970s? I mean, c’mon, it was a dream job.”