Remembering Doug Kerhulas and Dave Hough

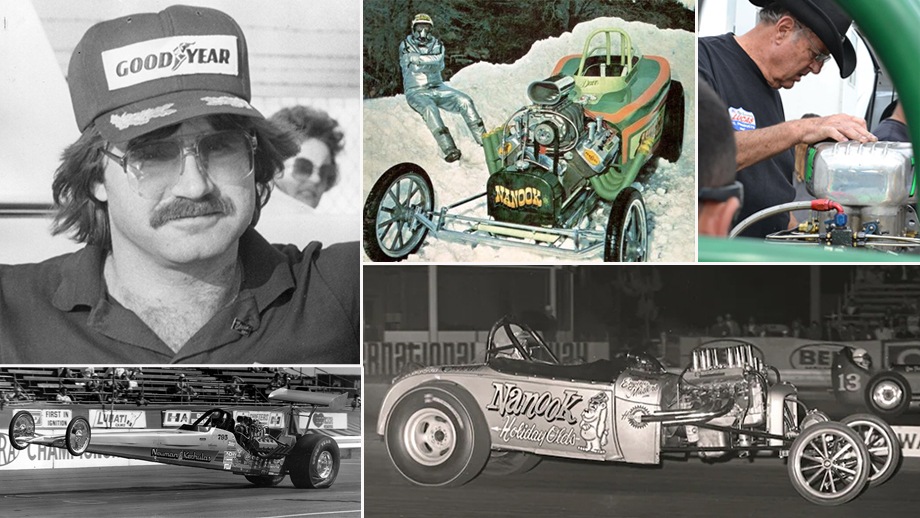

It’s been a sad parade of losses in the sport here lately, but two recent ones struck deep nerves with me as we lost 1980s Top Fuel star Doug Kerhulas and Fuel Altered icon Dave Hough in the span of 10 days.

As a young fan in the 1970s in Southern California, I saw a lot of Hough and his famed Nanook Fuel Altered, and even though he continued to be involved in racing until his passing last week, first with his son, Rick, and now grandson Kyle driving, I never had the pleasure to meet him.

Kerhulas, on the other hand, was a little-known Pro Comp racer in the 1970s before switching to Top Fuel in the late 1970s and was one of the first people I met at National Dragster in 1982 and someone I greatly liked and enjoyed being around for the short time he raced before a summer 1984 accident pretty much ended his driving career.

There was a lot of like about Kerhulas. Under a wild mop of hair and friendly eyes peering at you through glasses was an ever-present smile. He was always funny — some people nicknamed him “screwloose” (a rough rhyming to his last name) — and he almost always seemed to be having the best time no matter what.

Like a lot of racers in the 1970s, he dabbled first in street racing, wheeling his Chevelle around the streets of his Bakersfield hometown. But Kerhulas also was a top-flight baseball player who earned a college scholarship after he graduated from high school in 1970 and may someday have made it to the big leagues until he broke his right knee in a skiing accident.

Baseball’s loss was drag racing’s gain as he poured his energy into the quarter-mile, but it wasn’t always easy.

His first serious race car was a SS/EA Chevelle in 1970. “That car was a real dog," he told National Dragster back in 1979. "It ran 12.17 on an 11.78 record, so in '72 I built a B/Gas Camaro — another dog. That car went 10.17 on a 9.76 record. In 1974, I made a real mistake though and built a Vega Pro Stocker. The record was 8.97, and I was hitting 9.80s — what a joke."

Kerhulas, always looking for the bright spot, said that even though cars were dogs, their short wheelbases taught him a lot about driving and how to react more quickly.

When Pro Comp was formed in 1974, he quickly joined the class and found his first real success in 1976, when he came within one round of being the world champion, back when the champion was still decided by who won the World Finals.

By this time, Kerhulas had become friends with his Bakersfield idols, James Warren and Roger Coburn, who gave him driving and tuning advice, respectively, and he also worked on the Ridge Route Terrors’ cars.

"I fell in love with the whole dragster bit,” he remembered. “They push started then, and I'd ride on the push truck and get my mouth full of nitro. I loved it."

Kerhulas’ Pro Comp car, built by Ken Cox, ran a steel Chevy and was the fastest of its breed and carried him to a big WCS win at Fremont Dragstrip and to third in Division 7, which helped him reach that final at Ontario Motor Speedway, where he took on Brent Bramley.

"I really screwed up in the final,” he said. “I had gone 6.80 to qualify sixth and then went all the way to the final against Brent Bramley. The car shook off the line, but instead of getting out of it, I accidentally hit the kill switch and watched Bramley blow a motor and coast to the world title. There I sat without a chance to get going and pass him.”

