Front to back: The rear-engine transition

Last week’s column about John Wiebe, one of the last and best holdouts of the traditional slingshot Top Fuel design, and our other discussions of the 1971 and 1972 seasons got me to thinking about this tide-changing period in the life of Top Fuel.

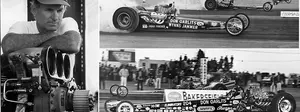

We all know that Don Garlits traditionally gets the lion’s share of credit for the rear-engine Top Fueler because it was he who perfected – at least in the national spotlight – the design and proved with his victory at the 1971 Winternationals that it worked.

The legend and imagery of that tale is just so great -- of Garlits, maimed by an explosion in his front-engine Swamp Rat 13 in March 1970, lying in his bed at Pacific Hospital in Long Beach, Calif., sketching designs for his game-changing next car, then winning in the car’s national event debut less than a year later – that it has become mythical in our sport and the accomplishment included almost anytime he is lauded.

Months after winning the Winternationals, John Mulligan died as the result of burns suffered in a fire at the Nationals over Labor Day weekend in 1969.

|

Don Garlits lost half of his right foot in this transmission explosion in Swamp Rat 13 at Lions Drag Strip March 8, 1970.

|

Jim Nicoll was lucky to walk away from a terrifying clutch explosion in his slingshot in the final round of the 1970 Nationals.

|

My respect for Garlits and all that he has accomplished and pioneered is off the charts, and, no doubt, Garlits, T.C. Lemons, and Connie Swingle deserve full credit for putting in the hard work of refining the concept -- I’d recommend you get your hands on the authoritative Don Garlits R.E.D. two-book set by Mickey Bryant and Todd Hutcheson -- and for changing the face of the sport through their success with the design, but even Garlits acknowledges in his book Don Garlits and His Cars that there were plenty of rear-engine cars before his. And even as we focus the thought to “modern-day Top Fuel dragster,” the Tampa gang was certainly the most successful but not the first by any stretch of the imagination. It has been pretty well-documented that there were at least a half-dozen “modern-day” predecessors to Garlits’ legendary machine, but we’ll get to all of that in a bit.

Like all of my “great ideas” for a column, this one quickly mushroomed out of control as my list of people whom I wanted/needed to interview grew from three to about 10 as new evidence continued to crop up. The story grew arms and legs and even fingers and became too much to jam in this week, so it will be a two-parter and include interviews with legendary chassis builders Woody Gilmore and Don Long and some of their earliest rear-engine customers (Jeb Allen and Carl Olson for Gilmore and Wes Cerny/Don Moody and Tommy Larkin for Long). Of course, I also needed to speak to Garlits and one of his first rear-engine customers, Tom McEwen.

All of that will come next week, but first, a little background that precedes Garlits’ historic victory in Pomona.

That a need existed for a new paradigm in Top Fuel was evident in the late 1960s. Although teams were still making performance improvements with the slingshot design – 1968’s widely recognized best e.t was 6.54, and by the end of 1969 (if you discount the wild 6-teens and 6.20s handed out like free popcorn in notoriously clock-happy Gary, Ind.), it had dropped to 6.43 – injuries and even death were a constant companion as engines, clutches, and bellhousings, pushed to and beyond their limits, began to give out with an alarming frequency, claiming heroes like Mike Sorokin. The aforementioned 6.43 was clocked by John Mulligan in qualifying No. 1 at the 1969 Nationals, but a disintegrating clutch in round one led to a terrible fire that ultimately claimed his life. Add in Garlits losing half of his right foot in the Lions transmission explosion and Jim Nicoll riding out his terrifying tumble alongside Don Prudhomme after a clutch explosion in the 1970 Nationals final, and you can see that it was a terrifying time to drive a fuel dragster.

(Keep in mind also that front-engine Indy cars had fallen out of favor -- the last one competed at the 1968 Indy 500 -- as the idea of safety and better directional stability and weight distribution became points of discussion.)