Buoyed by that success and his friendship with Warren and Coburn, Kerhulas decided to make the plunge into Top Fuel in 1978, even as he and his wife, Barbara, were expecting their first daughter, Jaclyn.

"I had told my wife when I went Pro Comp racing that was it. I was having so much fun I didn't need anything else,” he said. “When I told her about the Top Fuel car in mid-'77, she looked at me like I was a real liar. Then I told her that I would do that for only one year, and we had a good season and won the Division 7 Top Fuel title.”

Kerhulas and his lone young crewmember Kirk Peters got a lot of tuning advice along the way from Warren and Coburn, as well as from Ed Pink and Don Prudhomme, and dramatically clinched the title at the season finale in Fremont. He beat one of his points rivals, Dave Uyehara, in the semifinals on a holeshot then locked up the title when Garth Widdison's starter failed, giving Kerhulas a single and the points he needed to outlast Uyehara and Rick Ramsey for the title.

Winning the same title that Warren and Coburn had owned for so many years, it was going to be hard to quit, but Kerhulas tried.

“I was ready to put the car up for sale per my agreement, but Earl and Kevin Neuman called me and said that they’d provide me with some backing, so I ended up staying in Top Fuel racing,” he said.

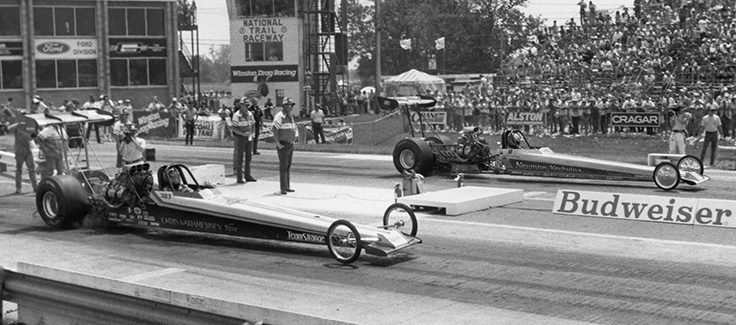

It took five years of hard work before Kerhulas reached his first NHRA national event Top Fuel final, at the 1983 NorthStar Nationals in Brainerd, where, after beating better-qualified Jody Smart and Larry Minor, he took on rising star Joe Amato.

Kerhulas, who had again won the Division 7 title in 1982, drilled Amato on the Tree, .440 to .563, and seemed well on his way to that first big win when a faulty water temperature gauge started leaking, shooting water into the injector, slowing Kerhulas to a 5.92 against Amato’s 5.75.

Less than a year later, on June 10, Kerhulas was having another monster event at the NHRA Springnationals in Columbus. He beat Al McFadyen in round one and the legendary "Golden Greek” Chris Karamesines in round two to set up a semifinal date with Gary Beck.

After a 247-mph run to beat “the Greek,” Kerhulas' rear wing collapsed and tangled up his parachute, and he ended up in the catch net. He suffered a closed head injury that required an extensive recovery. He was first hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit at Riverside Hospital in Columbus and in a coma for 10 days, so Minor used his private plane to fly Kerhulas’ family out to be with him, and Connie Kalitta provided the transport after he was released to care back home at Fresno Community Hospital in California.

A huge benefit was organized by the Miller family, then the owners of Famoso Dragstrip, and a huge turnout raised money for Kerhulas' recovery.

That summer of 1984 was a tough, tough time for Top Fuel, which was struggling for car counts and, in some people’s minds, on the verge of nearing extinction. IHRA even dropped the class from its national event competition in 1984 and didn’t bring it back until 1987.

Less than three weeks after Kerhulas’ accident robbed the sport of a rising star, three-time Shirley Muldowney had her infamous crash in Montreal on June 29. It was another terrible blow for the class, but it was “Big Daddy” Don Garlits' return to competition in Indy in 1984 — Muldowney told him to “Go up there and kick their asses,” and he did — and Charlie Allen’s booked-in match race at Firebird Int’l Raceway weeks later that resurrected the class and led to the creation of the Top Fuel Classic bonus event and the class’ return to prominence.

I spoke to Muldowney yesterday about her shared trauma with Kerhulas and their friendship in the years after.

“We were all very friendly even before that,” she said. “We would go fishing together, and he went to a Styx concert with us [when Muldowney had sponsorship from the rock band]. After our accidents, we talked weekly on the phone and stayed on a phone-call basis — me and Kenny Bernstein were always in touch with him — but life became very difficult for him, and we talked less. We had completely different kinds of injuries. I'm glad that he survived long enough to see his children grow up and move on to better things."

Muldowney then told me a hilarious story about an incident at the Breezy Point resort in Brainerd after she had won the 1982 NorthStars. Another patron got loud and aggressive with the Muldowney party at dinner, overturned their table, and brandished a knife, which led to an all-out brawl before Muldowney clocked him in the head with a glass ashtray. They beat feet out of there, loaded up their trailer, and headed out before the cops got there. Just as they were leaving, Kerhulas was pulling in after picking up a pizza, and the cops mistook one red trailer for another, dragged him out of his duallie, and put him facedown into his pizza on the hood of his truck until they realized they had the wrong guy.

“Doug never held that against us,” she said. “He was a good guy.”

Incredibly, Kerhulas (pictured here being welcomed back by then-NHRA paramedic Ronnie Davis, who had treated him on the scene in Columbus) was able to return to the dragstrip two years later, running at the 1986 Winternationals, but failed to qualify, then returned to the scene of the crash in Columbus. Though he failed to qualify there, too, he no doubt was proud to have faced down the memory of his accident. His final event came in Denver in 1987, where he also failed to make the show.

After racing, Kerhulas worked in contracting for various companies and with his father’s trucking company. In the last couple of years of his life, Kerhulas battled multiple sclerosis and passed away on March 1 at age 70.

I spoke to Kerhulas’ younger daughter, Jaime, last week, and she said he was still In love with racing until his passing.

“He was constantly talking about racing,” she remembered fondly. “Even when he developed dementia, he remembered me and my sister and my mom and racing. That was it. He still was telling the stories of racing to the very end. It was just crazy how that was the main thing that always stuck in his memory no matter what. My sister and I really never knew him in racing, and we always kind of growled at racing because of the tragedy it brought him, but we’ve been hearing so many nice things about him since his passing.

“I've gotten five messages from guys on his pit crew or their kids because they've passed away. It's interesting to see, even years and years later, that was still on people's minds. I'm getting just kind of that same overall vibe from everybody. It's been really nice.”

I asked if he continued his great sense of humor even after his accident.

“Oh, he carried that on no matter where we went to embarrass you,” she recalled with a laugh. “The things that would come out of his mouth … we'd go somewhere and he’d be like, ‘I'm knocked up. I'm pregnant’ … just random things to get like a laugh and smile out of people. He cracked me up.”

Us, too, Jaime. Even though we hadn’t seen a lot of him lately, he’ll be missed by so many.

While Kerhulas was near in our hearts while far from the track, Hough never left the dragstrip he first started frequenting in 1960, remaining part of his family’s racing team with his son and grandson through last season, helping son Rick tune the famed Nanook for young Kyle. Hough died on March 10. He was 79.

Hough’s first race car was a 348-powered ’59 El Camino that he first street-raced as a teenager. After a friend was involved in a fatal street-racing accident, Hough decided to move his thrills onto the dragstrip and raced the El Camino in 1960 and ’61 out of Les Ritchey’s Performance Associates stable. After he sold the car, he sat out for a few years before building the first Nanook altered, a carbureted Olds-powered, steel-bodied ’29 Ford roadster that ran 9.20s in A/Altered, with partner Ed Moore. [My old pal Dave Wallace wrote a tremendous story on Hough for Motor Trend, using Hough’s own words and some great photos, that you can find here.]

The fabled Nanook name — Eskimo for “polar bear” — had a funny origin. Moore’s girlfriend, Yvette, always used to wear a fur coat, and her nickname was Nanook, and that’s what ended up on the car.

The team switched the Olds from carbureted gas to injected alcohol, but In 1967, Hough and Moore borrowed a nitro-burning 392 from Charlie Brandt, who had crashed his Top Fueler, and Hough never looked back, beginning a career in racing and promoting Fuel Altereds that he would continue for the next 50-plus years.

Don Tuttle built them their first purpose-built Fuel Altered in late 1968, and with the help and guidance of Ed Donovan, the Nanook started tearing up the record books, starting with a 210-mph run at Irwindale Raceway that broke Pure Hell’s long-standing mark of 208 mph. By late 1969, Hough owned both ends of the track record at Irwindale, Lions Drag Strip, and Orange County Int’l Raceway.