Tire technology had also caught up to drag racing, and the crowd-pleasing, quarter-mile rooster tails of tire smoke were quickly going away as the cars hooked better. The slingshot’s inherent advantage – having the driver weight over the rear tires for enhanced traction – now became a detraction, and the cars began to wheelstand more often, leading to the addition of up to 100 pounds of lead ballast on the front axle to keep the car earthbound. Changing the center of gravity would certainly help, and having the driver in front of the engine certainly was one way to accomplish that.

So, who had the first modern-day rear-engine Top Fuel dragster? It’s tough to say, but I do know that several of my past columns have uncovered multiple rear-engine Top Fuelers that predate Swamp Rat 14.

|

You may remember that in April 2010, I wrote about the STP Drag Wedge (above), which STP founder and Indy car entrepreneur Andy Granatelli commissioned from Dave Miller, who then worked at the Logghe Stamping Co. I don’t have an exact timeline of the car’s debut, but it was featured in the September 1969 issue of Hot Rod, which, with the traditional three-month lead time of the monthly magazines, means it was running as early as June 1969. I’m not by any means saying it was the first, but it’s an early entry for sure.

Gilmore had wanted to build a rear-engine Top Fueler for years before he finally achieved his dream in late 1969. Spurred by the death of Mulligan, a good friend and longtime customer, Gilmore and hired hand Pat Foster finally put together a rear-engine car that debuted in December with Leland Kolb’s engine for power.

“The year before, I had built a rear-engined Funny Car for Doug Thorley; I was really into Indy cars and Formula 1 at the time,” Gilmore recalled. “I took that inspiration and carried it into drag racing.”

Thorley’s Javelin, which had a 116-inch wheelbase, was lost in a crash at Irwindale Raceway in June 1969, and the same fate befell the Foster-driven dragster on one of its early runs at Lions Drag Strip.

Tom West was at Lions Drag Strip to capture these rare images of the Pat Foster-driven Woody Gilmore car just before it crashed. If you look hard at the photo below, you can see the troublesome "fifth wheel" behind the car.

|

|

|

In Gilmore’s mind, the reason for the crash is clear. At the insistence of Kolb and some others from his team who were afraid that the car was going to flip overbackward on launch, at the last minute, they installed a short tripod wheelie bar, with a single wheel just a few inches behind the rear axle and 4 inches off the ground. The car began to rock side to side and got up on the fifth wheel, which caused the car to tip onto one slick and go out of control. Possibly also contributing to the crash was the driveline setup, which was unique in that the engine was just 19 inches out from the inverted and reversed rear end (28 to 29 inches later became the norm).

In an interview on the We Did It For Love website, Foster recalled the experience.

“The first time out, at [Orange County Int’l Raceway] in December 1969, all went well until about half-track, at which time the car became very evil. We worked on slowing the steering ratio down [from 6:1 to 10:1] and went to Irwindale [Raceway] for more testing. It was better, but it still got very spooky at about 800 feet. After getting some new steering arms, the following weekend we arrived at ‘the Beach’ [Lions Drag Strip] full of confidence and ready to show the world the way of the future. She handled like a dream, on a string, moving hard the first half and settled in for a run to the eyes. About 50 feet before the first light, it went straight up, got up on a short single wheelie wheel, and cleared the right-side guardrail by five feet. I impacted a pole at 220 something [mph]. Myself and the front half of the car dropped to the bottom of the pole while the rear half with the engine went through the spectator parking lot and ended up almost on Willow Street.”

"I had about five orders for rear-engine cars at that time but they all canceled after Patty crashed," remembers Gilmore. "Everyone was skeptical about back-motored cars."

With lessons learned from that experiment, Gilmore and Foster built another for Dwane Ong, whose entry, named the Pawnbroker (for the 1964 movie of the same name), did remarkably well and should be considered the first truly successful rear-engine Top Fueler. (And yes, it’s Dwane, not Duane, as I and many others have erroneously written it throughout the years.)