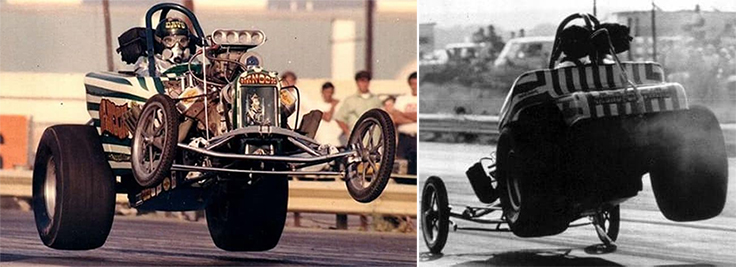

In 1970, Hough became just the first AA/FA driver to dip in the sixes, following on the heels of Leroy Chadderton, with a 6.96 blast at Fremont Dragstrip. A new Nanook, built by Dennis Watson with a lower, Funny Car-style chassis and a Crowerglide-equipped, 392-powered setup, made its debut at Lions’ Last Drag Race in December 1972 with a 6.92 at 213 mph and ran a best of 6.54 at 218 mph by the end of 1975.

In an era when Fuel Altereds were known for going every which way but straight, Hough and the Nanook reportedly completed 75% of their runs, which Hough credited to a spring-loaded Posi-Traction rear end that Donovan had suggested he try. Not that the Nanook was not prone to its wild runs as the memorable dual wheelie/nosestand sequence at Irwindale above will attest.

Hough was also a good sport when it came to magazine shoots, posing memorably with a Redondo Beach, Calif., policeman as he was being “ticketed” that ran on the cover of the September 1973 issue of Popular Hot Rodding, and then one in a freezing snowbank worthy of the Nanook name, a photo that ran in the cover of the April 1973 issue of Drag Racing USA.

Steve Reyes shot both of the photos and shared interesting stories of both with me in a column I wrote about those great 1970s drag racing magazine shoots.

“Dave Hough was wonderful to work with,” he recalled. “If I would have told him, ‘Hough, we’re having a shoot with the devil in hell,’ he would ask me what time he needed to be there. I had already shot the earlier Nanook among the cactus at the Saguaro National Park out near Tucson [Ariz.], and he had gotten some really nice exposure in a couple of magazines for that, so he was always ready to go.

“I got the idea to take the car to the snow; the whole Eskimo-Nanook thing in the snow, right? We trailered the car way up into the San Bernardino Mountains near Big Bear Lake and stopped when we found the first snow. We unloaded the car and pushed it into the snow, then built snow around it, then had to smooth out the footprints to make it look nice. I had him sit on the ice, and even though he was wearing a firesuit, he about froze his butt off; I don’t think he was wearing much under the suit."

The Nanook made more big headlines in 1976 when Harry Eberlin, owner of the Super Shops chain of high-performance stores and a high school friend of Hough and wife Linda, decided he was going to give away a race car as part of a promotion for his burgeoning business. It initially was going to be a Pro Stocker, but Hough convinced him to make it a Fuel Altered instead, leading to a massive “Win This Car” campaign (hence the new nickname “Super Nanook”) that was continued into 1976 when Hough was talked into driving a Jamie Sarte-built Plymouth Arrow Funny Car for nationwide attention at NHRA national events from which Fuel Altereds had been banned beginning in 1973.

“I didn’t like it compared [to] the Fuel Altered,” he told National Dragster in 1999. “I always liked seeing the engine flames, which would tell me if it was dropping a cylinder and things like that. With the Funny Car, when they lowered the body, it was like closing a lid on me. Everything got muffled.”

Hough ran the Funny Car in 1977, but Eberlin wanted Hough to quit his full-time job at the California Portland Cement Company to run the complete schedule. Hough, not wanting to lose his health and retirement benefits, refused after Eberlin wouldn’t give him a signed two-year contract.

Three-quarters of the year through the 1977 season, Hough was replaced in the car by Pat Foster, and Foster was replaced by Ed McCulloch in 1980.

In addition to racing, Hough was also making a ton of appearances at the openings of new Super Shops stores.

His son, Rick, told me, “I want to say Harry had nine or 10 stores when we started, and by the time we had the Funny Car, he had probably 30. He wanted my dad to step up and run the thing full time and make all the national events, and he was even willing to fly my dad in. My dad didn’t want to give up his retirement and had two kids in high school and a mortgage and didn’t see racing as a livelihood. In hindsight, if he knew what drag racing was gonna turn into, it probably would have been a better move.”

Hough and family moved to Hawaii in 1980 to take over a cement plant there. Hough built a Super Comp car for his son, Rick, that they raced for five or six years before Rick returned to the mainland.