I was thrilled to be able to track down Ong – he doesn’t use a computer or email, but a friend who runs a Facebook page for him gave me his number -- and get his memories of that time and that car, memories and details that remain very clear 45 years later.

(Above) Dwane Ong unveiled his Torque Pawnbroker at a trade show in Las Vegas in early 1970. (Below) Ong later added vertical stabilizers to the car.

(Photos from the Dwane Ong collection) |

|

Ong had been running a Gilmore-built front-engine car that he had purchased from the his Detroit neighbors on the Ramchargers team and had a new sponsor pending for 1970 with Hastings Manufacturing to promote its new product, Torque, an oil additive similar to STP. Late in 1969, he approached Gilmore about building him a new car.

“Woody asked me, ’Do you want to be a guinea pig?’ and he told me about the rear-engined car that he and Patty had built and were just about ready to test. He told me he thought the rear-engined car was going to be the future of Top Fuel. After the car crashed at ‘the Beach,’ Woody said he wanted to think things over for a few weeks to decide if he still wanted to go that route. Two days later, he called me back and told me he’d made his mind up and was going to build a new rear-engine car with or without me. I said I’d take it. Hastings liked the idea because they knew that if it worked, it would get them a lot more publicity.”

The car was delivered in time for Ong to run it at the March Meet in Bakersfield, and, like most of the early models, it did not have a rear wing, but at the suggestion of a friend of Gilmore’s, who was in the aerospace industry, Ong added two vertical stabilizers behind the engine in an attempt to counteract the car’s perceived tendency to rock side to side (thought to be the cause of the Foster crash). He doesn’t have any idea if they helped, but “We needed a place for decals anyway,” he said with a chuckle.

Ong reports that the car always went straight (“It was boring to drive; I almost didn’t have to steer it,” he said), but it hooked so hard that the clutch wore so badly, often wearing .150- to .200-inch off the discs on each run. Marv Rifchin, of M&H Tires, helped solve the problem by offering Ong narrower tires – 10 to 11 inches wide and mounted on 15-inch wheels (“They looked like Super Stock tires!” Ong remembered) versus 12-inch-wide tires on 16-inch wheels – that not only reduced the clutch wear to .030- to .035-inch per run, but, more important, also improved performance by more than two-tenths of a second.

Garlits, still months from making his first runs in his first rear-engine car, checked out Ong's ride in August 1970.

|

Bernie Schacker's self-built dragster was probably the first to run a rear wing.

|

These improvements helped him win the AHRA Nationals at New York National Speedway in late August. Garlits was at this race and, according to Ong, gave the car a thorough look-see, paying special interest to the front-steering setup and going as far as removing the nose of the car (with permission) to check it out. Garlits has publicly disputed the notion that he would ever ask anyone to remove body panels, but Garlits did confirm to me via email that he did ask for and receive permission to sit in the cockpit of Ong’s car. “I just sat in Dwane’s car for a few minutes, and the vision was unreal!” he responded. “I wondered right then what in the hell was wrong that these cars didn’t work and everybody have one!”

Ong, who by this time was running a Ramchargers-built powerplant, also claims that he was the first in the sixes and to exceed 200 mph in a rear-engine car in June. Around this time, East Coast veteran Bernie Schacker had a rear-engine car that also reportedly ran in the sixes in May but I wasn’t able to independently verify either of their claims.

(Update: Bret Kepner and a few others directed me to Drag News, Volume 15, Issue 47, which reports that Schacker ran 6.98, 192.70 to lose to Fred Forkner’s front-engine 6.92, 194.38 in the Top Fuel final round of New York National Speedway’s independent Spring Nationals. "Bernie was definitely the first under seven-flat [in a rear-engine car]," writes Kepner.)

Although Ong did run a few NHRA races – most notably just missing the Nationals field – he mostly campaigned on the AHRA circuit but only ran the car the one season before deciding to go back behind the engine in Funny Car after partnering with Ray Gallagher to run the Trader Ray flopper, also built by Gilmore. Ong did that for a couple of years and retired from racing after the 1974 season.

The Widner & Dollins rear-engine car, built by Mark Williams, also competed in 1970, with Dan Widner at the wheel. (Below) This car did not have a rear wing but included a small kicked-up section at the rear for downforce.

|

|

The other rear-engine car of real prominence that began running in 1970 was built by Mark Williams for Dan Widner and Mike Dollins. Williams began construction of the car in December 1969 and completed it in April 1970. The car, which cost just $2,111.16 to build, was the 59th chassis to come off of Williams’ jig. It was his first rear-engine car and had a lengthy wheelbase of 235 inches; typical front-engine cars of the era had 180-inch wheelbases, though some were longer.

“I had built front-engined cars for [Widner and Dollins], and we had talked about everyone getting oil and fire in their face; it wasn’t a very pleasant deal,” recalled Williams. “There had been other people who tried to build rear-engined cars, but they weren’t very successful because the wheelbase was too short. I felt that the wheelbase had to be longer for two reasons: to get the static weight distribution that you needed and to give the driver the same perspective he had with a front-engine car [relative to how far the front wheels were from the driver].”

Williams remembers that, despite the new design, the car tracked straight from the first hit and that the biggest problem that drivers faced was awareness of losing traction; they no longer could just glance sideways and see their slicks lit up in tire smoke or have a cockpit filled with smoke.

Williams remembered that Widner and Dollins did not run the car much due to financial reasons and that the car later came into the hands of the Colorado-based Kaiser brothers, who campaigned it with a degree of success though their efforts were no doubt hampered by their use of a budget-minded 354 Hemi instead of a 392. Despite proving that the concept could work, Williams built seven more slingshots before his next rear-engine car, which was built for Paul Gommi for the 1971 season.

According to Bryant and Hutcheson, even Garlits’ old partner, Art Malone, had run a rear-engine dragster before him, running one for six months in 1970 before dismissing it as “a fun project,” and the April 1971 issue of Drag Racing USA spotlighted the incredibly long (254-inch wheelbase!) rear-engine dragster of speed-shot maven Chuck Tanko, which was built by Frank Huszar’s Race Car Specialties shop in Southern California’s San Fernando Valley. Again, because of the lead time, this car probably was running (the article included a burnout photo) in January 1971, about the time that Garlits officially debuted his car. Ken Ellis, who built the car’s body, drove the car, which weighed a portly 1,375 pounds. The car, dubbed the National Speed Products Research entry, went 7.20s at 210 mph in its shakedown runs, but I can’t find any other mention of it after that.

So, as you can see, there were a lot of predecessors to Garlits’ car, though, with the exception of a few hits by the Kaisers, Ong, and Schacker, rear-engine cars were mostly misses, and Garlits does deservedly get the credit for proving – after much trial and error with the steering geometry -- the design’s worthiness.

Anyone who snickered – and there were quite a few – when Garlits unloaded his trailer at Lions for AHRA’s 1971 season-opening Grand American event Jan. 8-10 were at least partially silenced as he clocked a 6.60 – just .05-second off the track record – and went on to score runner-up honors behind “Mr. C,” Gary Cochran and his slingshot entry. A week later, Garlits was again runner-up, this time at the PDA event just down the 405 freeway at Orange County Intl Raceway and again to Cochran’s front-engine mount.

A few might have still believed that by Cochran holding down the front-engine fort that the rear-engine car’s day had still not arrived, but when “Big Daddy” mowed down the 32-car NHRA Winternationals field with precision, drove back east to win the IHRA Winternationals, then back west to win the fabled March Meet (which included an early-round win over Cochran), well, there wasn’t much for most of the remaining detractors to say except “How soon can I get one?”

As you’ll see next week, the answer was “not long,” but probably still longer than many had hoped. [Part 2]