Hough followed his son in 1996 and bought an industrial supply company in Las Vegas, but he never lost the racing bug. A visit to the 1998 National Hot Rod Reunion convinced him that maybe he should resurrect the Nanook.

He turned the wheel over to his son, Rick, in 1998, and Rick had his hands full, as he told me earlier this week.

“The car is just a handful,” he said. “I don't know whether we tried to make too much horsepower for the length of the car, or whatever. Sometimes it picked up and hauled right down the track, but the majority of the time the thing was just an animal to drive. We tried to win every race that car goes down the track. That was the way my dad was. He ran it the best that it would run every time it went down the track.

“He had a much better feel for the car than I ever did. I was all or nothing. I was a drive-it-until-I-couldn't-drive-it-any-further guy. He had a little more finesse than me. He would say, 'Oh, you should have grabbed a handful of brake, ' and I'm like, 'Are you kidding me? I can barely get the thing down the track, let alone grab the brake.' My son is better than me. He has a better feel for it, like his grandfather, than I did. But my dad was really, really good with me. He was never disappointed that I didn't get the car down the track. No matter what happened, he was always proud of the job I was doing in it.”

Rick drove the car for about eight years but had two nasty accidents, the first at Firebird Raceway in Boise, Idaho, in 2005 in which he broke his neck and was in a coma. They rebuilt the car, but he crashed again, at the 2006 NHRA Gatornationals after a career-best 6.16 pass. His right hand was mangled so badly in the accident that it was later amputated, ending his driving career.

“My son was like 12 or 13, and my dad just didn't want to stop racing, so we had my brother-in-law, Vince Generalao, drive the car for a couple of years. Jon Capps and Randy Baker and Steve Tryon also drove it a couple of times, but mostly, it was Vince, who did a good job for us, then Ron Marone drove it for a season until my son was ready.

“When my son turned 15, we sent him to Frank Hawley's [Drag Racing School], and Frank said, ‘You know, he probably ought to drive something before he drives that roadster,’ but my theory was, 'Hey, I want to put him in what he's gonna drive the rest of his life. I don't want him to give me [or] pick up any bad habits driving.'

"As soon as he got his driver’s permit, I started taking him off to the racetrack and started making some runs. When he turned 16, we took him to Bakersfield, and he went right down the track three times: 6.40, 6.30, and 6.20 on three runs. We started running IHRA national events, and he made probably 150 to 200 runs on the car in his first three years in it. His first full season was 2012 when he was 19, and he won the championship and also won at the 2016 Hot Rod Reunion.

“I was probably a little harder on him than my dad was on me. My father was so proud of his grandson. I was almost like the forgotten one,” he said with a laugh. “All the interviews and all that it was like, he went right to his grandson … didn't even mention me.

"I'm proud of my son, too. He did a pretty good job in the car. The only knock I have on Kyle is I was very, very sensitive to my money. When I was driving, any time the thing missed a beat or anything like that, I would take my foot out of it. My son has driven a little further than he should have a few times. He's fireballed it a couple of times. I have to keep reminding him that his foot's attached to my wallet.”

Dave Hough’s health began to decline in the last few months, but he was always eager to get back to the track.

“He ended up with lung disease from his work at the concrete plant for so many years and inhaling silica sand,” said his son. “He worked there back in the ‘60s before anybody cared about respirators and things like that, so he lost a lot of his lung capacity. The last eight or nine months, it just got out of control. One of the last races he went to was in Tucson at the end of last year. He ran Tucson so much that all the people that remembered him wanted to talk to him, but he was just getting tired too quickly.

“Even still, that race car was his whole life. That's what kept him alive. He wanted to talk about the race car and what we're doing, and to the very last week, he wanted to talk race cars.

“He was an absolute legend, and I hope people appreciate the fact that he kept Fuel Altered racing alive in the '70s and '80s. He literally had a group of 10 or 12 he took around and got bookings for. He was still booking races for the last year.”

In his final interview with National Dragster in 1999, Dave Hough reflected, “The racing days were the best times of my life. Every time I climbed into the car it became a heartstopper. I was glad that I could race at the time I did because it was a period where you could actually make money at it and have a lot of fun.”

His son and grandson plan to continue having fun and will move to Nostalgia Top Fuel this year with a car purchased from Butch Blair that they hope will be ready in time for the NHRA National Hot Rod Reunion.

The Hough name and reputation will live on through them for years to come, and we can all be happy about that.

Phil Burgess can be reached at pburgess@nhra.com

Hundreds of more articles like this can be found in the DRAGSTER INSIDER COLUMN ARCHIVE

Or try the Random Dragster Insider story generator